In September, voters in some of Europe’s most economically stable countries (Germany, Austria and even Norway) happily turned out to support their incumbent governments. But in October, the Czech Republic’s election demonstrates that most of Europe remains under incredible social, economic and political stress.

Czech voters selected members to the lower house of the Czech parliament between two days of voting on Friday and today. The result is a fragmented mess — it’s the most fractured election result since the May 2012 Greek parliamentary election, which resulted in a hung parliament and necessitated a second set of elections in Greece just a month later.

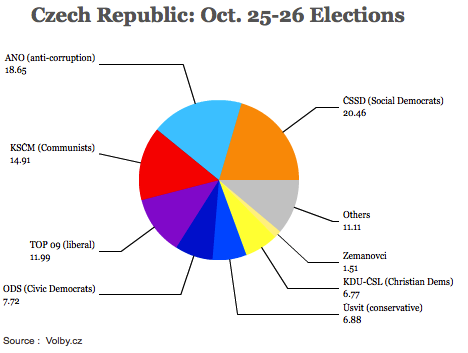

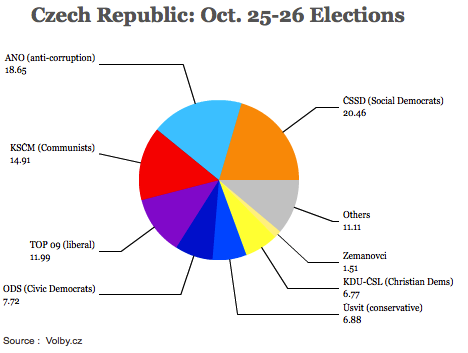

Here are the results:

Seven different parties — ranging from free-market liberals to communists to political neophytes — won enough votes to gain seats in the 200-member Poslanecká sněmovna (the Chamber of Deputies), but it’s not clear who will be able to form a government. Voters clearly rejected the previous center-right government’s approach to austerity and budget discipline, but split over what they want to replace it. Turnout fell below 60% for the first time in over a decade.

In purely political terms, the result gives even more power to Czech president Miloš Zeman (pictured above), who came to office after winning the country’s first direct presidential election in January. On the list of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in this weekend’s election, perhaps no one is a greater winner than Zeman, who is entitled to appoint the prime minister and therefore, will shape the first steps in the coalition negotiations.

Since taking office, Zeman has pushed to empower the Czech presidency at the expense of the Czech parliament. After the country’s center-right government fell earlier this summer, Zeman appointed Jiří Rusnok as his hand-picked technocratic prime minister, but Rusnok’s (and Zeman’s) inability to win a vote of confidence led to this weekend’s snap elections. Rusnok has served as a caretaker prime minister for the past three months, and he could wind up serving quite a while longer if no governing coalition can be formed.

The center-left Česká strana sociálně demokratická (ČSSD, Czech Social Democratic Party) technically won the election — but just barely, and with far less support than polls showed just a month ago. Despite winning more votes than any other party, the Social Democrats won just one out of every five votes, and it’s the party’s worst result in two decades. It’s not necessarily clear that the party’s leader, former finance minister Bohuslav Sobotka, will even have the chance to form a government. There’s simply no credible case that the Social Democrats have a mandate for much of anything.

Though Zeman, a Social Democratic prime minister between 1998 and 2002, broke away from the Social Democrats only in 2007, the party remains divided over the extent to which it wants to associate with Zeman now that he holds the Czech presidency. What’s certain is that the poor result will weaken Sobotka, who leads the anti-Zeman wing of the party. That means Zeman could bypass Sobotka and appoint a friendlier Social Democrat as prime minister, such as deputy leader Michal Hašek or perhaps Jan Mládek, who was widely tipped to become the next finance minister.

The real winner in today’s election is the Akce nespokojených občanů (ANO, Action of Dissatisfied Citizens), founded in 2011 by millionaire Andrej Babiš, which nearly overtook the Social Democrats in terms of support — they will hold just three fewer seats than the Social Democrats in the new Chamber of Deputies. Babiš is one of the wealthiest businessmen in the Czech Republic, and he’s led a ‘pox-on-all-your-houses’ campaign that rejects the mainstream Czech political elite as corrupt and dishonest. Babiš owns founded Agrofert, originally a food processing and agricultural company, but now a conglomerate that’s the fourth-largest business in the Czech Republic. Though his platform is relatively nebulous, he’s called for reforms to reduce corruption and end immunity for politicians from prosecution.

Think of Babiš as a cross between former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi and Georgian prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili, perhaps, and think of ANO as a more business-friendly version of Beppe Grillo’s Italian protest group, the Five Star Movement. Given Babiš’s recent effort to buy a top Czech media company, the comparisons to Berlusconi have become particularly sharp:

A Czech tabloid recently nicknamed Andrej Babis, the new star on the Czech political scene, “Babisconi.” But, when compared with Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi, he quips: “I have no interest whatsoever in underaged girls.”

In third place is the Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy (KSČM, Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia), which won about 15% of the vote, the party’s second-best result since the fall of the Soviet Union. The party is the heir to the old Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, which governed the country from 1968 until 1990 as a Soviet-aligned, one-party state. Though the Communists have moderated their approach somewhat in the 21st century, and though they were expected to participate in a Social Democratic-led government, the party remains unapologetically communist (unlike other former eastern far-left parties, such as Die Linke in Germany, which espouse a more moderate form of democratic socialism). Given that the base of the Czech Communists was once older, rural voters, its comeback today says much about the economic despair in the Czech Republic these days. Continue reading Czech election results: a fractured and uncertain Chamber of Deputies →

![]()

![]()