It’s a sign that fiscal affairs in Greece are bad when the sensible Plan B to cover the Greek government’s looming shortfall involves loans from Moscow (despite protests to the contrary).![]()

Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras has dismissed European sanctions against Russia, and he met Russian president Vladimir Putin in Moscow earlier this week, signaling to the European Union that Greece is keeping its options open if ongoing debt talks fail. Though Tsipras didn’t seek any financial assistance from Putin, he failed to convince Putin to lift a ban on Greek agricultural exports.

The even more outlandish Plan B involves demanding reparations from Germany for World War II damages, amounting to €278.7 billion. Perhaps not coincidentally, that’s just a little more than the €240 billion in financing that Greece has received in the last half-decade under two bailout programs from the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Today, Greece’s government, not even three months old, will repay a €460 million portion of its debt to the International Monetary Fund. But that doesn’t mean that all is well in Athens, where last year’s green shoots of economic recovery are now obscured by the uncertainty of a leftist administration that’s engaged in brinksmanship over Greece’s financing and, ultimately, over the wider question of national fiscal sovereignty in today’s eurozone.

* * * * *

RELATED: EU should give Tsipras a chance to govern

RELATED: What a Eurogroup-brokered deal with Greece might look like

RELATED: Seven lessons from the Greek election results

* * * * *

Why Tsipras can’t (and won’t) make a deal on Berlin’s terms

Without a deal, Tsipras will go down in history as the prime minister who led Greece out of the eurozone, willingly or not. Politically, however, Tspiras can’t agree to any deal that the Eurogroup seems to be offering. That’s increasingly a recipe for Tsipras to call fresh elections early this summer, but there’s no guarantee the results will solve the Greek-EU political quagmire.

Tsipras and his anti-austerity SYRIZA (the Coalition of the Radical Left — Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς) were elected three months ago on a pledge to renegotiate the terms of Greece’s debt with its European lenders and end the harsh austerity measures that have exacerbated Greece’s contracting economy and growing unemployment. But the EU’s leaders, including Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker, German chancellor Angela Merkel and, presumably, ECB president Mario Draghi, no longer fear the ‘contagion’ effect of a Greek eurozone exit.

Tsipras’s ability to make a bargain with Greece’s lenders is constrained by at least three domestic considerations:

- First, even the IMF’s Christine Lagarde and others have agreed with Tsipras that the conditions of Greece’s first two bailouts contributed adversely to the country’s economic misery. So Tsipras has made a strong point that his government should have enough time and space to develop an organic economic policy that attempts to correct Greece’s economic trajectory. So far, however, the government doesn’t seem to have the credibility to make good on its promise to do so. Though the temporary deal in February provided Tsipras with much more leeway to set policy (including optimistic plans to crack down on tax evasion and Greece’s ‘gray market’), it hasn’t inspired much confidence.

- Second, Tsipras won an overwhelming mandate to do exactly what he’s doing — defiantly standing up to Greece’s creditors in hopes of obtaining better terms for future financing. If Tsipras’s position seems unreasonable, even to sympathetic ‘pro-growth’ Europeans of the center-left, it’s because the Greek electorate gave elected him to take that position. If that causes short-term economic pain, well, no one said it would be an easy path to pick a proxy fight with northern Europe over the eurozone’s fiscal policy and the balance of power between EU governance and national sovereignty. It’s a high-stakes political showdown that mirrors the long-running theoretical clash between ‘intergovernmentalists’ and ‘neofunctionalists.’

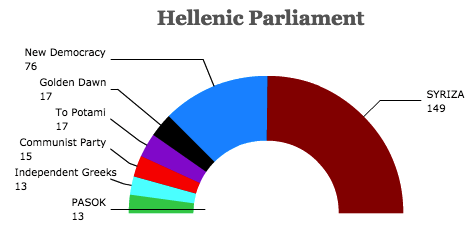

- Third, SYRIZA’s far-left wing faction, Left Platform (Αριστερή Πλάτφορμα), would oppose any Tsipras-led attempts to come to an agreement acceptable to the entire Eurogroup. Led by energy minister Panagiotis Lafazanis and commanding 30 to 40 MPs in Greece’s 300-member Hellenic parliament, Left Platform holds veto power over any Greek deal, at least so long as Tsipras refuses to work with Greece’s other centrist parties. It’s worth noting that until the last election, SYRIZA itself was just a loose coalition of leftist parties. If economic conditions continue to deteriorate, SYRIZA’s unity isn’t necessarily assured.

