Five days before the Christmas holiday, Spanish voters will go to the polls to choose a new government in an election that’s being hailed as the country’s most important since 1982.![]()

Indeed, voter turnout may well exceed the 80% levels not seen since 1982, when Spain had only just emerged from its Francoist dictatorship and was four years away from joining the European Economic Community, the predecessor to today’s European Union. Moreover, it will also be the first general election to take place under Felipe VI, whose father Juan Carlos I abdicated in June 2014 after guiding the country’s transition to democracy in the mid-1970s.

But what makes the December 20 election so unique is that economic crisis has shattered Spain’s stable two-party electoral tradition, leaving a four-way free-for-all that could force unwieldy coalitions or a minority government at a time when the country has only just started its economic recovery. Distrust in both major parties, moreover, has opened the way for a popular far-left movement at the national level and greater discord at the regional level, most notably in Catalonia, where support for the independence movement is growing. No matter who wins power in the eurozone’s fourth-largest economy, the next Spanish government will face difficult decisions about GDP growth, lingering unemployment, and federalism and possible constitutional change.

For decades, Spanish elections were essentially, at the national level, a fight between the conservative Partido Popular (PP, the People’s Party) and the center-left Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party). In the most recent 2011 election, the PP won 186 seats in the 350-member Congreso de los Diputados (Congress of Deputies), the Spanish parliament’s lower house, while the PSOE won 110 seats.

Both parties can point to massive successes over the past three decades. Under longtime PSOE prime minister Felipe González, Spain consolidated its liberal democracy and benefited greatly from closer economic and financial ties to Europe, while Barcelona’s emergence as the host of the 1992 Summer Olympics catapulted it into a world-class city. Under conservative prime minister José María Aznar, Spain joined the core of western European countries as a founding member of the eurozone in 2002 and developed widening security ties with the United States. When the PSOE returned to power in 2004 under José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the government enacted same-sex marriage in 2005 and later negotiated a peaceful ceasefire with the paramilitary Basque nationalist group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA).

The pain in Spain

But the global financial crisis of 2008-09 and subsequent eurozone crisis of 2010 knocked Spain off its pedestal.

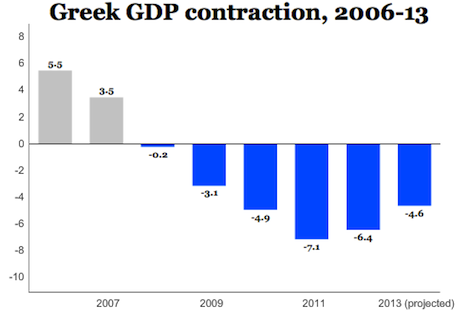

Not unlike Florida, Nevada and parts of California in the United States, property values in Spain fell as rapidly as they once climbed, and an economy driven by construction and easy credit sputtered to near-depression levels of contraction. Despite running a more parsimonious fiscal policy in the 2000s than even Germany, Zapatero’s government soon found its expenses far exceeding revenues, and his government engaged in a series of tax increases and spending cuts.

The Spanish electorate ousted Zapatero in December 2011, ushering the People’s Party back to power under Mariano Rajoy, whose main goal was to prevent Spain from needing to seek an emergency bailout. Despite some scares over the Spanish banking system in 2012, Rajoy succeeded in keeping Spain bailout-free, but at the cost of ever greater spending cuts and tax hikes. The Rajoy government’s tough fiscal medicine, to some degree, has worked. Yields on Spanish 10-year debt have steadily fallen from a high of over 7.2% in July 2012 to less than 1.8% today. For a country without economic expansion since 2008, the Spanish economy returned to fragile growth in 2014, and it maintained growth throughout 2015 — notching 1% growth in the second quarter of this year and 0.8% in the third.

But voters are not enthusiastic about the prospects of reelecting Rajoy, a leader who never quite managed to win over Spanish hearts. Spain’s unemployment rate today is still 21.2%, a drop from the record-high 26.9% level recorded in early 2013. But that’s still a far higher jobless rate than anywhere else in the European Union (with the exception of Greece).

