On Sunday, voters in Poland, the pivotal country of eastern and central Europe, will almost certainly vote to eject the governing, center-right Platforma Obywatelska (PO, Civic Platform), handing an embarrassing defeat to Donald Tusk, the former prime minister who left Polish politics last year to become the president of the European Council.![]()

With the conservative, nationalist Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS, Law and Justice) set to return to power after eight years, Poland’s rightward move could undermine Tusk’s European role. More importantly, for a country of nearly 39 million people and a rising economic powerhouse in the European Union (with the rising clout to match), it could shift European policy to the right on refugee policy. Ever skeptical of Russia, a new conservative government would also agitate for greater European, US and NATO activism to counter Russian president Vladimir Putin in Ukraine and elsewhere.

May’s presidential vote: prelude to a electoral meltdown

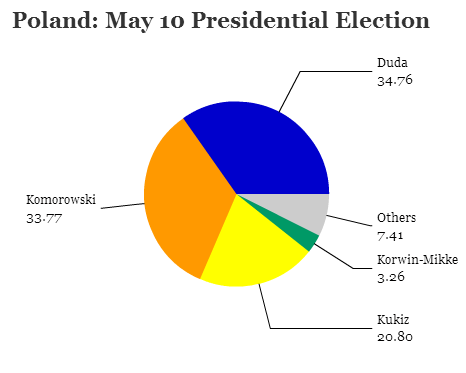

In retrospect, the outcome of the October 25 parliamentary elections seems to have been settled five months ago when Polish voters narrowly ousted incumbent president Bronisław Komorowski in favor of 43-year-old Andrzej Duda, a conservative novice in Polish politics and little-known member of the European Parliament.

Former prime minister Jarosław Kaczyński, a controversial figure on the Polish right, determined earlier this year that he would not seek a rematch against Komorowski, who defeated Kaczyński in 2010 after a tragic airplane crash killed the incumbent, his twin brother Lech Kaczyński, along with dozens of other top Polish officials over Russian airspace. Kaczyński instead, handpicked Duda from relative obscurity to carry the presidential banner.

Komorowski, technically an independent, nevertheless boasted the support of the governing Civic Platform and, until the very end, seemed likely to win reelection. But his wooden style and a lack of engagement did him no favors in a campaign where anti-establishment rage was on the rise. For example, rock singer Paweł Kukiz attracted nearly 21% of the vote as a protest candidate, running an acerbic and populist campaign that won Poland’s youth vote in the first round of the presidential election.

Komorowski fell narrowly behind on May 10 in the race’s first round, and he lost the May 24 runoff to Duda by a margin of 51.55% to 48.55%.

A kinder, gentler Law and Justice Party?

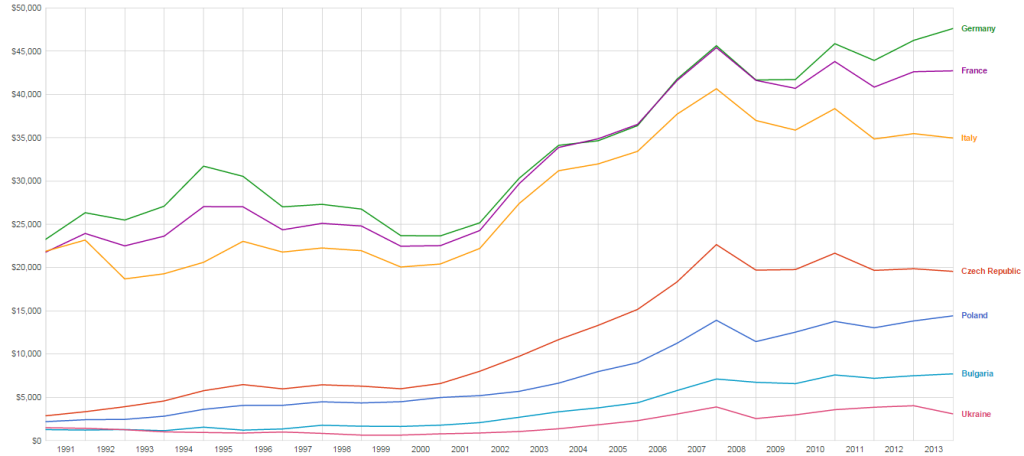

Duda’s outsider status matched a growing sense that Poland’s strong economic performance hasn’t necessarily filtered through to the entire population, especially in Poland’s east, where traditionally conservative voters have missed the boom that’s developed in the country’s west and in urban centers like Warsaw. Moreover, Duda campaigned hard against Poland’s future accession as a eurozone member. Though Poland is notable for achieving the highest growth rate in the European Union since the 2010-11 eurozone sovereign debt crisis — GDP growth peaked at 4.8% in 2011 and achieved an impressive (by European standards) 3.3% growth rate last year — voters are nevertheless in a mood for change.

Kaczyński quickly learned the lesson of Duda’s success, and his party is running the same strategy for the October parliamentary elections. Instead of personally leading the party’s efforts for the parliamentary elections, Kaczyński turned the campaign over to another newcomer, Beata Szydło, a PiS deputy since 2005, the year that the PiS first took power (in a short-lived, two-year government that Jarosław Kaczyński led as prime minister while his brother held the presidency).

At a June party convention, Kaczyński quickly passed the political baton to Szydło, and Law and Justice held a lead in the parliamentary contest ever since. Like Duda, Szydło has taken a softer center-right tone throughout the campaign, avoiding the controversial topics that might otherwise have dogged Kaczyński.