In the short term, if Tsipras can’t make a deal with the Eurogroup, and if Greece can’t muddle through without further financing, Tsipras will almost certainly call snap elections soon. To the extent that the current path will force Greece out of the eurozone, and to the extent that most Greeks want to keep the single currency, a new election campaign would be a shadow referendum on that issue, though Tsipras is very unlikely to frame it in those terms. Nevertheless, polls show that voters still favor SYRIZA — a Metrisi poll from early April gives SYRIZA 40.3% of the vote (around 4% more than it won in the January election) to just 27% for the center-right New Democracy (Νέα Δημοκρατία).

A governing shakeup in Athens?

The Financial Times is reporting that many Europeans (and a few Greeks) are speculating a way out for Tsipras that avoids default, which could wreck Greek and European finances alike, and snap elections, which would only fuel greater political instability. The idea is that Tsipras would dump both the Left Platform and his anti-austerity, nationalist conservative coalition partner, the Independent Greeks (ANEL, Ανεξάρτητοι Έλληνες), and instead form a government with what used to be Greece’s center-left party, PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement – Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα), and a new centrist party, To Potami (Το Ποτάμι):

“Tsipras has to decide whether he wants to be prime minister or the leader of Syriza,” said one European official. A senior official in a eurozone finance ministry added: “This government cannot survive.”

Members of Syriza’s moderate wing admit there is a problem with the Left Platform, the official internal opposition that represents about a third of the party and controls enough MPs to bring down the government if it were to rebel in a parliamentary vote. “We used to be more debating society than political party . . . so it is hard to get a system of party discipline up and running,” said one Syriza official. “But you have to remember — we’ve been in power less than 100 days.”

But those coalition mathematics are difficult. With the Independent Greeks, SYRIZA has a 12-seat majority within the 300-member Hellenic parliament. That gives Tsipras some room for creativity, but To Potami and PASOK hold just 30 seats in aggregate. If Tsipras replaced the Independent Greeks with the two centrist parties, he could afford to lose just 25 of SYRIZA’s most left-wing MPs. That could open the door to even greater instability.

Former prime minister Antonis Samaras, who still leads New Democracy, has in recent days offered his own party’s support for a unity government that would support Tsipras in an effort to reach a deal that keeps Greece in the eurozone. If it’s hard to imagine Tsipras splintering SYRIZA and partnering with PASOK, it’s incomprehensible that he’d join forces with the Greek right. Any of these coalition variants, moreover, risk painting Tsipras in the same light as Samaras and former prime minister George Papandreou. Greek voters elected Tsipras to take a different path.

Russia, reparations and rabble-rousing

Furthermore, a government that’s flirting with Russia and that has renewed calls for German reparations doesn’t seem like it’s in a mood for unity coalitions and dealmaking. The reparations point, in particular, is a controversial issue in Greece, where Germany’s Nazi government forced the central bank to issue it a loan in 1942 that equals around €11 billion. Though the German government paid some reparations in 1960, many Greeks believe it was insufficient, and even German green and leftist opposition politicians argue that reopening the reparations issue (insofar as it involves the 1942 forced loan) isn’t entirely out of the question.

Nevertheless, Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s vice-chancellor and economy minister, who belongs to the center-left Social Democratic Party and who might otherwise be more sympathetic to the leftist Tsipras, has called the Greek government’s call for reparations ‘stupid.’ Conservative finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble, whose relations with Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis are particularly cool, said the issue had been ruled out decades ago.

Merkel, for what its worth, ruled out further reparations, but took pains to do so gently and respectfully, acknowledging the Nazi-led atrocities committed by her country during World War II. Merkel received Tsipras two weeks ago in Berlin in a summit designed to ease tensions between the two countries.

Russia and reparations aren’t the only provocations. Last month, defense minister Panos Kammenos, the leader of the Independent Greeks, SYRIZA’s junior coalition partner, made a veiled threat that the European Union’s failure to support Greece could weaken border defense, allowing Islamist jihadists into the EU’s free movement zone.

Proxy fight over fiscal sovereignty

Tsipras’s struggle to win greater concessions from Brussels and Berlin is symbolic of a larger fight between unelected European federalists and the sovereignty of elected national governments. If the European institutions and the German government cave to Tsipras, it will encourage left-wing parties in other austerity-struck, economically depressed countries (notably Spain, where the anti-austerity Podemos leads polls in advance of a general election later this year). But it will also encourage nationalists everywhere to demand their own concessions, thereby weakening European unity. That will be especially true if British prime minister David Cameron is reelected and fulfills a pledge to renegotiate British EU membership in advance of a promised 2017 in-or-out referendum.