Consider Italy’s new government renzismo without Renzi.![]()

A week after Matteo Renzi failed, in spectacular measure, in his efforts to win Italian voter approval of his ill-fated referendum on political reform, Italy has a new prime minister after consultations between Renzi, other political leaders and Italian president Sergio Mattarella.

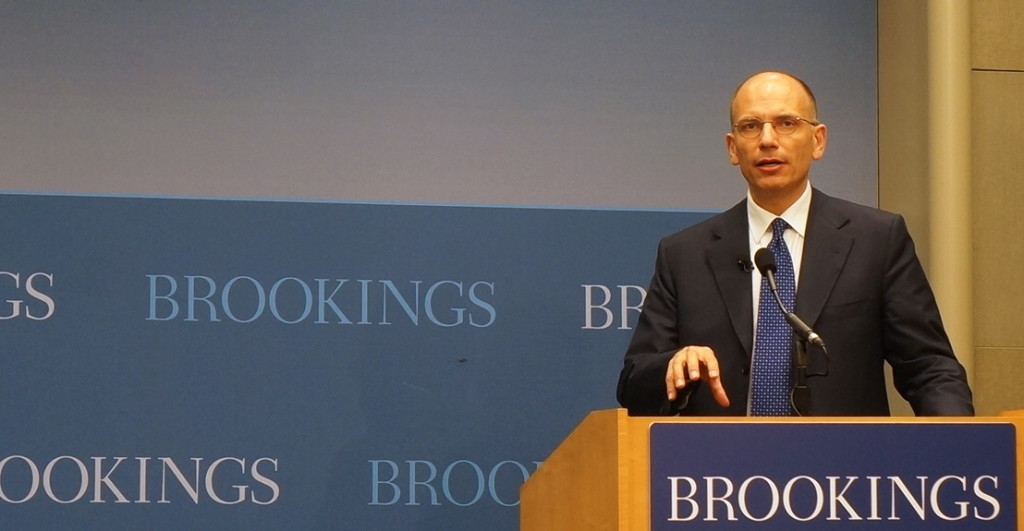

With no more than 15 months (and likely far less) until the next general election, Italy’s new premier Paolo Gentiloni will lead a government that looks much like the one Renzi led until last week — one dominated by the centrist and reformist wing of Italy’s center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party).

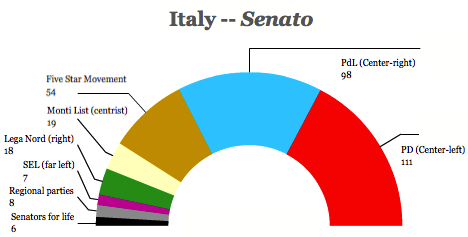

Given that the Democrats and their centrist allies retain a majority in the lower house of the Italian parliament, the Camera dei deputati (Chamber of Deputies), it was almost certain that Mattarella would appoint someone from the Italian left. It was not certain that Mattarella would turn to a Renzi ally, however, given the longstanding tradition of non-partisan ‘technocratic’ governments in Italian politics. Still, Gentiloni was a colorless Roman aristocrat with an undistinguished political career until his sudden ascent to foreign minister two years ago. He replaced Federica Mogherini, who departed Renzi’s government in 2014 to serve as the EU high representative for foreign affairs and security policy. Today, Mogherini remains a rising star who may yet eclipse even Renzi from her perch as Europe’s top diplomat.

Gentiloni, who hails from Roman nobility, began his career in journalism, switching to politics in the 1990s as an ally of Francesco Rutelli, a former centrist mayor of Rome from 1993 to 2001. Both of them served in the short-lived government of Romano Prodi from 2006 to 2008; Rutelli as deputy prime minister and culture minister, Gentiloni as communications minister. In the center-left primary to determine the party’s candidate in the 2013 Roman mayoral election, Gentiloni finished in third place with just 14% of the vote.

Despite strong marks for his time as foreign minister, no one expects Gentiloni to remain prime minister longer than the next election, no matter who wins.

* * * * *

RELATED: Renzi’s referendum loss isn’t the end of the world

for Italy or the EU

* * * * *

Gentiloni, instead, looks more like a caretaker who will lead the government through rough months ahead while Renzi licks his wounds back home in Florence and prepares for the next election.

Perhaps most consequentially for Europe (and global markets), Gentiloni’s cabinet retains Renzi’s finance minister Pier Carlo Padoan, himself seen as a potential successor to Renzi. Other key ministers retained include defence minister Roberta Pinotti and justice minister Andrea Orlando, while Angelino Alfano, previously interior minister, will assume Gentiloni’s new role as foreign minister.

Italian banks on the brink

Gentiloni and Padoan will turn most immediately to efforts to calm markets about Italy’s tottering banks and, in particular, the Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS). Increasingly, it seems likely that the bank, the world’s oldest (dating back to 1492, will require a bailout from the government, potentially angering taxpayers. Potentially, the government might also require a ‘bail-in’ of the bank’s investors, potentially angering Italy’s capital class. Other Italian banks in need of capitalization may come in for the same treatment. Essentially, Italian banks today find themselves in much the same position as American banks in 2009 — undercapitalized and sitting on far too many non-performing loans. While the U.S. bailout in 2008 and 2009 was far from popular, in today’s climate, in a country like Italy, where joblessness and listless (or negative) growth have become endemic, a bailout could be far more toxic.

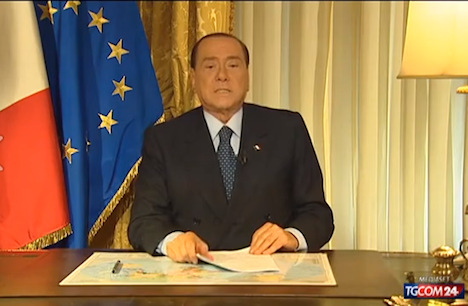

Renzi may believe that, by leaving such unpopular steps to Gentiloni and Padoan, he can emerge later in 2017 or 2018 for a comeback — not unlike Silvio Berlusconi, himself forced from office twice, despite dominating Italian politics for nearly two decades.

That may be too clever by half. Continue reading What to expect from Italy’s new government