Just days after former prime minister Valdis Dombrovskis was nominated as the European Commission’s vice president for the euro and social dialogue, his successor back home in Latvia is fighting to keep Dombrovskis’s party in power after five tumultuous years.![]()

Laimdota Straujuma, a former civil servant and, until her election as prime minister on January 22, Latvia’s agriculture minister, will attempt to win another mandate on October 4 for the broad center-right coalition government that, in the form of many different parties and combinations, has governed Latvia since its independence in 1993. Dombrovskis’s newly formed party, Vienotība (Unity), the fusion of an alliance of several center-right liberal parties, won Latvia’s October 2010 elections and, though it finished in third place in the most recent September 2011 snap elections, it continues to govern in alliance with three other center-right and populist parties.

If Straujuma (pictured above) is successful, she should send flowers to the Kremlin, because Russia’s newly aggressive tone with respect to its ‘near abroad’ has become a leading factor during the campaign.

When Dombrovskis became prime minister in 2009 amid the global financial crisis, Latvia was facing its worst economic turmoil since the post-Soviet adjustment of the early 1990s. Dombrovskis prevented a devaluation of the lats currency, salvaging Latvian hopes to enter the eurozone (it did in January 2014).

But Dombrovskis’s orthodox economic policy forced budget cuts and a steep internal devaluation and boosted Latvia’s unemployment rate in 2009 to what was then a EU-wide high of 20%, which today rests just above 11%. Though growth has bounced back, Dombrovskis resigned last December after a freak accident in a suburb of Riga, the Latvian capital, when a supermarket roof collapsed and killed 54 people.

In a normal election, with a weary Latvian electorate, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to expect its center-left party to take advantage of years of austerity to form what would be Latvia’s first truly center-left government.

* * * * *

RELATED: Despite risks, Latvia (and all the Baltic states)

still wants to join the eurozone

RELATED: Who is Laimdota Straujuma?

Latvia’s likely first female prime minister

* * * * *

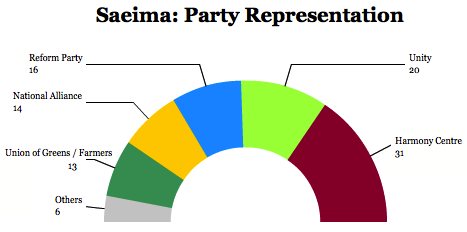

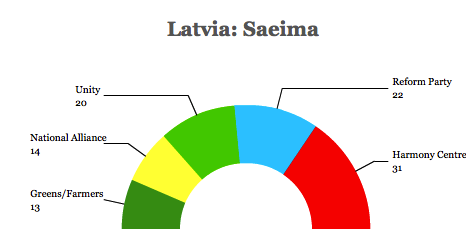

What’s more, Latvia’s center-left party, Sociāldemokrātiskā Partija ‘Saskaņa’ (Social Democratic Party “Harmony,” which previously contested Latvian elections as the wider ‘Harmony Centre’ alliance), was on something on an upswing, winning the largest number of seats in the 2011 elections (31) in the Saeima, the 100-member, unicameral Latvian parliament, and it made even stronger breakthroughs in the 2013 local elections, when Harmony took control of the Riga city council.

But what held Harmony Centre and now, the ‘Harmony’/Social Democratic Party back was its historical role as a party supported mostly by ethnic Russians and Russian speakers. Though Latvia has the largest ethnic Russian population of the three Baltic states (around 26.9%), that’s not a large enough support base to build a majoritarian government. Continue reading Latvian right hopes to ride Russia threat to reelection