Photo credit to Grigory Dukor / Reuters.

Photo credit to Grigory Dukor / Reuters.

Last week, with the world’s attention on the NATO summit and Ukraine, Russian president Vladimir Putin made some eyebrow-raising comments about Kazakhstan, the sprawling Central Asian country that straddles Russia, China and other former Soviet republics.![]()

Just days after meeting with Kazakhstan’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev (pictured above, left, with Putin), who joined the Minsk summit that brokered last week’s ceasefire between the Ukrainian central government and pro-Russian rebels, Putin fielded a question about Kazakhstan from an audience member at an youth forum in Russia:

“He created a state in a territory that had never had a state before,” Putin said during the Aug. 29 visit, according to a Kremlin transcript. “The Kazakhs never had any statehood. He created it.”

Putin’s comments caused a stir in Kazakhstan, a former Soviet republic of 17.9 million people, which has emerged as the largest economy of central Asia.

Many Kazakhstanis are worried that Russia’s newly muscular stand with respect to its ‘near-abroad,’ especially as it concerns ethnic Russians outside Russia, could mean trouble for the country in the future. Having won its independence in 1991 with the breakup of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan’s leaders have watched the current conflict between Russia and Ukraine warily, especially after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March.

Nearly 23.7% of Kazakhstan’s citizens are ethnic Russians (compared to 63.1% Kazakh, 2.9% Uzbek, 2.1% Ukrainian, 1.4% Uighur and 1.3% Tatar). Many of them are concentrated in northern Kazakhstan, and there’s a fair share of speculation that one of the purposes of Nazarbayev’s decision to move the capital of Kazakhstan from Almaty, still the country’s largest city and its financial and cultural capital, to Astana, farther to the north, is to create a bulwark against Russia.

Notwithstanding Putin’s comments, there’s been a Kazakh national identity since at least the end of the 15th century, when a united Kazakh khanate emerged. Over the years, however, the khanate splintered and by the 17th century, the lands of today’s Kazakhstan came under control of the Russian empire.

Though a Kazakh state existed briefly between 1917 and 1920, it quickly became a Soviet Socialist Republic, and the Kazakhs took more than their share of abuse at the hands of Soviet officials throughout the 20th century. Many Kazakhs were forced to serve in gulags, many of which were established in what is today northern Kazakhstan. Eastern Kazakhstan’s Semipalatinsk became the chief nuclear weapons testing site in the Soviet Union, which led to massive radiation exposure among local residents.

That’s one of the reasons Nazarbayev quickly gave up his country’s nuclear arsenal when he returned over 1,200 nuclear warheads to Russia in the early 1990s and destroying Semipalatinsk. Kazakhstan, in the course of less than a decade, went from being the country with the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal to being a nuclear-free country and a case study in effective non-proliferation, even though Kazakhstan remains the world’s largest exporter of uranium. Nazarbayev’s stand on nuclear non-proliferation, and his cooperation with US military goals in Afghanistan and central Asia, are one of the reasons that he’s won so much popularity in Washington over the years.

But if Putin’s grasp of Kazakh nationalism was somewhat dodgy, his comments were felt so ominously in Kazakhstan because of the skill with which Nazarbayev has guided Kazakhstan since the Soviet era. Putin is essentially correct that no one is more fundamental to Kazakhstan’s national identity and independence today than Nazarbayev. With no clear successor — or process for succession — in sight, the obvious worry is that Putin and/or Russia could fill any power gap when Nazarbayev dies or leaves office.

Nazarbayev, now age 74, worked his way up the Communist Party during the Soviet era. He became First Secretary of the Kazakhstan SSR in 1989 and was offered the Soviet vice presidency by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990. After independence, Nazarbayev quickly consolidated power and won the country’s first presidential election with over 91% of the vote. He’s been winning reelection ever since — in 1999, in 2005 and most recently in 2011, when he was reelected with 95.55% of the vote. Though he demurred from a proposed referendum to extend his term to 2020, Nazarbayev’s power is essentially unchallenged, and his party, the Nur Otan (Нұр Отан, Light of Fatherland) controls 83 of 98 seats in the Majilis (Мәжіліс), the lower house of Kazakhstan’s rubber-stamp parliament.

Though democracy isn’t necessarily well-rooted in Kazakhstan and though opposition forces aren’t well-established, Nazarbayev has developed massive and truly genuine popular support as the father of Kazakhstani independence and due to the economic growth over which he’s presided in nearly a quarter-century of leadership.

