If there’s anyone in European politics who straddles the line between the two cultural realities of Europe today, it’s Jorgo Chatzimarkakis.![]()

![]()

![]()

Born in 1966 to Greek migrants in the Ruhr Valley, in what was then West Germany, Chatzimarkakis has served for the past 10 years as a member of the European Parliament from Germany’s liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party).

Over the course of the past five years, that’s put Chatzimarkakis in one of the most unique roles of any European policymaker. As a German MEP, he belonged to a party that was one of the most outspoken critics of using German funds for what seemed, at the heart of the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis, like an endless number of bailouts for troubled European economies, including Greece’s.

But as an MEP of Greek descent, Chatzimarkakis also understood the emotional and social toll of the economic crisis from the other perspective, in light of the pain Greece continues to suffer due to the bailout — often referred to in Greece simply as the ‘memorandum,’ in reference to the Memorandum of Understanding that sets out the terms of the Greek bailout with the ‘troika’ of the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund.

* * * * *

RELATED: In-Depth: European parliamentary elections

* * * * *

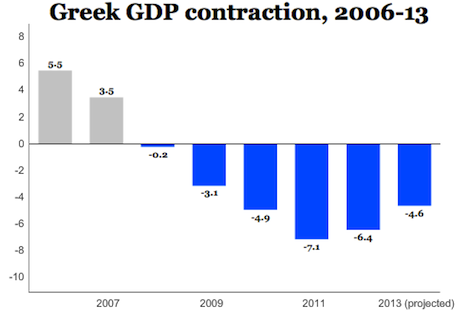

Though the bailout program has kept Greece inside the eurozone, it’s come at a huge cost. The conditions Greece accepted in exchange for the loan program required tough budget cuts, tax increases, and reduced state salaries and pensions, exacerbating an economic downturn that, for Greece, has now developed into a full-blown depression. Unemployment is still nearly 27%, youth unemployment is even higher, and the Greek economy has contracted for six consecutive years:

Cuts to education, health care and other programs have strained the Greek social fabric, civil strife and strikes are seemingly endless, and politician violence has increased. The neo-fascist Golden Dawn (Χρυσή Αυγή) is now the third-largest party in the Hellenic Parliament, despite the efforts of the current national government to prosecute many of its leaders. Though Greece’s economy may expand this year, for the first time since 2007, it’s clear that the effects of the downturn will reverberate for years to come.

In the 2014 European elections, Chatzimarkakis is running for the European Parliament in Greece, having formed a new political party, the Hellenic European Citizens (Έλληνες Ευρωπαίοι Πολίτες).

Polls show that the European elections in Greece will be a tight contest between the leading party in its current government, the center-right New Democracy (Νέα Δημοκρατία) of prime minister Antonis Samaras, the anti-austerity, leftist SYRIZA (the Coalition of the Radical Left — Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς) that has gained extraordinary support during the economic crisis.

SYRIZA’s leader, Alexis Tsipras, is the candidate of the pan-European Party of the European Left for the presidency of the European Commission, giving Tsipras a high-profile role as one of the leading EU-wide voices of the socialist left. There’s a strong chance that the European elections could serve as a prelude to snap national elections in Greece later this year.

Though forming a pro-European party in Greece in 2014 might seem like a fool’s mission, there’s no guarantee that Chatzimarkakis would have won reelection in Germany, where Chatzimarkakis has increasingly clashed with the FDP leadership over the course of the eurozone crisis. FDP and other government officials scoffed at his proposal for a ‘Hercules plan,’ a 21st century analog to the Marshall Plan that would have provided investment funds to the eurozone’s crisis-stricken countries.

But even if Chatzimarkakis wanted to run on the FDP ticket, it would still be an uphill battle. The FDP, which served in chancellor Angela Merkel’s coalition government between 2009 and 2013, lost all of its national parliamentary seats in the German election last September, and it’s forecast to lose all 12 of its seats this weekend in the European Parliament. Chatzimarkakis also suffered a personal setback when the University of Bonn revoked his doctorate after parts of his dissertation were determined to have been plagiarized.

Undaunted, Chatzimarkakis launched his new party in January:

Launching his party, called Greek European Citizens, at the offices of the European Parliament in Athens, Chatzimarkakis criticized German policies opposite Greece and Europe and described the troika as “a supposedly technocratic body” that has compromised “basic democratic rights and citizens’ incomes.”

He accused Germany of having “double standards” and described the austerity policies it has championed in Greece and other EU member states as “a dead end.”

I had a chance to speak with Chatzimarkakis early Friday morning by telephone from Athens, where he was wrapping up his campaign for the Europe-wide voting, which started on Thursday in the United Kingdom and The Netherlands. Greece is voting on Sunday, the final day of the elections, and results are expected to be announced later that day.

KL: How is the campaign going?

JC: It’s the first time in my life that a campaign goes only positive. It’s the fourth time that I’ve run for the European Parliament — no, it’s the fifth time — of, course, the first four times in Germany. But I’ve never [run] before when all the reactions I’ve gotten are 100% positive. This is, of course, encouraging, as you can imagine, but it has to do with a different message that I’ve sent to people. I give people different things than they are used to, because I come from a different political environment. So I’m something new to the Greek environment and, obviously, it is being accepted positively.

