Greece’s voters have effected a political earthquake in making leftist Alexis Tspiras their new prime minister, delivering a near-majority to the far-left and giving the European Union its first full-throated anti-austerity government since the onset of the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis in 2009-10.![]()

Tsipras’s party, SYRIZA (the Coalition of the Radical Left — Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς), is now the most left-wing governing party in the European Union and, with the exception of economist Yiannis Dragasakis, who served as deputy finance minister in a short-lived technocratic government a quarter-century ago, it’s a party with no significant governing experience.

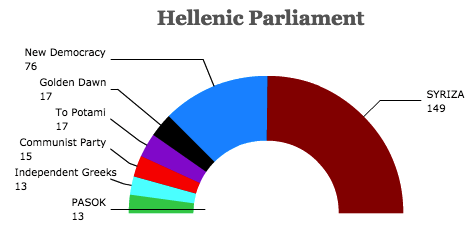

Despite a 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’ for SYRIZA, which significantly outpolled New Democracy, the party fell just short of an outright majority in Greece’s unicameral Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων). Earlier, today, however, Tsipras announced that he would form an alliance with the Independent Greeks (ANEL, Ανεξάρτητοι Έλληνες), an anti-austerity spinoff from New Democracy. Its leader, Panos Kammenos, last week scoffed that Europe is governed by ‘neo-Nazi Germans,’ and he is something of a loose cannon on the Greek political scene, and he has sometimes veered toward nationalist and even anti-Semitic rhetoric. Like Tsipras, he has brutally denounced the conditions of Greece’s two bailouts over the past half-decade, but he agrees on little else with the country’s new leftist prime minister.

Despite a 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’ for SYRIZA, which significantly outpolled New Democracy, the party fell just short of an outright majority in Greece’s unicameral Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων). Earlier, today, however, Tsipras announced that he would form an alliance with the Independent Greeks (ANEL, Ανεξάρτητοι Έλληνες), an anti-austerity spinoff from New Democracy. Its leader, Panos Kammenos, last week scoffed that Europe is governed by ‘neo-Nazi Germans,’ and he is something of a loose cannon on the Greek political scene, and he has sometimes veered toward nationalist and even anti-Semitic rhetoric. Like Tsipras, he has brutally denounced the conditions of Greece’s two bailouts over the past half-decade, but he agrees on little else with the country’s new leftist prime minister.

* * * * *

RELATED: EU should give Tsipras a chance to govern

RELATED: Meet Greece’s new economic policymakers

* * * * *

So what should you make of the fast-moving events in Greece and the aftermath of Sunday’s elections? Here are seven key lessons.

1. It’s not surprising that a pro-bailout government lost.

Even if the Tsipras government represents something very new in European politics, Samaras’s defeat is more the rule than the exception. There’s a sense that he and the center-right New Democracy (Νέα Δημοκρατία) won the 2012 elections only because voters blamed the center-left government of George Papandreaou and the center-left PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement – Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα) for accepting the first bailout and the conditions that came along with it.

But more generally, when economies tank so spectacularly as Greece’s did, it’s not surprising that Samaras’s reelection chances were so slim. Notably, though Greek GDP is growing for the first time in six years, unemployment today (25.8%), though it is gradually dropping, remains even higher today than it was at the time of the 2012 election. Samaras’s loss in 2015 is not unlike the center-left’s loss in Spain in 2011 or the center-right’s loss in Italy in 2013.

2. There’s a space for compromise between Berlin and Athens.

Though SYRIZA’s platform contemplates that the new government will be able to secure a debt haircut of up to half of Greece’s €320 billion public debt, it beggars belief to think that northern European leaders will be willing to forgive Greek debt, at the risk of angering far-right eurosceptics, on the rise in the United Kingdom, Sweden, Finland, France and now, even Germany, as well as their own taxpaying constituents.

There’s no doubt that Athens is headed into a high-stakes game of chicken with and Brussels and Berlin.

But that doesn’t mean there’s not room for a deal that would essentially relax some of the components of the Greek bailout program, extend short-term financing to the Greek government through 2016 that allows for, perhaps, some minor tax cuts and additional stimulative spending on education, health and social welfare spending or eve public-sector employment to jump-start Greece’s nascent economic recovery. In the long run, to the extent that Brussels, Berlin, Frankfurt and Athens all privately agree that the Greek debt load is unsustainable, a far more politically palatable option is to extend the repayment period at low (or close to zero) interest. Tsipras can also woo EU leaders with plans to collect more tax revenue owed to the government, especially from the wealthiest Greeks.

In a best-case scenario, that deal would give Tsipras the political space to declare an ‘end to austerity,’ with the natural forces of recovery and the quantitative easing of Mario Draghi’s European Central Bank, as announced just last week, doing much of the real work in making Greek voters feel more optimistic about the future.

3. SYRIZA isn’t a monolithic party.

Since 1991, when the first reform movement broke away from Greece’s neo-Soviet Communist Party, the concept of SYRIZA has grown organically in fits and starts. As recently as the 2012 elections, it was still just a loose coalition of small parties. Its unity is much stronger now that it’s the governing party, but that doesn’t mean that Tsipras is leading a 149-member caucus that always sings from the same hymnbook.

