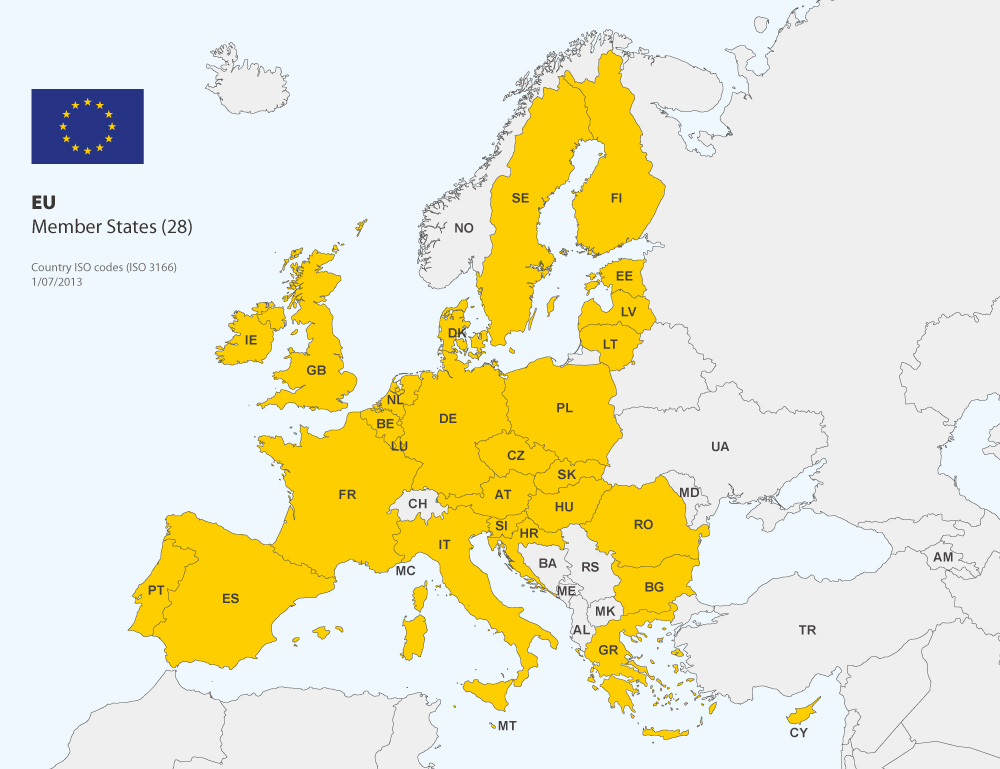

As voters in 28 European countries prepare to head to the polls, beginning on May 22 and running through May 25, no one knows whether Europe’s center-left or center-right will win more seats, and no one knows who will ultimately become the next president of the European Commission.

As voters in 28 European countries prepare to head to the polls, beginning on May 22 and running through May 25, no one knows whether Europe’s center-left or center-right will win more seats, and no one knows who will ultimately become the next president of the European Commission.![]()

But the one thing upon which almost everyone agrees is that Europe’s various eurosceptic parties are set for a huge victory — not enough seats to determine the outcomes of EU legislation and policymaker, perhaps, but enough to form a strong, if disunited, bloc of relatively anti-federalist voices. Voters, chiefly in the United Kingdom, France and Italy, are set to cast strong protest votes that could elect more than 100 eurosceptic MEPs.

In some countries, such as Spain, euroscepticism is still a limited force — the center-left opposition Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) is tied for the lead with the governing center-right Partido Popular (the PP, or the People’s Party) of prime minister Mariano Rajoy. But Spain is quickly becoming an outlier as eurosceptic parties are springing up in places where unionist sentiment once ran strong.

* * * * *

RELATED: In Depth: European parliamentary elections

RELATED: The European parliamentary elections are really four contests

* * * * *

Of course, not all eurosceptics are created equally. Some anti-Europe parties have been around for decades, while others weren’t even in existence at the time of the last elections in 2009. Some are virulently xenophobic, far-right or even neo-Nazi in their outlooks, while others are cognizably on the more mainstream conservative / leftist ideological spectrum. Some seek nothing short of their country’s withdrawal from the European Union altogether, while others seek greater controls on immigration. Some are even pro-Europe in the abstract, but oppose eurozone membership. That’s one of the reasons why eurosceptics have had so much trouble uniting across national lines — the mildest eurosceptic parties abhor the xenophobes, for example.

If everyone acknowledges that eurosceptic parties will do well when the votes are all counted on Sunday, no one knows whether that represents a peak of anti-Europe support, given the still tepid economy and high unemployment across the eurozone, or whether it’s part of a trend that will continue to grow in 2019 and 2024.

With 100 seats or so in the European Parliament, eurosceptics can’t cause very many problems. They can make noise, and they stage protests, but they won’t hold up the EU parliamentary agenda. With 200 or even 250 seats, though, they could cause real damage. There’s no rule that says that eurosceptics can’t one day win the largest block of EP seats, especially so long as most European voters ignore Europe-wide elections or treat them as an opportunity to protest unpopular national government.

For now, though, they’re all bound to cause plenty of trouble for their more mainstream rivals at the national level, and in at least five countries, they could wind up with the largest share of the vote. So it’s still worth paying attention to them.

Without further ado, here are the top 13 eurosceptic parties to keep an eye on as the results are announced on Sunday:

Continue reading A rogues’ gallery of the EU’s top 13 eurosceptic parties