Iceland was supposed to be different.

In allowing its banks to fail, neo-Keynesian economists have argued, Iceland avoided the fate of Ireland, which nationalized its banks and now faces a future with a very large public debt. By devaluing its currency, the krónur, Iceland avoided the fate of countries like Estonia and others in southern Europe trapped in the eurozone and a one-size-fits all monetary policy, allowing for a rapid return to economic growth and rapidly falling unemployment. Neoclassical economists counter that Iceland’s currency controls mean that it’s still essentially shut out from foreign investment, and the accompanying inflation has eroded many of the gains of Iceland’s return to GDP growth and, besides, Iceland’s households are still struggling under mortgage and other debt instruments that are linked to inflation or denominated in foreign currencies.

But Iceland’s weekend parliamentary election shows that both schools of economic thought are right.

Elections are rarely won on the slogan, ‘it could have been worse.’ Just ask U.S. president Barack Obama, whose efforts to implement $800 billion in stimulus programs in his first term in office went barely mentioned in his 2012 reelection campaign.

Iceland, as it turns out, is hardly so different at all — and it’s now virtually a case study in an electoral pattern that’s become increasingly pronounced in Europe that began when the 2008 global financial crisis took hold, through the 2010 sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone and through the current European-wide recession that’s seen unemployment rise to the sharpest levels in decades.

Call it the European three-step.

In the first step, a center-right government, like the one led by Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn (Independence Party) in Iceland in 2008, took the blame for the initial crisis.

In the second step, a center-left government, like the one led by Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir and the Samfylkingin (Social Democratic Alliance) in Iceland, replaced it, only to find that it would be forced to implement harsh austerity measures, including budget cuts, tax increases and, in Iceland’s case, even more extreme measures, such as currency controls and inflation-inducing devaluations. That leads to further voter disenchantment, now with the center-left.

The third step is the return of the initial center-right party (or parties) to power, as the Independence Party and their traditional allies, the Framsóknarflokkurinn (Progressive Party) will do following Iceland’s latest election, at the expense of the more newly discredited center-left. In addition, with both the mainstream center-left and center-right now associated with economic pain, there’s increasing support for new parties, some of them merely protest vehicles and others sometimes more radical, on both the left and the right. In Iceland, that means that two new parties, Björt framtíð (Bright Future) and the Píratar (Pirate Party of Iceland) will now hold one-seventh of the seats in Iceland’s Alþingi.

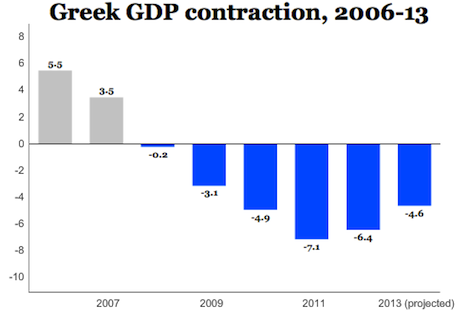

This is essentially what happened last year in Greece, too.  In the first step, Kostas Karamanlis and the center-right New Democracy (Νέα Δημοκρατία) initially took the blame for the initial financial crisis. In the second step, George Papandreou and the center-left PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement – Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα) overwhelming won the October 2009 elections, only to find itself forced to accept a bailout deal with the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In the third step, after two grueling rounds of election, Antonis Samaras and New Democracy returned to power in June 2012.

In the first step, Kostas Karamanlis and the center-right New Democracy (Νέα Δημοκρατία) initially took the blame for the initial financial crisis. In the second step, George Papandreou and the center-left PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement – Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα) overwhelming won the October 2009 elections, only to find itself forced to accept a bailout deal with the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In the third step, after two grueling rounds of election, Antonis Samaras and New Democracy returned to power in June 2012.

By that time, however, PASOK was so compromised that it was essentially forced into a minor subsidiary role supporting Samaras’s center-right, pro-bailout government. A more radical leftist force, SYRIZA (the Coalition of the Radical Left — Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς), led by the young, charismatic Alexis Tsipras, now vies for the lead routinely in polls, and on the far right, the noxious neo-nazi Golden Dawn (Χρυσή Αυγή) now attracts a small, but significant enough portion of the Greek electorate to put it in third place.

The process seems well under way in other countries, too. In France, for exam ple, center-right president Nicolas Sarkozy lost reelection in May 2012 amid great hopes for the incoming Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) administration of François Hollande, but his popularity is sinking to ever lower levels as France trudges through its own austerity, and polls show Sarkozy would now lead Hollande if another presidential election were held today.

ple, center-right president Nicolas Sarkozy lost reelection in May 2012 amid great hopes for the incoming Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) administration of François Hollande, but his popularity is sinking to ever lower levels as France trudges through its own austerity, and polls show Sarkozy would now lead Hollande if another presidential election were held today.

It’s not just right-left-right, though. The European three-step comes in a different flavor, too: left-right-left, and you can spot the trend in country after country across Europe — richer and poorer, western and eastern, northern and southern. Continue reading What Iceland’s election tells us about post-crisis European politics →

![]()

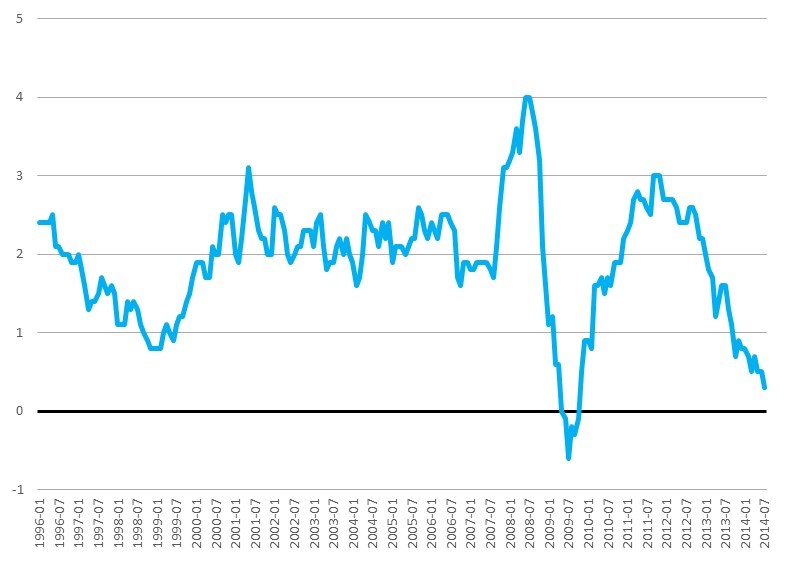

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much