On Sunday, Serbians will go to the polls nearly two years before the current government’s term ends.![]()

The results are hardly in doubt.

Prime minister Aleksandar Vučić is basically guaranteed to return to power by a wide margin, according to nearly every poll taken since the last election. His party, the center-right Serbian Progressive Party (SNS, Српска напредна странка), already leads a coalition that enjoys a firm majority in Serbia’s unicameral National Assembly (Народна скупштина).

Originally due by March 2018, Vučić called snap elections in March in a bid to build an even more powerful majority. Vučić argues that a fresh mandate will give his government the space to push Serbia ever closer toward European integration; critics argue that’s a fig leaf to disguise a Vučić power grab, an attempt to squeeze the Serbian political opposition into powerlessness.

Despite problems with self-censorship in the press, Reporters without Borders ranks Serbia 59th in its 2016 press freedom rankings — that’s better than EU members Croatia, Hungary and Italy. Neighboring countries fare far worse — Kosovo ranks 90th, Montenegro ranks 106 and Macedonia ranks 118, just higher than Afghanistan.

With increasingly illiberal figures like Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán thumbing their nose at European Union leaders, Vučić’s rise isn’t without its anxieties.

That’s especially true for the United States and Europe, both of whom have an interest in a country of 7 million that remains, economically and culturally, the anchor of the Balkans region, though Serbia itself shares an alphabet, similar language and a religion with Russia. Serbia is dependent upon Russia for natural gas, as well as a market for exports. In recent years, Vučić has shown that he’s willing to turn to Moscow and other surprising allies, such as the United Arab Emirates, for help when European leaders proved too slow.

That means that the European Union, despite its existential troubles, can’t afford to keep Serbians waiting indefinitely for membership.

Regardless, if polls are correct, Vučić will complete a four-year, three-election cycle that brings the SNS the most powerful domestic government in Serbia’s history following the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

Regionally, the Serbian vote takes place in the context of a year of explosive potential as Macedonia and Montenegro are also set to go to the polls amid tense political climates.

A pathway to Serbian political dominance

In July 2012, the SNS narrowly defeated the center-left, liberal Democratic Party (DS, Демократска странка) by a margin of 24.1% to 22.1%, following eight years of Democratic Party dominance in Serbia that smoothed the country’s transition from war-torn pariah to EU aspirant.

At the same time, Serbia’s two-term president Boris Tadić also lost his office to SNS leader Tomislav Nikolić. Once more sympathetic to Russia than to the rest of Europe, Nikolić and his acolyte, Vučić, quickly embraced the cause of EU accession. They made a deal with the nationalist, center-left Socialist Party of Serbia (Социјалистичка партија Србије / SPS) to take power, even though that meant making the SPS’s leader, Ivica Dačić, once a protégé of strongman Slobodan Milošević (who founded the SPS), Serbia’s new prime minister.

What is past is always present in politics. But that’s especially acute in the case of Serbia, because Nikolić, Vučić and Dačić all began their political lives on the ultranationalist right. Today, however, the three Serbian leaders have (so far, at least) transcended the bitter wars of the 1990s, using the reward of EU accession as a rationale not only to implement IMF-style economic reforms but to make genuine efforts to extradite suspected war criminals from the 1990s and to pacify relations with neighbors, most especially Kosovo, whose independence Serbia does not recognize.

The government performed adequately, however. Neither Nikolić nor Vučić made a harsh turn away from the strong EU relations that the Democratic Party nurtured, nor did Dačić suddenly revert to 1990s era ultranationalism. Dačić led the push to open formal negotiations with the European Union for Serbian accession. However begrudgingly, the Dačić government engaged Kosovo over talks about the breakaway region’s international status.

In early 2014, Vučić, then minister of defense, saw an opportunity for the SNS to take power in its own right, and he essentially forced Dačić to call early elections.

It wasn’t a difficult decision, politically, because it instantly made Vučić the most powerful figure in Serbia.

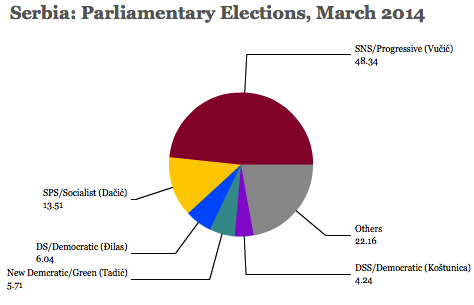

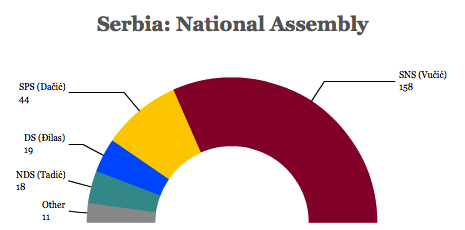

The SNS won easily with 48.4% of the vote and 158 of the 250 seats in the unicameral National Assembly. The second-placed SPS, which would continue in coalition as a junior member, with Dačić serving as Vučić’s new minister of foreign affairs, won 13.5%. The Democratic Party, suffering from a divide between its new leader, former Belgrade mayor Dragan Đilas and Tadić, the future president, who ultimately left to form a new party, the Social Democratic Party (SDS, Социјалдемократска странка). The divide was fatal to Serbia’s democratic center-left, however, because the Democratic Party won just 6.0% and the Tadić-led SDS won just 5.7%.

Bracing for an even larger mandate?

Again, for the next two years, the government performed adequately. Low GDP growth was still strong enough for the unemployment rate to continue declining (though it’s still precariously close to 20%), and Vučić nuzzled ever closer to EU advisors with the hope of advancing negotiations one step closer to EU membership. For now, Vučić hasn’t particularly weakened Serbian democracy on his own, with the kind of anti-liberal steps that Hungary or Poland have taken, though the internal troubles of the opposition may make it seem otherwise. Indeed, Serbia has welcomed refugees in the face of a deluge of Syrians and others on European shores, the largest wave of migrants to Europe since World War II.

Then, at the height of his power, Vučić called fresh elections. Continue reading Vučić set to consolidate political power in Serbia with 3rd consecutive win