There’s no way for the German left to sugarcoat Sunday’s regional election result in North Rhine-Westphalia.

![]()

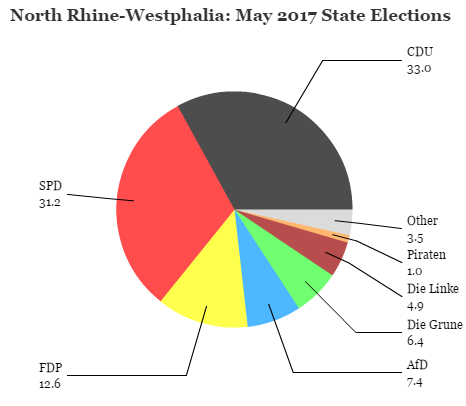

It’s the clearest sign yet that after flirting with Martin Schulz earlier this year, German voters are coming back to Angela Merkel and the center-right Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU, Christian Democratic Union).

North Rhine-Westphalia is Germany’s most populous state, and it’s one of the industrial and technological heartlands of Europe. It’s a relatively left-leaning state — since 1966, the only CDU leader to run the state’s government was Jürgen Rüttgers, from 2005 to 2010. Moreover, it’s the state where Schulz, the SPD’s chancellor candidate for this September’s federal elections, grew up. It’s home to 17.8 million of Germany’s 82 million-plus population. So four months before the national election, NRW has as more predictive power than you might typically expect for a state election, considering that its electorate equals just over one-fifth of the electorate that will decide the national government in September.

It’s too soon to guarantee that Merkel will win a fourth consecutive term, even with the decisive victory last weekend — the third and most important CDU win in three state elections this year. But the result is a clear sign that Schulz’s center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) is struggling to connect with working-class voters who are turning increasingly to alternatives from the anti-immigrant right to the protectionist left to the reassuring stability of the Merkel-era CDU. Indeed, the CDU campaigned throughout the spring on the notion that Merkel and her allies amounted to a ‘safe pair of hands.’ Continue reading Kraft steps down as NRW result gives boost to Merkel’s fourth-term hopes