Depending on your age, your nationality and your perspective, you’ll remember Eduard Shevardnadze, who died three days ago, as either a progressive reformer who, as the Soviet Union’s last foreign minister, helped usher in the period of glasnost and perestroika under Mikhail Gorbachev that ultimately ended the Cold War, or a regressive autocrat who drove Georgia into the ground, left unresolved its internal conflicts, and ultimately found himself tossed out, unloved, by the Georgian people after trying to rig a fraudulent election in a country was so corrupt by his ouster that the capital city, Tbilisi, suffered endemic power outages.![]()

![]()

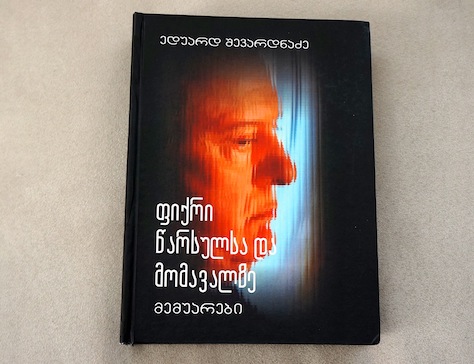

Both are essentially correct, which made Shevardnadze (pictured above) one of the most fascinating among the final generation of Soviet leadership. It’s not just a ‘mixed‘ legacy, as The Moscow Times writes, but a downright schizophrenic legacy.

His 2006 memoirs, ‘Thoughts about the Past and the Future,’ have been sitting on my bookshelf for a few months — I ordered the book from a Ukrainian bookstore, and I hoped to find a Georgian language scholar to help translate them. I would still like to read an English translation someday, because I wonder if his own words might offer clues on how to reconcile Shevardnadze-as-visionary and Shevardnadze-as-tyrant.

Gorbachev and Russian president Vladimir Putin had stronger praise for Shevardnadze than many of his native Georgians:

Gorbachev, who called Shevardnadze his friend, said Monday that he had made “an important contribution to the foreign policy of perestroika and was an ardent supporter of new thinking in world affairs,” Interfax reported. The former Soviet leader also underlined Shevardnadze’s role in putting an end to the Cold War nuclear arms race.

President Vladimir Putin expressed his “deep condolences to [Shevardnadze’s] relatives and loved ones, and to all the people of Georgia,” his spokesman Dmitry Peskov said. Russia’s Foreign Ministry also issued a statement on Shevardnadze’s passing, saying the former Georgian leader had been “directly involved in social and historical processes on a global scale.”

Even Mikheil Saakashvili, who came to power after Georgians ousted Shevardnadze in 2003’s so-called ‘Rose Revolution’ had somewhat generous, if begrudging, words for the former leader: Continue reading Shevardnadze’s legacy to Russia, to Georgia and to the world