While US president Barack Obama works to convince a skeptical American public and a hesitant US Congress to support military strikes against Syria over a chemical weapons attack last month, Russian president Vladimir Putin showed exactly why he remains such an important world player.

That’s because Putin has apparently convinced Syria to sign the Chemical Weapons Convention, and Syrian president Bashar al-Assad may agree to open his chemical weapons stocks to international supervisors. It’s not a sure thing — Putin wants a commitment from the United States to pull back from the brink of a military strike against Assad within the next week, and US policymakers want a resolution in the United Nations Security Council to demonstrate Moscow’s good faith in resolving the standoff over Syria.

Syrian foreign minister Walid Muallem announced Tuesday that the Syrian regime was willing to open its storage sites and provide access to its chemical weapons:

“We fully support Russia’s initiative concerning chemical weapons in Syria, and we are ready to cooperate. As a part of the plan, we intend to join the Chemical Weapons Convention,” Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Muallem said in an interview with Lebanon-based Al-Maydeen TV.

“We are ready to fulfill our obligations in compliance with this treaty, including through the provision of information about our chemical weapons. We will open our storage sites, and cease production. We are ready to open these facilities to Russia, other countries and the United Nations.”

He added: “We intend to give up chemical weapons altogether.”

It’s a staggering turn of events, and it is likely to slow potential US military action over Syria just a day after US secretary of state John Kerry gave Assad one week to hand over ‘every single bit’ of Syria’s chemical weapons in order to avoid a US-led strike against him in retribution for up to 1,400 deaths in Ghouta and eastern Damascus from what the United States and its allies believe to be a sarin-based chemical attack perpetrated by the Assad regime.

Even if there’s some zero-sum world where Putin ‘wins’ and Obama ‘loses,’ the end result is still a net win for the United States. That’s because, if the Putin deal holds, it’s a result of the Obama administration’s strength — a casebook example where a US president uses the threat of force, not the actual use of force, to bring Russia and Syria to negotiate the terms of a political solution.

The threat of force is perhaps the most effective tool that the United States holds in international affairs because it can accomplish almost all of the goals (or more) of actual use of force while eliminating all of the negative, messy consequences of military force — the cost, the destruction, the risk of civilian deaths, the risk of engendering wider mayhem in the Middle East, the risk of alienating Iran at a time of possible rapprochement under Iran’s new moderate president Hassan Rowhani. Although there’s also a risk that sometimes the United States will have to use actual force in order to make its threat of future force realistic, US governments in the past haven’t exactly shied away from quickly deploying force.

