Was Jesse Helms a better chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee than Bob Menendez?

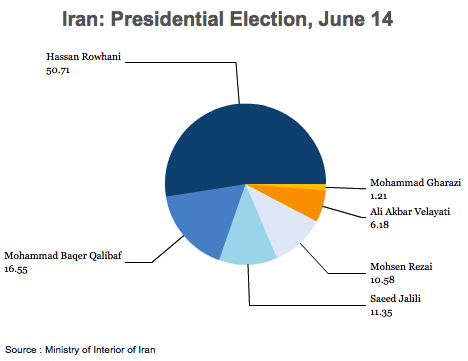

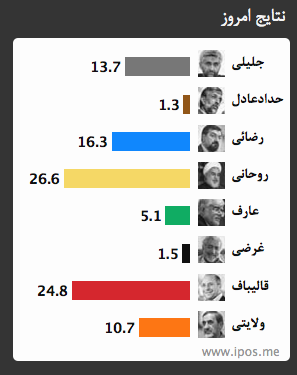

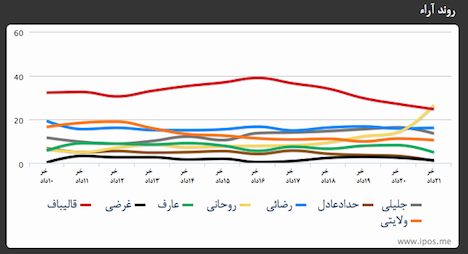

Menendez, who took over the committee earlier this year when former senator John Kerry was appointed as US secretary of state, is making headlines this week for a bill that would largely derail a still delicate US-Iranian rapprochement. He introduced a Senate bill yesterday that, if enacted, would mark a serious setback in the nuclear negotiations between the United States (and the other members of the ‘P5 + 1’ team that includes the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, plus Germany) and Iran. The bill would institute a new round of punitive economic sanctions on Iran on the heels of a six-month deal between negotiators and the administration of Iran’s new moderate president Hassan Rowhani that all parties hope could lead to a more permanent accord. On Thursday, ten Democratic committee chairs sent a letter to Senate majority leader Harry Reid in opposition to Menendez’s bill, and the White House has warned Menendez that his legislative efforts aren’t helping negotiations.

Though Menendez’s bill, co-sponsored with Republican senator Mark Kirk of Illinois, is called the ‘Nuclear Weapon Free Iran Act,’ there’s no firm evidence that Iran even wants to build a nuclear weapon, though plenty of US policymakers suspect that Iran has secret designs on building one. Rowhani and his foreign minister Javad Zarif have disclaimed interest in nuclear weapons, and Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei has argued that nuclear weapons are a violation of Islamic law.

The bill would introduce new sanctions if Iran violates the terms of the current agreement or fails to come to a permanent agreement with the ‘P5 + 1’ team. In essence, it would put an economic sanctions gun to Iran’s head — the bill demonstrates no respect for a process of negotiation between two sovereign states. It seems more designed to score low-hanging political points for conservative Democrats than to engage seriously on finding a mutually acceptable path for Iran’s energy program that also makes the Middle East more stable. Menendez, a longtime ally of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), is siding with Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has attempted to derail the Iran deal at every turn.

As James Traub wrote in Foreign Policy earlier this week:

The reason why Menendez and others really are marching on a path to war is that they are demanding an outcome which Iran manifestly will not accept: zero enrichment. As Daryl Kimball, director of the Arms Control Association, puts it, “This is a strategy based upon hope that is not supported by the evidence of Iranian actions over the past decade, its past statements, or common sense.”….

I have no idea why Menendez and other Democrats believe that more pressure will make Iran abandon a core tenet of the revolution and thus undermine their claim to rule. (I asked for an interview, but the New Jersey senator was not available.) Maybe they believe it because [Netanyahu] has made zero enrichment his own bottom line.

So who is Menendez, and how did he rise to become the preeminent foreign policy official in the legislative branch of US government?

Menendez is the son of Cuban immigrants who came to the United States in 1953 for economic opportunity (not, as you might believe, to flee Fidel Castro, who was in 1953 still six years away from overthrowing the US-supported dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista). Menendez spent his childhood in New Jersey and rose to political prominence in the Democratic machine politics of Union City, which was once known as ’10 Percent City,’ and not because its residents were tithing Christians. Initially a protégé of Union City mayor and New Jersey political powerbroker William Musto, Menendez broke with his mentor only after Musto’s indictment for skimming. Though Musto was ultimately convicted and served five years in prison, he still managed to defeat Menendez when the future senator challenged him for the mayorship in 1982. But Menendez eventually won the office in 1986, then became a member of the New Jersey State Assembly, the New Jersey State Senate and in 1993, a member of the US House of Representatives.

For nearly as long as he’s chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Menendez has been under investigation by a Florida grand jury in connection with potential misconduct with respect to one of Menendez’s top donors, Salomen Melgen, a Miami eye surgeon who moved to Florida from the Dominican Republic in 1980. Though the nastiest rumors about Melgen and Menendez cavorting with underage prostitutes were probably false, Menendez admitted to violating Senate ethics rules when he forgot to reimburse Melgen for two private jet flights to the Dominican Republic in 2010. Other accusations are less salacious but potentially illegal — Menendez is accused of intervening on Melgen’s behalf in respect of a billing dispute between Melgen and the federal government’s Medicare offices and in favor of a port security contract in the Dominican Republic that would have benefitted Melgen financially.

The grand jury hasn’t issued any charges against Menendez, and prosecutors may ultimately choose to drop the matter, but it’s not best practices for the Senate’s top foreign policy voice to be implicated in an abuse of power scandal that involves, in part, international contracts.

The Iran bill follows Menendez’s push earlier this autumn to goad US president Barack Obama into a more hawkish position on Syria that would have seen US military attack on Bashar al-Assad. Menendez actually made the following analogy in his push to win support for an attack earlier this year: Continue reading Why Menendez is such an awful Senate Foreign Relations Committee chair →

Photo credit to AFP / Getty Images.

Photo credit to AFP / Getty Images.![]()

![]()