Among the European countries on the 2017 political agenda, Ireland figures relatively low. ![]()

Ostensibly, Ireland may not hold its next general election until 2021. Irish politics have so far avoided the kind of xenophobic, hard-right politics that are roiling larger countries. Nor (other than the republican Sinn Féin) has the country succumbed to the kind of hard-left politics that have emerged in much of southern Europe in the aftermath of the eurozone debt crisis.

But as Enda Kenny, Ireland’s prime minister (known in Ireland as the Taoiseach) prepares to step down after more than six years in power, the country may have its first openly gay leader within weeks.

Leo Varadkar, a 38-year-old rising star and the son of an Indian immigrant (and, like his father, a doctor by trade) who represents the pro-market wing of the liberal, center-right Fine Gael, is now the favorite in the party’s first leadership election in 15 years. First elected to the Dáil (the lower house of the Irish parliament) in 2007, Varadkar immediately joined Kenny’s government in 2011 as transport, tourism and sport minister. From 2014 until last May, he served as health minister, and he currently serves as minister for social protection.

His opponent is the 44-year-old (and openly straight) Simon Coveney, a scion of Irish politics, who got his start in politics at age 26 when, in a 1998, he won a by-election to replace his late father, Hugh Coveney. He has remained a fixture of the Irish parliament (or the European parliament — as an MEP from 2004 to 2007) ever since. Like Varadkar, Coveney has held three ministerial posts in the Kenny era — first as agriculture, food and marine minister, then defence minister, and currently minister for housing, planning, community and local government. Though Coveney is relatively pro-market, he has emphasized the need to combat rising inequality.

Varadkar is the flashier choice, a more radical figure with more panache, while Coveney is viewed as somewhat more wooden, though a policy whiz and a more seasoned official. While they will shy away from actively endorsing Coveney, both Kenny and the current finance minister Michael Noonan are likely to support Coveney.

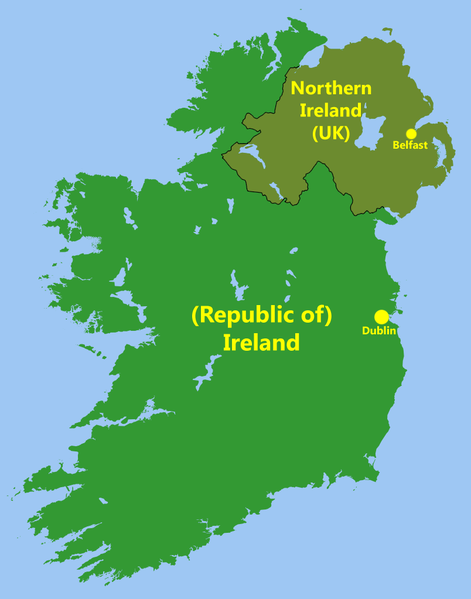

If his lead holds, Varadkar would represent a far greater rupture from Kenny for Fine Gael. He has said he would re-christen Fine Gael as the ‘United Ireland’ Party, and he has promised a series of tax cuts, pledging that Fine Gael would be the party for people who ‘get out of bed early in the morning.’ Among his policy positions is a relatively radical step to reduce the ability of public workers to engage in strikes.

Continue reading In Varadkar, Ireland may be about to have its first openly gay leader