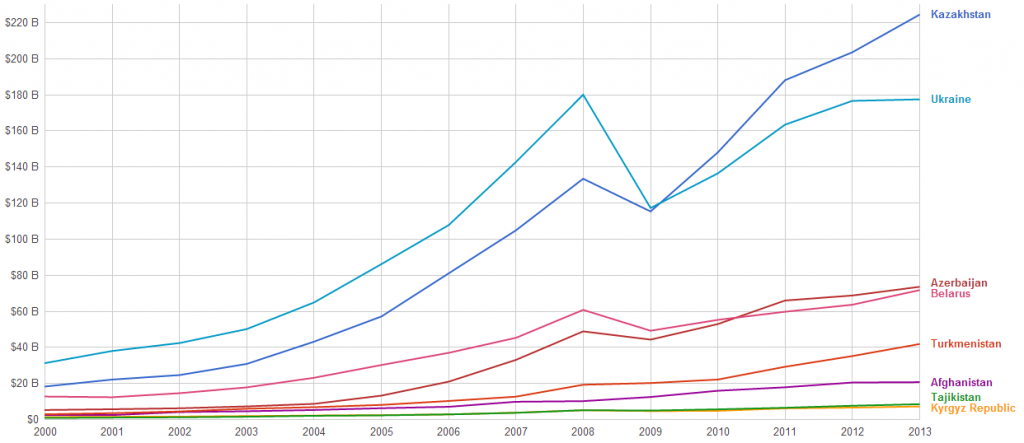

Since 2000, the development of Kazakhstan’s oil and gas industry has given it, easily, the strongest growth of any economy in central Asia — or even among the former Soviet republics:

Nazarbayev was merely a prime minister of the Kazakh SSR in the 1980s when oil reserves were first discovered. Today, Kazakhstan pumps more than 1.6 million barrels of oil a day, and it has over 30 billion barrels in reserve. That oil, along with natural gas wealth, has resulted in a massive rise in incomes, employment, welfare and education. Today, the country’s GDP per capita is nearly $12,500 — and rising. Under the ‘Kazakhstan 2050’ strategy that Nazarbayev announced in his December 2012 state of the nation address, he seeks to bring the country within the world’s top 30 economies within the next 35 years and otherwise diversify the country’s economy to supplement its dependence on the oil and gas industries.

Though, along with Belarus, Kazakhstan will be a founding member of Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union, Nazarbayev has cautioned that he doesn’t see the EEU as a political union, but merely an economic one:

“Kazakhstan has a right to withdraw from the Eurasian Economic Union,” Nazarbayev told his country’s Khabar television, according to remarks cited by Kazakhstan’s Tengri News on Wednesday. “Kazakhstan will not be part of organizations that pose a threat to our independence.”

“Our independence is our dearest treasure, which our grandfathers fought for,” Nazarbayev was quoted as saying. “First of all, we will never surrender it to someone, and secondly, we will do our best to protect it.”

For more than a decade, Kazakhstan has pursued what it calls a ‘multi-vector’ foreign policy. That’s code for the fact that Nazarbayev and his advisors seek to triangulate (or quadrangular) Kazakhstan among world powers like Russia and China, both of which are neighbors, and the United States, which has developed closer ties with Kazakhstan in the past two decades due to US-based oil exploration in the private sector and more strategic cooperation in US efforts to target radical Islamic terrorists. With the war winding down in Afghanistan, to Kazakhstan’s south, there’s some fear that the United States could lose strategic interest in Kazakhstan, specifically, and central Asia, generally.

The completion of the Kazakh-China oil pipeline in 2005, Central Asia’s first such pipeline to the People’s Republic of China, has boosted trade ties between the two countries. Today, 21% of Kazakhstan’s exports flow to China, while only around 10% flow to Russia — barely more than the 9.3% sent to France. (The Kazakh pipeline is one reason nationalist attacks in Xinjiang worry Beijing so much).

But it’s easy to see how Kazakhstan, with reduced strategic importance to the United States, could easily become vulnerable to Russian aggression in the post-Nazarbayev era.

The next presidential election will take place in 2016, and Nazarbayev is expected to stand. But there’s no process for determining who will succeed Nazarbayev. He recently restored Karis Massimov, a charismatic former prime minister, to the premiership in April 2014. At age 49, Massimov already served as prime minister between 2007 and 2012 before being named as Nazarbayev’s chief of staff. He won strong marks from the international investment community for his stewardship of the Kazakhstani economy during the global financial crisis, and Massimov might be expected play a strong role in Kazakh affairs for decades to come. He is said to be close to Nazarbayev’s son-in-law, Timur Kulibayev.

But without a firm plan for succession — or a sudden vacuum in power if something happens to Nazarbayev — Putin could easily take advantage of the chaos to build a stronger military influence in northern Kazakhstan, or even annex some of the Russian-majority cities in the north.