It might just be the slogan of the 2016 Republican National Convention.

But it has real meaning. As has been widely reported, Donald Trump’s campaign manager Paul Manafort worked for the former president of Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych, a Russian puppet who ultimately abdicated in 2014 and fled to Russia when even his own supporters couldn’t defend him firing on protestors in Kiev.

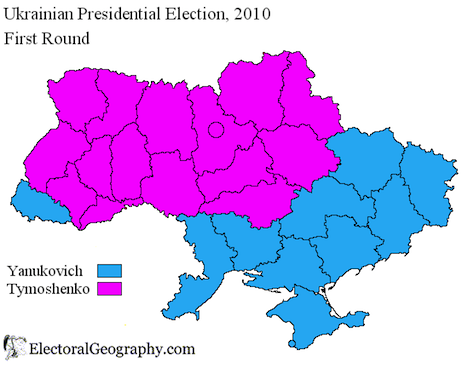

When the pro-Russian clique in Ukraine yelled, “LOCK HER UP” in 2010, after Manafort helped Yanukovych win election, that’s exactly what Ukraine’s new government did. Yanukovych put Yulia Tymoshenko — his 2010 presidential opponent and a former prime minister — in prison. And she spent three years imprisoned, until Yanukovych fled Ukraine and launched the country into a civil war that continues to cripple and divide the one-time Soviet republic to this very day.

Most ironic of all, Tymoshenko’s ostensible crime was for making a natural gas deal as prime minister (under duress) with Russia that Yanukovych, a sycophant of Vladimir Putin, decreed too unfavorable to Ukraine. Even the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Tymoshenko’s jailing was politically motivated.

As I argued in an email earlier tonight to Andrew Sullivan (who’s live-blogging the two conventions for New York Magazine), this is a bad sign for American democracy.

Politicians, and especially presidents, make ethical mistakes. Bill Clinton probably committed perjury about his sex life. Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush were both knee-deep in Iran-Contra. George W. Bush enabled torture and may have fabricated evidence about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq as a pretext for war. Hillary Clinton absolutely disrespected the concept of freedom of information with her email server. Yes, she lied about the emails.

But when I hear an entire political convention yelling “LOCK HER UP,” as a slogan, it’s a troubling sign for American democracy and, let’s say it, the critical thinking of an electorate who would be led by a strongman like Donald Trump and, apparently, New Jersey governor Chris Christie.

I almost wish Clinton would invite Tymoshenko to the Democratic National Convention, just to show Americans how dangerous this moment is in American politics. I know that’s impossible, but Tymoshenko knows something about the abuse of law and being a political prisoner. It was tragic to see it happen in Kiev, but to think that we’re at this point in American politics is frightening.

It’s anything but conservative.

It’s anything but respect for the Constitution.

It’s anything but liberty.