On Wednesday, the incoming president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker (pictured above), released full details on the proposed commissioners within his Commission, which will serve as the chief executive and administrative body of the European Union between 2014 and 2019.![]()

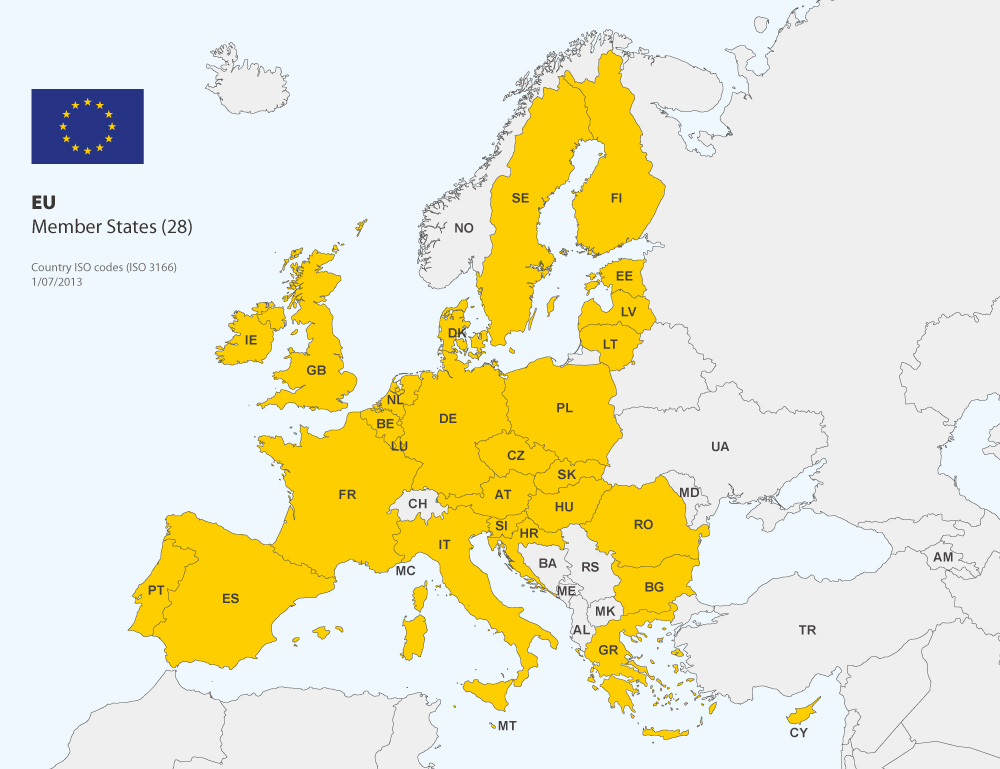

The most important feature of the proposed Juncker Commission is that he’s introduced the greatest amount of hierarchy in an institution that used to be flat. It’s not a secret that some portfolios have always been more desirable than others, especially as the Commission has expanded to include all 28 member-states. But Juncker has introduced a first vice president and five vice presidents, who will also serve alongside Italy’s foreign minister Federica Mogherini, who was appointed two weeks ago to serve as Commission vice president and high representative for foreign affairs and security policy.

The delegation of so much power to five ‘super-commissioners’ with roving, supervisory briefs indicates that Juncker intends to be a much less hands-on Commission president that his predecessor, José Manuel Barroso. But it also reflects a Commission that, including Luxembourg’s Juncker, contains five former prime ministers (Finland, Slovenia, Latvia and Estonia). It also contains four incumbents (Germany, Sweden, Bulgaria and Austria) who have served throughout the full second term of the Barroso Commission. That makes the Juncker Commission possibly the most distinguished in EU history.

Each commissioner must be approved by the European parliament and, while individual nominees have had troubles in the past, the parliament typically approves the vast majority of a Commission president’s appointments, all of whom were nominated by their respective national governments.

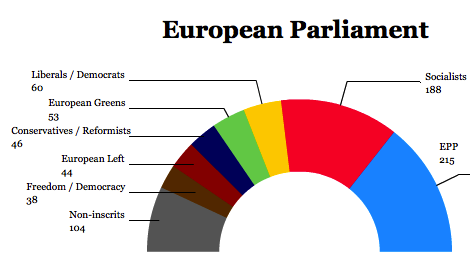

With nine women, it’s not as unbalanced as feared even a week or two ago, and with 14 members of the center-right European People’s Party (EPP), eight members of the center-left Party of European Socialists (PES) and five members of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), it generally reflects the results of the May 25 European parliamentary elections, though some social democrats and socialists are grumbling that the left doesn’t have enough representation.

So what can we expect from this illustrious college of commissioners?

Here’s a look at the 13 most important players in the proposed Commission (aside from Juncker and Mogherini, of course). Continue reading The 13 key EU players in the proposed Juncker Commission