Earlier this year, the two undisputed leaders of the pro-Western camp were Yulia Tymoshenko, a former prime minister who had been jailed by the government of then-president Viktor Yanukovych, and Vitali Klitschko, a heavyweight boxing champion who emerged in the 2012 parliamentary elections as the leader of a new reform-minded political party.

Moreover, other capable leaders in anti-Yanukovych movement, including other officials within Tymoshenko’s center-right ‘All Ukrainian Union — Fatherland’ party (Всеукраїнське об’єднання “Батьківщина, Batkivshchyna), such as Oleksandr Turchynov, who ultimately became Ukraine’s acting president, and former foreign minister and economy minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk, who ultimately became Ukraine’s interim prime minister.

So how did a chocolate tycoon with no obvious prior presidential ambitions find his way not only to the top of the polls in Ukraine’s troubled presidential election on May 25, but gather such an overwhelming lead that he could win the race in the first round with over 50% of the vote?

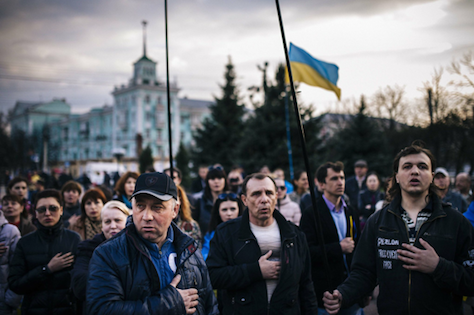

Petro Poroshenko is campaigning on a platform of greater economic ties to the European Union and a pledge to create more jobs. He’s promised to enact the EU association agreement that Yanukovych refused to sign, a decision that led to the anti-Yanukovych protests in Kiev’s Maidan square late last year. He’s also promised to bring an end to the separatist protests in eastern Ukraine, by force if necessary.

Despite this threat, the Kremlin is signaling that Poroshenko is a Ukrainian leader with which Russia can work:

With the country still roiled by separatist violence in the east, the growing air of inevitability around Mr. Poroshenko, who has deep business interests in Russia, has redrawn the Ukraine conflict. It has presented the Kremlin with the prospect of a clear negotiating partner, apparently contributing, officials and analysts say, to a softening in the stance of President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia.

After weeks of threatening an invasion, Mr. Putin now seems to have closed off the possibility of a Crimea-style land grab in the east, and even issued guarded support for the election to go forward.

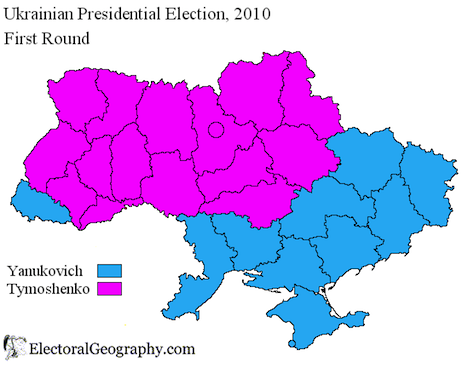

Still, Putin has argued that Ukraine should draft a new constitution that provides for greater federalism before holding new elections. In recent days, he’s urged calm in eastern Ukraine and he even tried to convince separatists to delay the referenda held earlier this month on independence in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. But there’s no guarantee that Putin, who in mid-April referred to Ukraine as ‘Novorossiya,’ or ‘New Russia,’ will recognize the election’s outcome.

* * * * *

RELATED: How the eastern Ukraine referenda

relate to the May 25 election

* * * * *

With no serious contenders, and no real national debate during the election campaign, Poroshenko, who has dodged between both pro-Western and pro-Russian governments for the past two decades, and who has ties to some of the country’s most notoriously corrupt oligarchs, seems to be promising everything to everyone — and polls show he’s going to succeed. He pledges to restore ties with Russia, even while enhancing Ukraine’s economic links with Europe. He will somehow reverse what’s been a near-comical bungling effort by the Ukrainian military to subdue a separatist movement that shows no signs of receding. While doing all this, he will create jobs amid an economic crisis that will require more than $15 billion to $20 billion or more in financial assistance from groups like the International Monetary Fund, which will almost certainly demand in exchange tough budget cuts, tax restructuring, the privatization of many state-owned assets and the liberalization of Ukraine’s economy otherwise, steps that will almost certainly inhibit immediate economic growth that could bring about new jobs in the short-term. All of this in a country that, among the former Soviet nations, has the absolute worst post-Soviet GDP growth rate.

In short, Poroshenko is arguing that he can do what none of Ukraine’s leaders have been able to do for the past two decades at a time when the country is more divided than ever.

Continue reading Can Poroshenko deliver his fairy-tale promises to Ukraine? →

![]()