In particular, Tsipras will have to pacify Panagiotis Lafazanis (pictured above), the leader of a key faction within SYRIZA, Left Platform (Αριστερή Πλάτφορμα). To the extent that Tsipras moves too far to the center, Lafazanis will be there to remind Tsipras that SYRIZA remains an essentially socialist political movement. Though Tsipras moved the party significantly further to the center between 2012 and 2015, not everyone has been so enthusiastic about SYRIZA’s new pro-euro stand. Lafazanis would not be particularly upset to see Greece leave the eurozone and return to a much cheaper drachma.

4. Golden Dawn is down, but not out.

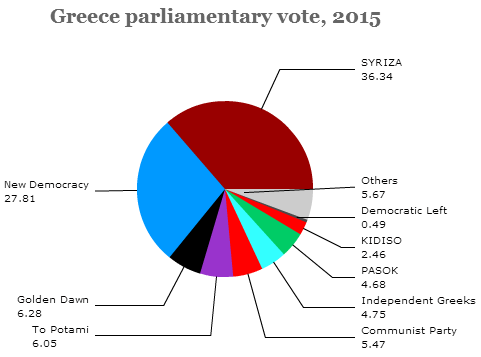

The far-right, fascist paramilitary Golden Dawn (Χρυσή Αυγή) will very narrowly remain the party with the third-largest amount of support in Greece. But the 6.28% that it won is below the 6.9% it won in the June 2012 election and far below the 9.4% it won just a few months ago in the May 2014 European parliamentary elections.

The outgoing Samaras government, by cracking down in 2013 on the party’s leadership in the wake of a fatal attack on a leftist protester, removed one of the potentially greatest headaches of a Tsipras government by neutralizing the threat of Golden Dawn’s leaders, many of whom are in prison for inciting hatred and violence. That Greek voters began to turn away from the anti-democratic, often blatantly neo-Nazi politics of Golden Dawn is a high point from the 2015 results.

5. Antonis Samaras’s political career is (probably) over.

Though polls consistently showed that SYRIZA narrowly led New Democracy during the campaign, SYRIZA’s final lead of around 8.5% is much better than most analysts expected.

As it turns out, Samaras (pictured at top) shares much of the blame for that result. Not only did he lead Greece’s government for the last 2.5 years, but it was his decision to force early elections by bringing forward the legislative vote on a new president, and it was his decision to campaign against SYRIZA in such harsh, nearly apocalyptic terms — both of which ultimately backfired against him.

Though New Democracy remains, as the chief center-right opposition, in much better shape than the withered PASOK, Samaras’s days as ND leader are almost certainly numbered. Kostas Karamanlis, prime minister between 2004 and 2009, criticized both Samaras’s political approach and his steadfast embrace of austerity policies. While Tsipras is said to be considering Karamanlis as a consensus choice to become Greece’s next president, Karamanlis’s son may make a play for the leadership. Kyriakos Mitsotakis (pictured above), another legacy of Greece’s political dynasties as the son of a former prime minister, and most recently a popular minster for administrative reform, is the more likely candidate to assume the ND leadership.

6. The traditional center-left is virtually extinct.

Since the return of democracy in 1974, PASOK was traditionally the dominant center-left force in Greek politics. But the rise of SYRIZA in 2012, with Greek voters disillusioned with the prior Papandreou government’s initial decision to accept the bailout terms.

But to the extent left-leaning voters didn’t already convert to the SYRIZA cause, they found themselves choosing among four separate parties in the 2015 election, including the Democratic Left (DIMAR, Δημοκρατική Αριστερά), one of two center-left parties, along with PASOK, that originally joined Samaras in Greece’s pro-bailout coalition in 2012. Though it ultimately withdrew from the government in 2014, that was too late to save it from losing all of its seats in Sunday’s election.

Papandreou (pictured above), for his part, formed a new party, KIDISO (Movement of Democratic Socialists, Κίνημα Δημοκρατών Σοσιαλιστών), splitting what was left of PASOK’s voter base, reducing PASOK to seventh place with less than 5% of the vote, something of a disaster for a decades-long franchise. Meanwhile, Greek voters, with fresh memories of Papandreou’s government, failed to give KIDISO enough support to win seats at all. It will be the first time since 1923 that a Papandreou hasn’t been a member of the Hellenic Parliament.

It also leaves the center-left in such disarray that PASOK’s extinction is a distinct possibility.

7. The SYRIZA-led coalition with the Independent Greeks will be awkward.

Among the potential coalition partners for Tsipras, moderates hoped that the new prime minister would have at least heard out the case to join forces with To Potami (Το Ποτάμι), a centrist party formed in 2014 by television journalist Stavros Theodorakis, which nearly became the third-largest party in the Hellenic parliament.

To the extent that the trend of Greek politics in the last two election cycles has been to polarize the electorate between pro-bailout and anti-bailout extremes, Theodorakis tried to find a middle way that prevents another Greek crisis or eurozone exit while also voicing a strong defense of Greek values and sovereignty. Even yesterday, Theodorakis indicated he would be willing to engage in coalition talks. As a party so new that it hasn’t been forced to support a bailout in either the Samaras or prior governments, it was as a particularly good fit for SYRIZA — and a potentially moderating one.

That Tsipras has so readily allied with Kammenos (pictured above), a right-wing firebrand with minor ministerial experience, did not soothe markets concerned about the new Greek government. It made for an odd twist, and it put Kammenos, whose party was in jeopardy of missing the 5% threshold to win any seats, in a position to become one of the most important politicians in Greece.

Gozo Island