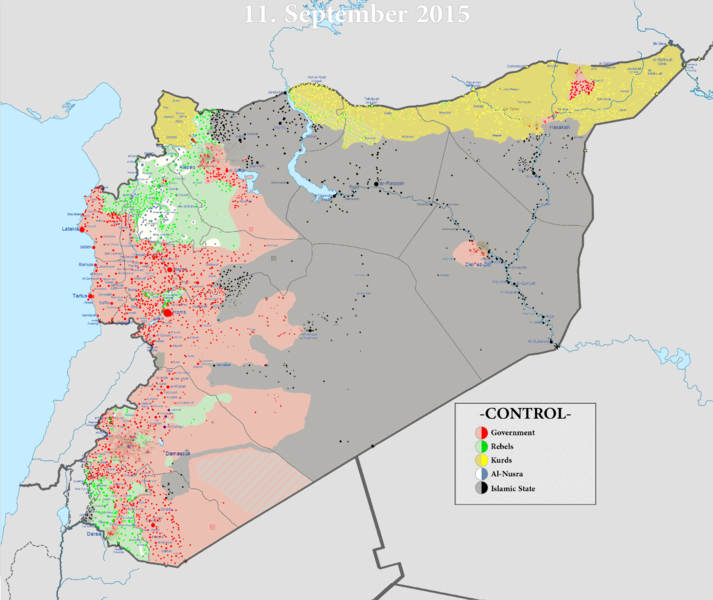

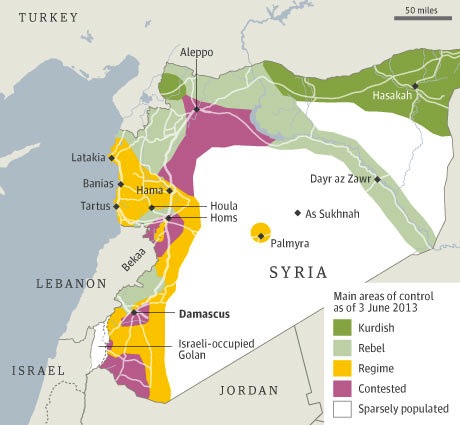

But if the deal holds, and Syria complies with the terms of the international community, presumably through a Security Council resolution (where Russia and the United States, as well as China, France and the United Kingdom hold a veto), it will be a huge win for the effort to reduce the proliferation of chemical weapons in the Middle East — and it will be a more satisfactory result for the Obama administration’s stated goal of strengthening the international norm against chemical weapons. If Assad relinquishes the chemical stocks, it will not only prevent Assad from using them in the future, but also any regime that follows Assad. A glance as the disparate groups that comprise the anti-Assad opposition is enough to tell you that no US administration would be incredibly keen having al-Qaeda sympathizers like the Syrian Islamic Front or the Jabhat al-Nusra, both of which are comprised of radical Sunni Islamists and Salafists, having access to sarin gas, either.

Obama is still scheduled to address the American public tonight on Syria, though the congressional vote is likely to be postponed. The turn comes after Putin and Obama met face-to-face in St. Petersburg, Russia, last week to discuss the Syria crisis. Although the general view late last week was that Obama failed to convince many of his G20 colleagues to support a military strike against Assad, Obama and Putin actually discussed the possibility of an international weapons handover, establishing the conditions for this week’s potential diplomatic solution.

The deal’s terms also come after Charlie Rose conducted an English-language interview with Assad yesterday, during which Assad warned the United States against an attack (and threatened potential consequences to US interests in the Middle East), demanded that the United States provide evidence of Assad’s culpability and refused to accept responsibility for the attack, all while making some fairly nuanced arguments himself against US intervention:

Though US policymakers are right to be initially skeptical of the Putin deal (and it will require a lot of access for UN inspectors to determine that Assad really has relinquished all of his weapons), you can expect hawks like US senator John McCain and other armchair generals to jeer the deal and characterize it as the result of the Obama administration’s weakness. The top story trending at US news website Politico is a vapid piece entitled ‘The United States of weakness’ that purports to designate the US institutions that have ‘lost influence and lost face,’ as if the international crisis in Syria is some mid-semester grade card:

Barack Obama’s unsteady handling of the Syria crisis has been an avert-your-gaze moment in the history of the modern presidency — highlighting his unsettled views and unattractive options in a way that has caused his enemies to cackle and supporters to cringe.

But the spotlight on Obama’s so-far flaccid performance has obscured a larger reality; the Syria episode has revealed the weakness of multiple institutions and would-be leaders in American life.

If Obama and Putin pull of a deal over Syria, though, Obama will have accomplished his long-standing goal of holding the perpetrators of chemical warfare accountable, stabilized Syria no matter the outcome of its two-year-long civil war, demonstrated the will of the US government to use force to stop chemical warfare — all without firing a single missile.

It’s pretty doubtful that the Obama administration had this exact outcome in mind all along — maybe it’s just as likely that he could have set off a chain of events that catalyzes even more Middle Eastern violence. We’ll never know if the Obama administration’s plan from the outset was to rattle the sabers until Putin and Assad agreed to a political settlement, but if so, it’s an incredible job well done — and it answers one of the more baffling questions of the US rush to jump immediately to a military strike against Assad.

I’m still not convinced that the United States even has solid intelligence that Assad is culpable for the attack, especially after reading the US government’s flimsy 1,434-word ‘government assessment’ 10 days ago. While it seems very likely that his regime is responsible, there’s nothing to indicate that Assad ordered the attack or that it wasn’t a rogue element within the pro-Assad ranks. (After all, it bears repeating that Assad had no incentive to use chemical weapons — he was gaining ground in the civil war before August 21 and UN chemical weapons experts were actually in Damascus during the tragedy, hardly the best time to carry off a sarin attack).

While they’re at it, Obama and Putin should join ranks to convince the remaining six countries that aren’t yet signatories to sign up to the Chemical Weapons Convention (or have not yet ratified the convention) — the list includes top US ally Israel, an emergent Burma/Myanmar, Chinese client state North Korea, Angola, Egypt and the newly independent South Sudan.

![]()