Since most of the pro-Russian parts of Ukraine are still engaged in a low-grade revolt against Kiev’s pro-Western government, it’s not a surprise that the results of October 26’s snap parliamentary elections were good news for pro-Western parties.![]()

The message of the parliamentary election isn’t quite as awful as ‘Ukraine is doomed,’ but it’s hard to take away a lot of comfort that the troubled country is on the right path to political unity and economic progress.

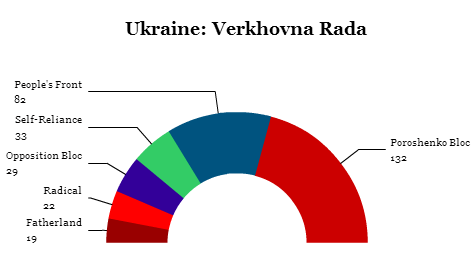

With turnout across eastern Ukraine depressed, most acutely in Donetsk and Luhansk, it makes sense that Ukraine’s new president emerged with the largest number of projected seats in Ukraine’s unicameral parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, after Sunday’s elections.

The Petro Poroshenko Bloc (Блок Петра Порошенка) formalizes the electoral alliance that Poroshenko made prior to the May 25 presidential election with heavyweight boxing champion Vitali Klitschko, who was elected Kiev’s mayor earlier this year.

But the new government of Ukraine will invariably look much like the old one — a coalition between Poroshenko and former prime minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk, whose resignation triggered the snap elections earlier this summer. Then, as now, it’s something of a mystery why new elections were so pressing when Kiev is still struggling to regain control of the eastern regions from pro-Russian separatists.

* * * * *

RELATED: Is Yatsenyuk’s resignation good or bad news for Poroshenko?

RELATED: Can Poroshenko deliver his fairy-tale promises to Ukraine?

* * * * *

Yatsenyuk’s bloc, the People’s Front (Народний фронт), won more absolute votes, according to preliminary results, and another new bloc, Self Reliance (Самопоміч, ‘Samopomich‘), the vehicle of Lviv mayor Andriy Sadovyi emerged as the surprisingly strong third-place winner.

Though some sort of Poroshenko-Yatsenyuk coalition seems the likeliest outcome, the two rivals are already sniping over which bloc should lead the coalition talks. Continue reading Ukraine election results: Unsurprising win for pro-Western parties