KL: It’s a tough time for the FDP in Germany these days, but it seems like an even more uphill fight forming a new pro-Europe movement in Greece. Tell me why you decided to contest this election from Greece, and not Germany. And why form a new movement? Why not ally with To Potami [a new, centrist and pro-European party founded in February 2014], for example?

JC: OK, there’s two answers, two questions.

First, the last four years were very hard for me, being a German member of Parliament but of Greek descent, because in 2010, when the financial crisis broke out, the German government, including my party, began to ‘aggress’ Greece in a very unpleasant way. The political behavior was not acceptable, the way the government and parts of the media were really ‘aggressing’ the Greek people. The Germans understood that two years later and stopped talking about the ‘Grexit.’

For me, the decision to not run anymore in Germany was taken when the German minister of economics [the FDP’s Rainer Brüderle] called a proposal of mine to create an ESM [European Stability Mechanism] — and that was in 2010.

In 2010, we didn’t have an EFSF [European Financial Stability Facility], so we didn’t have any mechanisms to rescue an economy. When I presented this plan, I was called by this minister at a ministerial conference of the German government a ‘Cretan shepherd.’ He said, ‘we do not need to discuss here plans by Cretan shepherds.’ That caused within me a violent revolution. So I stayed in the party, but only in order to become an opponent of German policy within the party.

I decided later, now answering the second question, to run in Greece because I thought I could help the political system, because the Greek political system is not able to cope with the crisis. I wanted to help with my experience, with my knowledge and also with people that I knew, with my network, to get out of this crisis.

Soon I understood that the Greek political system didn’t accept that, because it’s a clientelistic, closed system. They didn’t want any help, they wanted to keep on moving in their corrupt, clientelistic system. So the only way to offer to the Greek people who don’t believe in clientelism, who don’t believe in corruption was to create a new party. So that is what we did.

I can see, especially in the last days of this pre-election campaign, that people welcome this. It’s very, very encouraging. The only thing they tell me is, ‘Why didn’t you start earlier?’ The answer is I couldn’t, because the Greek political system is a closed system, it’s a closed shop, it would have excluded be earlier from TV, so I’ve had to make the campaign very, very short knowing this, and now we have to wait for Sunday. We’ll see.

KL: You mentioned the eurozone crisis. How could the EU’s institutions have more smoothly handled the Greek debt crisis? If you could go back in time to 2009, if you were the ECB president or the Commission president or the German chancellor, what would you have done differently at the European level?

JC: One single thing. [ECB president] Mario Draghi said it two years too late. He should have said — well, he wasn’t president of the European Central Bank then, but the president of the central bank should have said it in 2010 when the crisis broke out. It’s a simple thing to say: we will do whatever, whatever, it takes to rescue Greece and rescue the eurozone. Full stop. That would have calmed down the market. Unfortunately, there was no plan at the beginning in the German government, and that’s why I became an anti-FDP politician within the FDP.

They did the opposite — they challenged the question, whether or not Greece should exit the eurozone, and that caused all the trouble. So the price for rescuing went up. When the Germans discovered they were a net winner in the situation, seeing their interest rates went down on their bonds while the interest rates of southern countries went up, this created an enormous internal machinery of money going back to the northern countries, to the richer countries… [the Germans] made a net benefit, whereas especially Greece, was the main loser.

One single example of what could have been done differently is Spain. Spain got hundreds of billions of euros of rescue without any memorandum, without troika, without this policy of degradation, and this shows that it was really a policy against Greece that was made by the German government. It’s not acceptable, and that is why I went to Greece and am trying to campaign here now.

KL: Greece today seems like it’s on the mend, and that’s good news for Europe. The government held a bond sale in April, there’s been some progress with getting Greece’s fiscal policy in order. At a huge cost. Unemployment is still high, but it’s falling from 28% earlier this year. There’s a sense that the worst may be over. Let’s talk briefly about Alexis Tsipras, who’s taken a high-profile role as the European Left’s Commission presidential candidate. What happens to Greece and the progress it’s made if he and SYRIZA win the next national elections?

JC: We are not in the dilemma of ‘the drachma or the euro’ anymore. This has gone, and that has to do especially with the guarantee Mr. Draghi has given.

Mr. Tsipras is not the monster as he is described, and he will not have the big majority he needs to rule Greece alone. So all of the steps we’ve seen in the past days are designed to make people anxious, and this is not the right way to handle a democracy…. I, myself, with my new party, the Hellenic European Citizens, we hope that the Greek government won’t stay long because it’s an unacceptable government. Should Mr. Tsipras have a majority, he needs the right partners. He can’t rule alone, and so we need to discuss… unitedly how we can get out of this crisis.

But Mr. Tsipras can’t rule alone, so he’s not a danger for anybody any more.

KL: Data privacy is obviously ann important policy for the next parliament to consider. It’s an issue that has a lot of American policymakers and businesses worried, especially after last week’s Google ruling. Should the EU enact a strengthened data privacy directive? If so, how should it go about balancing data privacy while encouraging technological progress?

JC: The next parliament should continue the line it has taken in the last five years and become even harsher in protecting fundamental civil rights and guaranteeing data protection…. [the current directive] is not sufficient, we need to become more stringent.