Does the rise of an East German (or ‘Ossi’) chancellor in Germany just 15 years after reunification — and her likely reelection 23 years after reunification — showcase just how fast the two Germanies have sutured into a common nation?![]()

Or does it highlight the extent to which the eastern former German Democratic Republic (GDR) has failed to catch up with the western former Federal Republic of Germany (FRG)?

The six eastern German states are home to just 16.3 million Germans today, a vast minority of the country’s 80 million-strong population. But two days before Germans choose whether to give a third term to chancellor Angela Merkel (pictured above in 1990 as an activist for democracy in East Germany) — who was born in Hamburg, but grew up in the eastern city of Templin, in Brandenburg, where her father was a pastor — it all depends on whether you think the glass is half full or the glass is half empty.

Merkel comes from the Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Party), and it was her mentor Helmut Kohl who pushed for the swift reunification of Germany after the historic 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, which had since 1961 divided the eastern city of Berlin into GDR and FRG sectors.

By some accounts, the six states that comprise what used to be the GDR are doing as well as can be expected less than a quarter-century after transitioning from a command economy to a market economy, and the end of ‘East German identity’ is already at hand:

The end of a country is on the horizon, a country that never formally existed: East Germany. A demographic group that also never formally existed is coming to an end, as well: the East Germans. It’s time for an obituary…. The old eastern German issues have been dealt with. The adjustment of pensions to western German levels is almost complete, and hopefully a uniform minimum wage will clear away some of the absurd differentiation into east and west. Eastern Germany no longer means very much to high-school and university students today. When younger people are asked where they are from, they usually mention the name of a city, a region or a state.

After all, Germany has had an eastern chancellor for the past eight years and, since March 2012, an eastern president in Joachim Gauck who fought hard against the DGR’s authoritarianism before 1990 and spent the first decade after reunification chasing down the phantoms of the DGR’s secret police, the Stasi. The most significant transitional figure of post-reunification eastern politics, Matthias Platzeck, who has been minister-president of Brandenburg, the largest eastern state, since 2002 and a member of its government continuously since 1990, resigned for health reasons in August of this year.

Merkel and the CDU, according to polling data, are polling up to 37% — an increase from the 30% that the CDU won in the previous September 2009 elections.

But economic conditions in the six eastern states still lag behind the rest of Germany.

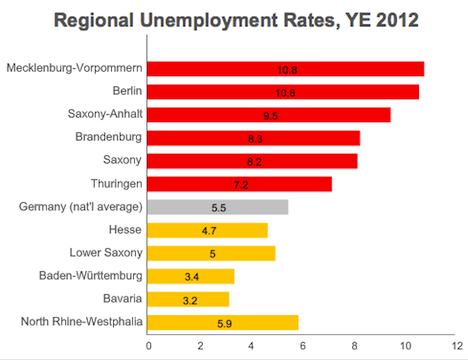

At the end of 2012, Germany’s unemployment rate stood at 5.5% (it’s 5.3% today going into the federal elections). In each of those six states, the unemployment rate was significantly higher than the national average — compare that to the five largest states, all of which are in what used to be West Germany:

Set aside the fact that part of Berlin was actually in West Germany (today, the city of Berlin is such a creative wonderland for Germans and Europeans alike, employed or otherwise, that it’s hardly fair to lump it in with the other eastern states). It’s clear that there’s an economic split between the eastern and western parts of Germany today.

The ‘stabilization fund’ designated to help transition the eastern states into a fully integrated Germany will be exhausted by 2019, which comes even after the likely next German election in 2017. Unless she follows in Kohl’s footsteps and pushes for a fourth consecutive term as chancellor, Merkel won’t be running the German government at that point. Maybe the fragile gains of the eastern states will collapse without those subsidies in place, but maybe the subsidies are distorting markets and the eastern states will start to really shine after the stabilization fund ends.

Cities like Dresden are now standout economic performers and CDU strongholds within Germany’s east, but Dresden — and Leipzig and even Magdeburg — are islands of economic growth in a region that spent decades as a communist, planned economy. It’s important to note that all of those cities are south of Berlin, so it doesn’t tell us that the eastern states (or some eastern cities) have incorporated the magic of western Germany’s success as much as they’ve incorporated the north-south divide that sees higher unemployment and lower incomes in northern Germany than in southern Germany.

Since reunification, turnout in the eastern states has also been lower than in the western states — 64.3 four years ago versus a national average of 70.8%:

“I wouldn’t be surprised if turnout in former East Germany dropped even lower this year,” says political scientist Gero Neugebauer of Berlin’s Free University. “People in the eastern states are increasingly disaffected with national politics — many feel disadvantaged and powerless to effect change.”

According to experts, the reason for the disparity is the political socialization that citizens — at least those old enough to remember — experienced under the communist regime. “It’s kind of a backlash,” says Neugebauer. “East Germans are intent on exercising their democratic right not to vote, after being forced to do so for many years.”

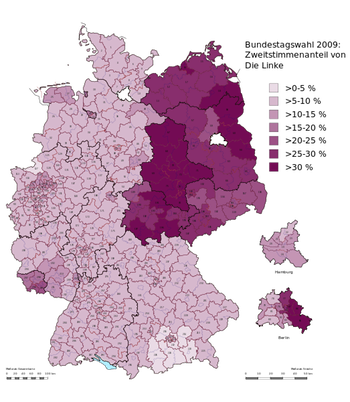

Furthermore, the democratic socialist Die Linke (the Left) is likely to vie with the CDU — and not the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) — as the main leftist challenger in the six eastern states (the Left won more votes in the previous election in Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt than any other party). Though the Left is likely to fall short of its nationwide 11.9% vote (and 76 Bundestag seats) that it won four years ago, polls show that it is still likely to win between 8% and 10% of the vote, largely on the basis of its strength in the east.

The Left started as the Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus (PDS, Party of Democratic Socialism) — a successor to the GDR’s communist Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SUD, Socialist Unity Party) between reunification and 2007, when it formally united (after an informal coalition in the 2005 elections) with a breakaway segment of leftist SPD members led by former finance minister Oskar Lafontaine. Its support has always been strongest in the former GDR, though, and its ties to the old Socialist Unity Party have made alliances between the SPD and the Left a politically radioactive possibility. Just check out a map of its electoral success in the previous election — it forms a near-perfect outline of the former GDR:

Katja Kipping (pictured below), one of the two co-leaders of the Left, was born in Dresden in 1978, and is one of those easterners shaped more by post-reunification Germany than the old GDR days. But though the Left has been plagued over the past four years by internal struggles between moderates and leftists, as well as by its western and eastern wings, it’s hard not to think of Kipping — instead of SPD chancellor candidate Peer Steinbrück — as the chief opponent to Merkel in the eastern states. A confident young leftist, she once called for a 100% tax on incomes over €40,000 a month as well as a guaranteed monthly income of €1,050, and she’s led a spirited campaign to get to the left of the rest of Germany’s mainstream parties — the Left wants to establish a German minimum wage of €10, even higher than the minimum wage that the SPD has proposed (€8.50).