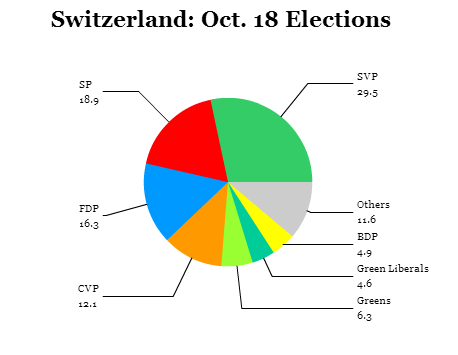

Amid dual concerns about rising immigration and creeping concerns about the reach of the European Union’s writ in non-member Switzerland, today’s Swiss national elections are further evidence of a rightward shift that could complicate governance in a country with a long tradition of consensus-driven government.

![]()

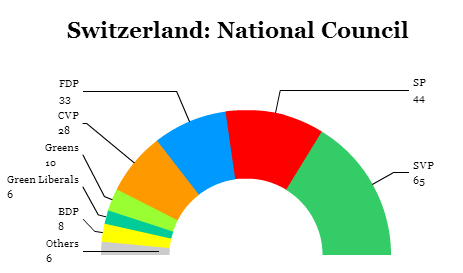

Though Switzerland hasn’t received the deluge of refugees as neighboring Austria and Germany, fears about the largest number of refugees arriving in Europe since World War II, boosted the anti-immigration, right-wing Schweizerische Volkspartei (SVP, Swiss People’s Party), which won a record 65 seats in Switzerland’s 200-member Nationalrat (National Council), the lower house of the bicameral Bern-based Bundesversammlung (Federal Assembly) — more seats than any other single party has won at any election since 1917. Those gains follow the successes of the far-right Freedom Party in two state elections in the past three weeks in neighboring Austria.

When one party wins an election in Switzerland, it doesn’t mean that the party controls government. Instead, under the Swiss ‘concordance’ system, the four major parties of both left and right share membership on the Federal Council, a seven-member executive board that governs Switzerland and that is indirectly elected by the Federal Assembly. Historically, the Federal Council prides itself on collegiality and compromise. The Swiss presidency rotates annually among the seven members, though the presidential role is chiefly ceremonial. Furthermore, there’s no equivalent of a ‘prime minister,’ and the strong regional government of Switzerland’s 26 cantons means that executive power in the country has always been particularly weak, dating to the federal system agreed in 1848.

But Sunday’s result is prompting calls for a Rechtsrutsch — a move from a grand-coalition government to a more clearly right-leaning government on the basis of the SVP’s superior result.

****

RELATED: Swiss immigration vote threatens access to EU single market

****

Both houses of the Federal Assembly will determine the Federal Council’s composition in a secret ballot on December 9. The SVP’s rising strength means that it will take a much more aggressive stand toward shifting the Federal Council to the right, tightening Swiss policy on immigration and the European Union.

In addition to the National Council, Swiss voters were also electing all 46 members of the upper house, the Ständerat (Council of States). Continue reading Anti-migrant mood brings record win for Swiss People’s Party