Barring a complete meltdown, it’s nearly certain that Law and Justice will push Civic Platform out of power for the first time in eight years. The latest IBRiS poll, dated October 19, gives Law and Justice 36% of the vote to just 22% for Civic Platform, followed by the Polish left’s electoral coalition with just 11%.

Economic angst and refugee crisis impede Civic Platform’s reelection

Such a damning defeat will leave Tusk somewhat isolated as European Council president and, potentially, in the awkward position of working against Poland’s soon-to-be government, notwithstanding the fact that Tusk’s election was something of an honor for Poland. Befitting the country’s centrality among the set of central and eastern European states that joined the European Union in 2004, Tusk is the first eastern European to hold one of the top EU offices of state.

Tusk left his government in the hands of Ewa Kopacz, a Tusk loyalist, former health minister and former marshal of the Sejm (akin to a parliamentary speaker), who has struggled in the last 13 months in an increasingly Sisyphean attempt to lead Civic Platform to its third consecutive victory. That may have less to do with the amiable Kopacz than a sense of restlessness over eight years of government by a party viewed increasingly as elitist and out of touch. Nagging scandals have emerged in the past two years, the most damaging of which involved the release of secret recordings of former foreign minister Radek Sikorski, former finance minister Jacek Rostowski and others making crude comments, including about the bilateral relationship with the United States, in Sikorski’s case.

As Law and Justice attacks the fits and starts of a Polish economy that still has some wrinkles to work out, Kopacz has been left promising, with little credibility, that young Polish workers can fare just as well at home as in western Europe. Despite growth, Polish nGDP per capita is just around $13,000, far below wealthier countries like Germany and France.

In addition, since the May presidential election, the European migrant crisis is now boosting the Polish right, as the number of refugees across the continent surges to numbers unseen since World War II. In the leaders’ debate on Tuesday evening, Szydło boldly attacked EU refugee policy and argued that ‘Poles have the right to be afraid’ of the unknown consequences of accepting so many refugees. Kopacz, for her part, argued that her government successfully negotiated down the number of refugees that the European Commission’s original quota plan entailed.

Whither Kaczyński?

The former mayor of Brzeszcze, Szydło is virtually unknown outside of Poland (and perhaps even inside Poland until her elevation earlier this summer), which is somewhat staggering for someone who is set to become the leader of the European Union’s sixth-most populous member:

An ethnography graduate and mother to two sons, the erstwhile PiS backbencher was only recently as unknown as Duda. But she has a reputation for being well-adjusted, hard-working and resilient. But also a little dull…. She doesn’t have to pretend to be down-to-earth — she just is.

Though Kaczyński himself formally nominated Szydło as the Law and Justice prime ministerial candidate, the party founder will surely play an important behind-the-scenes role if the PiS returns to power. So the largest question mark hanging over the coming PiS government is just how much it will be Szydło’s government and not just Kaczyński’s government. Last week, for example, Kaczyński made headlines by suggesting that migrants are bringing ‘all sorts of parasites and protozoa’ to Europe.

For all of Kaczyński’s odd statements, he may turn out to be more distraction than puppetmaster. Duda, for example, has taken a much friendlier line towards Germany than Kaczyński might have liked, and Szydło would be wise to follow Duda in avoiding the confrontational approach with European leaders that Kaczyński deployed a decade ago. Nevertheless, Poland will certainly continue to take a hawkish line against Russia, pushing for greater EU and NATO engagement over Ukraine and the former Soviet Union.

Poland’s voters will elect all 460 deputies of the Sejm, the lower house of the Polish parliament, and all 100 senators of the upper house, the Senat. The deputies are elected by proportional representation in multi-member constituencies that contain between 7 and 19 representatives, subject in each case to a 5% national threshold. (Senators are elected on a first-past-the-post basis).

For a decade, Polish politics has been a contest between two visions of the ‘right’ — Tusk’s liberal, business-friendly and pro-European variant and Kaczyński’s socially conservative, religious, populist and eurosceptic version. That will remain the case on Sunday, though there are a handful of other parties vying for seats, a handful of which are new to the political scene.

The traditional party of the Polish left, the Democratic Left Alliance, joined forces with four other smaller leftist, centrist and green parties to form the Zjednoczona Lewica (ZL, United Left), under the leadership of Barbara Nowacka. The parties together won 18.8% of the vote in the 2011 election, but polls suggest it will be lucky to win barely 10% in 2015. Though the party boldly advocates taking in as many Syrian and other refugees as possible, the Polish left has long been out of sync with the electorate.

Kukiz, whose own anti-establishment movement took the presidential campaign by storm, seems to have stalled, with support for his ‘Kukiz ’15’ movement fizzling gradually since May, though the group may still win some seats in the Sejm.

The longstanding Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe (Polish People’s Party), a traditional Christian democratic party, and the more libertarian, anti-immigration and anti-European ‘KORWIN’ coalition of the hard-right MEP Janusz Korwin-Mikke could also enter the Sejm. Nowoczesna (Modern), a liberal party formed in May by economist Ryszard Petru, is also hoping to cross the 5% threshold.

If all three parties make it — and if Law and Justice fails to win a 231-seat majority, a distinct possibility — Szydło might be forced to include one of them as a partner in a governing coalition.