In a month when most eyes have been on Germany’s current finance minister, all eyes are now on Germany’s former finance minister, Peer Steinbrück, who is now set to become the main challenger to German chancellor Angela Merkel in federal elections expected later in 2013.

In a bit of a surprise, Steinbrück was named as the candidate of the main opposition party, the center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) on Friday after the other main contender, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, indicated that he didn’t want to run.

Among the trio of Steinmeier, Steinbrück and party leader Sigmar Gabriel, Steinbrück has always been the clear favorite.

But perhaps the most jarring element of Friday’s announcement was that SPD party leaders simply announced the news — in Germany, there are no primaries and no leadership contest as such to determine who will be the candidate for chancellor (essentially, think of the German chancellor much like a very strong prime minister rather than a president). Gabriel is highly unpopular among voters and Steinmeier previously led the SPD against Merkel and her governing Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Party) — to disastrous result.

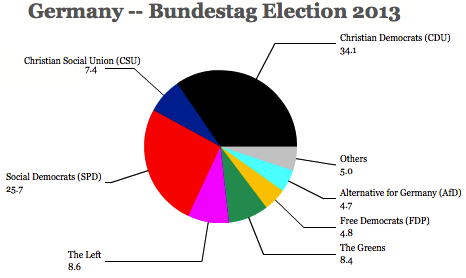

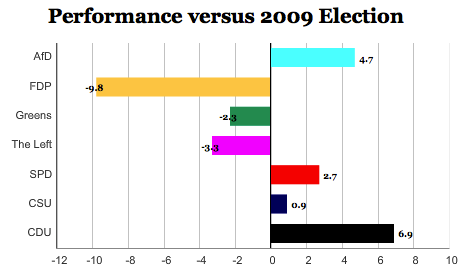

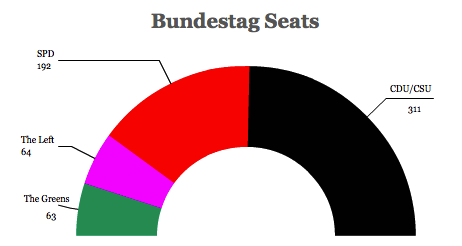

In the previous September 2009 general election, Steinmeier won just 23% for the SDP and lost 76 seats (for a total of just 146). The party thereupon fell out of the CDU-SDP “grand coalition” that had governed Germany since 2005. The CDU, which won 34% and 239 seats, was able to form a more rightist coalition with its preferred partner, the Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), which won 15% and 93 seats. Steinmeier had previously served in the “grand coalition” as foreign minister.

The next federal election in Germany is expected to be held in September or October 2013.

Steinbrück, however, remains a less than ideal candidate — he served as Merkel’s finance minister from 2005 to 2009, so it’s going to be difficult for Steinbrück to draw as clear a contrast on economic policy as might otherwise be the case, even with signs that Germany, the last beacon of economic strength throughout the eurozone, is now also likely headed into recession. As finance minister, Steinbrück famously (demonstrating his, ahem, willful side) derided Keynesian economics and criticized the stimulative approach of the UK’s government under Labour prime minister Gordon Brown, but he is well regarded, alongside Merkel, for steering Germany reasonably well through the 2008-09 financial panic. (Note: Paul Krugman will be happy).

On Europe, too, the German electorate seems receptive to a populist challenge to Merkel’s performance on European affairs — Germans are incredibly weary of four years of what they see as German bailouts of profligate governments from Portugal to Greece. Nonetheless, the SPD is actually more pro-Europe than the CDU — and especially more pro-Europe than the CDU’s sister party in Bavaria, the Christlich-Soziale Union (CSU, Christian Social Union). In Bavaria, the CSU-led government’s finance minister Markus Söder has all but called for Greece to be booted out of the eurozone.

In any event, German voters seem fairly well disposed to giving credit to Merkel for walking a tight line between letting the eurozone crumble, on the one hand, and holding governments in Spain, Ireland, Portugal, Italy and Greece to very tight austerity plans in exchange for European monetary and fiscal support, on the other hand.

The latest polls show the CDU-CSU with a very healthy lead of around 38% to just barely 30% for the SDP — since 2010 and 2011, the gap has only grown wider in favor of the CDU-CSU. The FDP, however, looks set to collapse, picking up just 4%, though the SDP’s preferred coalition partners, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (the Greens) poll a very strong 13%. The newly-formed Piratenpartei Deutschland (Pirate Party) and the more leftist Die Linke (The Left Party) poll 6% each. Given Steinbrück’s centrist characteristics, I would not be surprised to see the current soft support for the Pirate Party migrate to the Left Party or to the Greens — there will be a lot of room on the left in a Merkel-Steinbrück race to win support, both on Europe and on economic policy, especially if Germany’s economy continues in a downward trajectory. Given the Left Party’s strong base of support in the former East Germany, there’s a real opportunity for the Left to break out.

The ideal candidate for the SPD may well have been the premier of Germany’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia, Hannelore Kraft, who led the SPD to a huge victory in elections in May of this year. A premier with charisma, who has championed a more activist state response to boost economic growth, and who could well have been Germany’s second woman as chancellor, Kraft indicated earlier this year that she was not interested in running for chancellor.

![]()