In the 2008 election, before the bottom fell out of the Spanish economy, the two major parties together won 83.8% of the vote. By 2011, that percentage fell to 73.4%. If polls are correct, that percentage could fall below 50% on Sunday, as both the PP and the PSOE struggle against the surging popularity of the anti-austerity Podemos (‘We can’) on the left and the liberal, federalist Ciudadanos (C’s, Citizens) on the right.

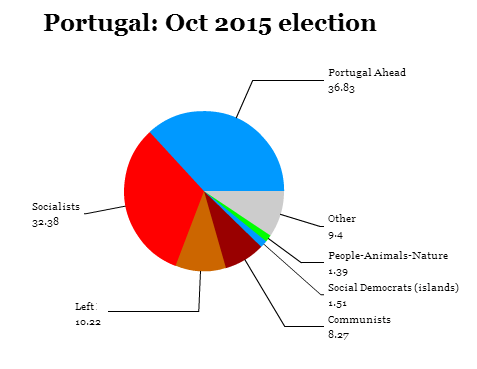

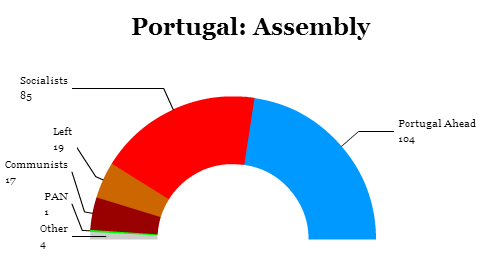

If the election were held today, the PP would win around 110 seats, the PSOE around 90, and Podemos and Ciudadanos would each win around 60, leaving none of them with a clear majority. The uncertainty of the four-way race has both energized the electorate (in a manner reminiscent to those first early elections in the post-dictatorship era) and enhanced the chances of post-election uncertainty that both Greece and Portugal have endured this year. Continue reading Spain readies for historic, four-way election on December 20

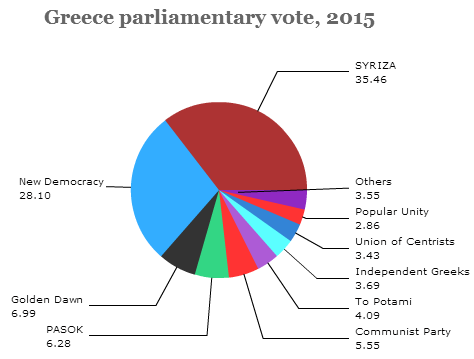

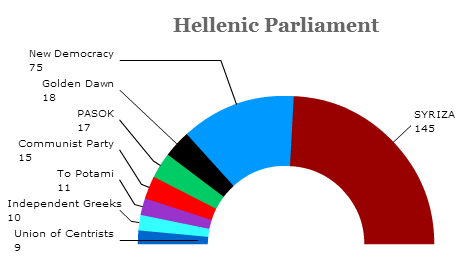

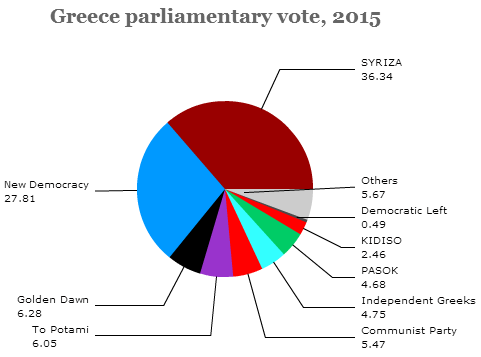

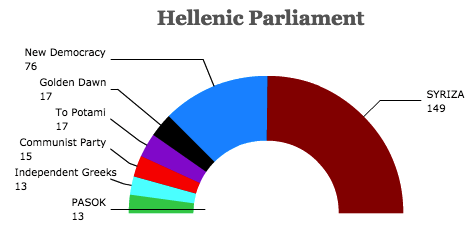

Despite a 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’ for SYRIZA, which significantly outpolled New Democracy, the party fell just short of an outright majority in Greece’s unicameral Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων). Earlier, today, however, Tsipras

Despite a 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’ for SYRIZA, which significantly outpolled New Democracy, the party fell just short of an outright majority in Greece’s unicameral Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων). Earlier, today, however, Tsipras