The committee awarding the Nobel Peace Prize historically doesn’t shy away from making political statements through its award — and this year was no different.

In retrospect, despite the Western media swoon over 16-year-old Malala Yousafzai, who was shot in the head by the Pakistani Taliban and recovered in the United Kingdom to become a living symbol of the fight for women’s rights in the Muslim world, it makes a lot of sense that the Nobel committee would want to highlight the fight against chemical weapons, given that the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian civil war in August earlier this year was the worst chemical weapons attack since their use in the 1980s by Iraq.

Upholding the international ban on chemical weapons drew a very reluctant US president Barack Obama to the brink of military engagement in the Middle East. In terms of war and peace over the past 12 months, there’s no denying that chemical weapons have playing a tragic starring role:

“The conventions and the work of the OPCW have defined the use of chemical weapons as a taboo under international law,” said Thorbjoern Jagland, the head of the Nobel Peace Prize committee, in announcing the award. “Recent events in Syria, where chemical weapons have again been put to use, have underlined the need to enhance the efforts to do away with such weapons.”

(Honorable mention should go to Denis Mukwege, the Congolese doctor who’s risked his life to fight rape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.)

Even if the Nobel committee’s goal should have been clear in retrospect, it was always going to be a challenge to identify an individual worthy of receiving the award.

Maybe Russian president Vladimir Putin, who took up an offhand comment from US secretary of state John Kerry to broker a United Nations Security Council deal whereby Syria would identify and begin eliminating its chemical weapons stockpiles. But it may have been the US threat of force that pushed Putin to make the offer more than Putin’s natural instinct for peace.

Moreover, Putin presides over an awfully authoritarian state, and his record on press freedom, LGBT rights, civil rights for minorities and the Chechnya conflict hardly screams out ‘Nobel laureate.’ It was always more likely that Alexei Navalny, the crusading opposition figure, would win the prize. Or Lyudmila Alexeyeva, the human rights activist and chair of the Moscow Helsinki Group. Or Lilia Shianova, the director of Golos, Russia’s independent voting rights organization. Or Svetlana Gannushkina, who’s been a leading figure in providing humanitarian and legal aid in Chechnya.

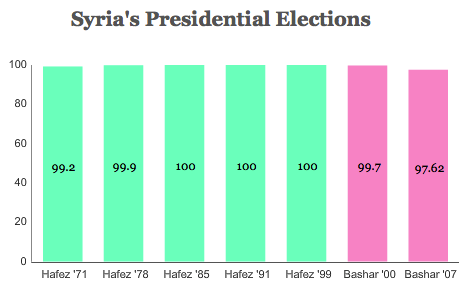

It certainly couldn’t be Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, who’s leading one side of an increasingly intractable civil war and whose regime was responsible for the August sarin attack on the outskirts of Damascus. Despite Assad’s apparent and swift cooperation with chemical weapons inspectors, he’s still engaged in a bloody fight against a mixed force of Sunni rebels and other opponents who want to end his family’s Alawite regime, which has governed Syria with an iron fist since 1971. It also couldn’t be any of Syria’s rebel forces, some of whom are aligned with the most radical Islamist terror networks in the world.

Nor could it be US president Barack Obama, who already won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2009, and his administration’s response to the chemical weapons attack in Syria was bumbling at best. That may be the nature of realpolitik, and the end result is probably beyond what Obama and Kerry ever expected would be possible. But it was hardly a shining moment for US foreign policy.

Moreover, both the United States and Russia have so far failed to destroy their own chemical weapons stockpiles, a fact that the Nobel committee acidly noted in awarding the prize.

So who was left? The chemical weapons inspectors themselves.

Through the process of elimination, the Nobel committee decided to award the prize to the entity whose very job is the elimination of chemical weapons in Syria and throughout the world.

That’s the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (Ahmet Uzumcu, the OPCW’s director-general pictured above), a 16-year-old organization based in The Hague in the Netherlands and the watchdog tasked with keeping the world’s countries in compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention — and which is now playing the crucial role of effecting a deal that should eliminate Syria’s chemical weapons capability by mid-2014, if all goes according to plan. The challenge in Syria represents the most high-profile challenge for the OPCW since its creation but, so far, the OPCW is rising to the task.

Awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to an organization sometimes falls like a wet blanket, even though it’s happened 24 times since 1901. This year’s award follows the decision last year to award the prize to the European Union for its role in becalming the European continent over the past seven decades.

Giving the award to the OPCW instead of Malala (or even Putin or another individual) didn’t necessarily provide a picture-perfect, feel-good catharsis. But it rightly shines a spotlight on an unheralded protagonist at a time when the OPCW’s work is far from complete — even if it succeeds in Syria, the world won’t be rid of chemical weapons.

Photo credit to AFP / Bas Czerwinski.

![]()