Pity poor Bulgaria. It has the lowest GDP per capita of the entire European Union (around $7,300). It has lost over 19% of its population from its 1988 peak. It is now struggling through the latest European financial crisis with a series of revolving governments, low economic growth and an unemployment rate that today is still over 11%.![]()

So when Bulgarians voted on Sunday to elect yet another government, they did do so with the same kind of ennui that’s marked so many of the country’s recent, frequent elections and a sense of hopelessness as the country’s youngest, brightest minds look to Germany, London and elsewhere for work.

Boyko Borissov (pictured above), a former center-right prime minister between 2009 and May 2013, is set to return to the office he once held, following a technocratic, center-left government headed by former finance minister Plamen Oresharski that fell in August. Bulgaria has since been governed by another caretaker, Georgi Bliznashki, who warned that Bulgaria’s next government needs to be strong enough to carry through major reforms to pull the country out of its ‘post-communist swamp.’

Borissov is the leader of the Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB, Граждани за европейско развитие на България), and his main opponent is the Coalition for Bulgaria (Коалиция за България), which is essentially a wider version of the center-left. Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP, Българска социалистическа партия).

The Bulgarian Socialists won enough seats in the last election in May to form a governing coalition with the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS, Движение за права и свободи), a liberal party that represents ethnic Turks and other Muslims.

Among the mounting problems that the government faced was the collapse of Bulgaria’s fourth-largest bank earlier this summer, Corporate Commercial Bank, which froze the accounts of 200,000 Bulgarians. Protests against the government last year failed to result in any substantive change.

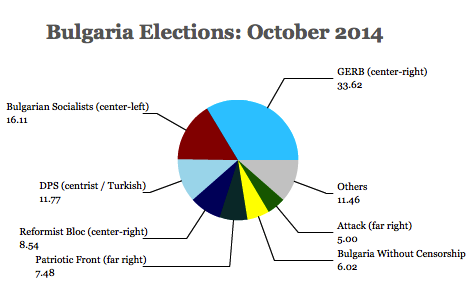

This time around, however, they fell far lower, as GERB seemed headed to a clear victory. With just over 42% of the vote counted early Monday morning, GERB led by a margin of over two-to-one:

Bulgarians voted Sunday to elect all 240 members of the unicameral National Assembly (Народно събрание), and early results indicated that four new groups would enter the parliament, doubling the number of parties from four to eight.

In fourth place, however, is a potential coalition partner for GERB, the Reformist Bloc (Реформаторски блок), formed in December 2013 as a liberal electoral bloc that, like GERB, lies on the center-right, that won attention in May’s European parliamentary elections when it won one of Bulgaria’s seats. Together, GERB and the Reformist bloc will hold nearly 45% of the seats in the National Assembly, depending on whether another small group, the Alternative for Bulgarian Development, remains above the 4% threshold needed for winning seats.

That means that Bulgaria’s next government is unlikely to be strong enough to effect the kind of massive reforms that could transform policy on a scale sufficient to stop the country’s economic, cultural and demographic hemorrhaging.

Though the Bulgarian Socialists were devastated after their failed government, their chief coalition partners, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS, Движение за права и свободи), a centrist group that defends the interests of Bulgaria’s Turkish ethnic minority (around 9% of the population) and its Muslim religious minority (around 8% of the population), largely held onto its voter base.

The fourth existing group in the National Assembly, the far-right Атака (Attack) was set to lose support, falling from 7.3% in the 2013 election to 5% or so in 2014. But the number of far-right and populist legislators is set to rise, because another nationalist party, the Patriotic Front (Патриотичен фронт), formed only two months ago was winning around 7.5%, itself formerly part of a the populist Bulgaria Without Censorship (BBT, България без цензура), which was formed in just January 2014, and which was winning another 6% of the vote.

One of the most important decisions that Borissov’s presumptive government will have to make is whether to proceed with the South Stream gas pipeline, which is planned to run through the Black Sea and through Bulgaria to the Balkans, Austria and Hungary. It’s a project that Russian officials maintained over the weekend would move forward regardless of Bulgaria’s next government, despite EU hesitation about its member-states becoming even more reliant upon Russia for energy.

While Borissov and GERB have been skeptical about the project, and Borissov has said that he will follow the EU’s lead on South Stream, the pipeline could bring precious capital and additional energy resources to Bulgaria. Higher utility prices were one of the reasons for the 2013 anti-government protests, so it could be difficult for Borissov to reject the development. Oresharski reluctantly halted progress in June over EU competition law concerns.

Thanks, Kevin. One indication of the poor Bulgarians’ fecklessness came to me thanks to Boyko Vassilev in Transitions Online: A year ago, as you mentioned, the popular consensus was that electricity tariffs had to fall; now, after the near-collapse of the National Electricity Company under massive debt, almost everyone accepts that tariffs need to rise. Oops.