Winston Churchill is attributed with the quote, ‘Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those others that have been tried.’

But it’s William F. Buckley who said, ‘I am obliged to confess I should sooner live in a society governed by the first two thousand names in the Boston telephone directory than in a society governed by the two thousand faculty members of Harvard University.’

Alex Guerrero, assistant professor of philosophy, medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania (and also a law school classmate of mine), thinks Buckley may have been on to something, and he makes the case for selecting representatives not by elections, but through a lottery system in Aeon today:

First, rather than having a single, generalist legislature such as the United States Congress, the legislative function would be fulfilled by many different single-issue legislatures (each one focusing on, for example, just agriculture or health care). There might be 20 or 25 of these single-issue legislatures, perhaps borrowing existing divisions in legislative committees or administrative agencies: agriculture, commerce and consumer protection, education, energy, health and human services, housing and urban development, immigration, labour, transportation, etc.

These single-issue legislatures would be chosen by lottery from the political jurisdiction, with each single-issue legislature consisting of 300 people. Each person chosen would serve for a three-year term. Terms would be staggered so that each year 100 new people begin, and 100 people finish. All adult citizens in the political jurisdiction would be eligible to be selected. People would not be required to serve if selected, but the financial incentive would be significant, efforts would be made to accommodate family and work schedules, and the civic culture might need to be developed so that serving is seen as a significant civic duty and honour.

At first read, it sounds like a nightmare out of an Arthur Miller play. Three hundred random US citizens would congregate to tackle a discrete issue like climate change, health care reform, or immigration reform.

What’s so bad about democracy?

Before you dismiss the idea outright, it’s important to bear in mind the long, long list of problems with elections, in their current form in the United States and in other mature democracies — and that’s saying nothing about the question of free and fair elections in countries where democratic institutions are less robust. The business of policymaking of a typical 21st century government is typically too complex for direct democracy to thrive in most jurisdictions. The need to become informed about the nuances of even major policy decisions would quickly overwhelm all of us. Experiments with direct democracy, through the proliferation of ballot initiatives to decide key issues, have worked better in some places (Switzerland) than in others (California). The limitations of direct democracy have meant that, outside the classical era of Athenian democracy and a few referendum-driven jurisdictions, ‘democracy’ for most people today means representative democracy. Voters elect legislators and executives on the basis of a plethora of policy positions.

Of course, by gaining efficiency, indirect democracies lose precision — voters will choose one candidate over another for many reasons, and no voter’s policy priorities may line up entirely with any candidate.

Moreover, we can see the other problems of representative democracy in modern US politics. Marketing and advertising, since at least the onset of the television era, can now be more important than policy positions. Accordingly, representatives spend more time today raising money from donors than tending to the business of lawmaking, undermining the one-person-one-vote principle that undergirds representative democracy. As Alex notes, the current process is subject to all sorts of problems. The influence of money and lobbyists can lead to agency and electoral capture. Collective action problems are rife — interest groups who care deeply about an issue can skew policies to their favor, even at the expense of the widely dispersed gains that might otherwise accrue to the rest of the population. Protectionism, tariffs and free trade is a classic example.

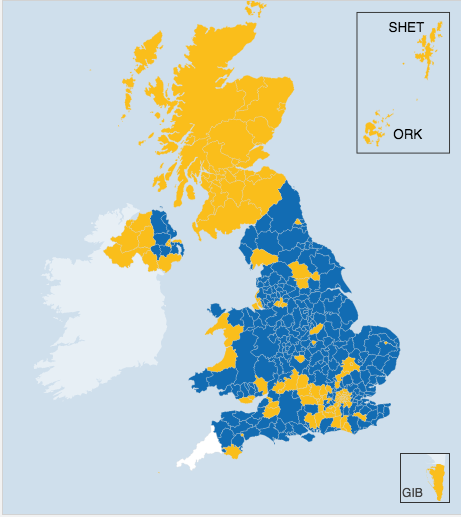

Gerrymandering, barriers to entry and the advantages of incumbency massively reduce competition within the political marketplace. It’s left us with a system where, as Alex writes, ’44 per cent of US Congresspersons have a net worth of more than $1 million; 82 per cent are male; 86 per cent are white, and more than half are lawyers or bankers.’ It’s a system where Congressional reelection rates in the United States routinely exceed 90% — even in a massive ‘wave’ election like the 2010 midterms that saw a Republican wave, the reelection rate was still 85%. Part of that you can blame on gerrymandering, but more so on the natural preferences and geopolitical distribution of urban and rural voters — and perhaps even more so on the US electoral system (i.e., single-member plurality districts instead of proportional representation).

Tradition, financial and political infrastructure, a first-past-the-post electoral system and path dependence mean that, in the United States, two political parties reign supreme. When those two parties agree on policy preferences, it means there’s effectively no competition within the political marketplace on many key issues — in the past three decades, this has included drug legislation, foreign policy, national security, military affairs, gun regulation, financial regulation, home ownership policy and other matters. In many cases, the bipartisan consensus has turned out to be wrong.

Electoral competition, too, is rife with short-term thinking. In a world where public servants are focused on reelection in two years (the US House of Representatives), four years (the US president) or six years (the US Senate), there will always be a temptation to focus on short-term benefits at the expense of long-term costs. Say what you want about the People’s Republic of China, but the governing Chinese Communist Party has to contemplate long-term effects of its policies, because there’s no alternative party to blame. In the US system, Democrats and Republicans can rotate in and out of office and blame each other for perpetuity. Not so in China — the CCP has to own its policy decisions or face a massive popular revolt.

That all assumes, too, that voters make well-informed, rational decisions. As Bryan Caplan argues in The Myth of the Rational Voter: How Democracies Choose Bad Policies, borrowing from the insights of economic theory, ‘democracy’ fails primarily due to irrational and ill-informed voters:

In the naive public-interest view, democracy works because it does what voters want. In the view of most democracy skeptics, it fails because it does not do what voters want. In my view, democracy fails because it does what voters want. In economic jargon, democracy has a built-in externality. An irrational voter does not hurt only himself. He also hurts everyone who is, as a result of his irrationality, more likely to live under misguided policies. Since most of the cost of voter irrationality is external — paid for by other people, why not indulge? If enough voters think this way, socially injurious policies win by popular demand.

It’s also worth asking how truly ‘democratic’ elections have become. Since the 20th century, government has become so complex that many policy decisions are two steps removed from the ballot box, with legislators ceding control to specialized regulators. In the United States, the wide-ranging administrative and regulatory state nearly amounts to a fourth, unelected branch of government. Critics of the European Union have long pointed to a ‘democratic deficit’ within the growing EU institutions. Despite a growing role for the elected European Parliament and perhaps a more representative era in selecting the European Commission, the key decisions of European integration (including the creation of the single market and monetary union) were made more by treaty than at the ballot box.

So should we, therefore, turn to policymaking-by-lottocracy? Continue reading Would ‘lottocracy’ be a better form of government than democracy? →

![]()