Washington may be enjoying some well-deserved rest from the brinksmanship of the dual crises over the US federal government shutdown and the possibility that the US Congress might not raise the debt ceiling.

Though both crises ended last week, a new crisis may have been gathering steam while the world focused on the global implications of a seemingly dysfunctional American political system.

It’s Puerto Rico, where both finances and the economy seem to be spiraling out of control.

Bondholders are pressuring Puerto Rico

Investment vehicles that buy state and municipal bonds have long loved Puerto Rico’s bonds. Although the bonds are rated BBB+ (by Standard and Poor’s), they are a tax-exempt hat trick. Not only are Puerto Rican bonds exempt from all federal taxes (like all state and municipal bonds), and not only are they exempt from applicable Puerto Rican commonwealth and other local taxes (which is generally how most state and municipal bonds are treated in the state or territory of their issuance), Puerto Rican bonds are exempt from state taxes in all 50 US states. So while Virginian bonds may be taxable under New York state tax, or Californian bonds may be taxable under North Carolina state tax, Puerto Rico’s bonds are exempt from state and local taxes everywhere.

Bondholders have typically shrugged away Puerto Rico’s ‘BBB+’ rating because the yields were sufficiently high enough (around 5%) and the tax advantages so pronounced that Puerto Rican debt looked like an easy way to goose returns for the average fund manager. So Puerto Rican bonds became predictably popular, and many mutual funds and other investment vehicles are widely exposed to Puerto Rican debt. Morningstar estimates that 77% of all muni funds hold Puerto Rican bonds to some degree, and they’re all now incredibly itchy about their exposure.

But when yields started climbing over the summer and early autumn to above 8% and even 9%, it spread alarm not only in San Juan, but in New York and other global financial capitals, as investors and analysts started thinking more deeply about the weakest geographic link in the US financial system, a ‘commonwealth’ with a much more fragile economic outlook that shares only some elements in common with the mainstream US economy. Puerto Rico’s governor, Alejandro Garcia Padilla, and a slew of top officials have spent the rest of October in New York, Washington and elsewhere trying to calm markets and policymakers.

No US state has a debt outlook as poor as Puerto Rico’s, and its ‘BBB+’ rating is just one notch above junk debt status. If any of the three major ratings agencies downgrade Puerto Rican debt further, it could trigger a number of adverse ‘death spiral’ consequences. Puerto Rican bonds are already selling on the open market well below par, but if Puerto Rican debt hits ‘junk bond’ status, it would suddenly become much, much worse.

Mutual funds could be forced to sell their entire Puerto Rican portfolios, which would flood the market with bonds that would become almost immediately worthless. Puerto Rico’s government could be forced to post additional collateral against those bonds, leaving its government even more strapped for cash. That’s not even taking into account the effects of any credit default swaps related to Puerto Rican debt.

All of which means Puerto Rico is now a lot closer to insolvency than it was a month ago.

But unlike the city of Detroit, which filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy earlier this summer, Puerto Rico is a sovereign (technically an ‘unincorporated territory’) and cannot file for bankruptcy as a matter of law. To the extent there was any legal doubt about it, a federal court slammed shut the door in 2012 when it ruled that the pension fund of the commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands could not file for bankruptcy.

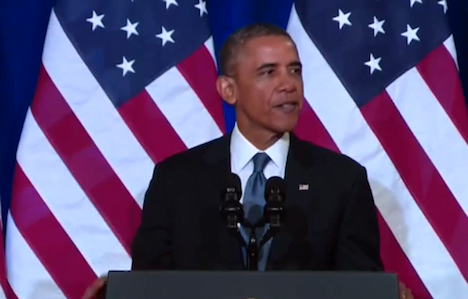

That leaves US president Barack Obama with the unpalatable option of having to consider a bailout of Puerto Rico — an option that some Puerto Rican officials were already discussing openly earlier this month:

In a meeting with bond analysts in New York on Monday, the president of the Puerto Rican Senate, Eduardo Bhatia, said officials in the United States Treasury and White House had been analyzing the situation carefully, “wondering how they can help Puerto Rico send a very strong signal of stability right now.”

Given that the Republicans who control the US House of Representatives are incredibly anti-debt, the fight to raise the debt ceiling would look like a cakewalk compared to the congressional fight over a potential Puerto Rican bailout. If House Republicans seem unwilling to move forward on immigration reform, they seem even less likely to approve a bailout for a territory that pays no federal income tax, that elects no members to Congress and that has no electoral votes in the US presidential election.

Is Puerto Rico the Greece of North America?

The real horrorshow element to this is that Puerto Rico could wind up being to the United States what Greece was to the European Union — the canary in the coal mine that exposes wider state-level and municipal exposure.

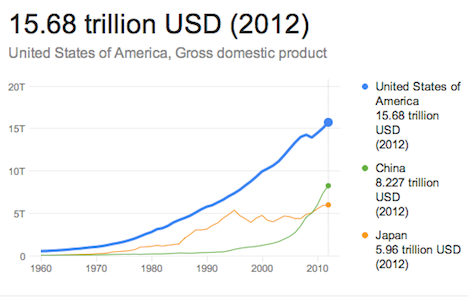

The immediate possibility of a US debt default through political brinksmanship has now passed, at least until February 2014. Furthermore, no one expects Puerto Rico to fall out of the ‘dollarzone,’ or face the idiosyncratic problems that the European Union faces, where monetary policy is set at the European level and fiscal policy is still set at the national level.

But if yields remain elevated, Puerto Rico won’t be able to borrow enough to finance its government. Its leaders say that Puerto Rico is prepared to refrain from further borrowing through June 30 of next year and wait out the current debt scare, but that’s hardly a solution to the crisis. Even if that estimate is correct, what happens in July 2014 if yields spike again? What happens the next time bondholders start doubting Puerto Rico’s ability to meet its debt obligations?

Like Greece, Puerto Rico spent the 2000s on a debt spree — its debt load as a percentage of what Puerto Rican GNP increased from around 60% in 2000 to over 100% today.

It now seems clear that Greek debt was mispriced following its entry into the eurozone because debt yields converged among all eurozone countries. That allowed Greece’s government to borrow throughout the 2000s at rates lower than its fundamental economic and financial performance would otherwise warrant. Essentially, Greece continued to borrow at Greece-level amounts but with the benefit of German-level rates.

In the same way, investors have potentially mispriced Puerto Rican debt — no one actually treated Puerto Rico’s bonds as if they were one downgrade away from junk status. That’s partly because the tax incentives were so favorable, but it’s also because no one really thought that the debt of a US territory was actually so risky.

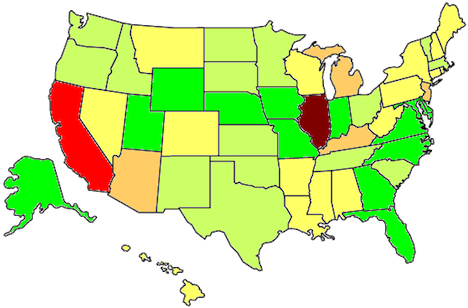

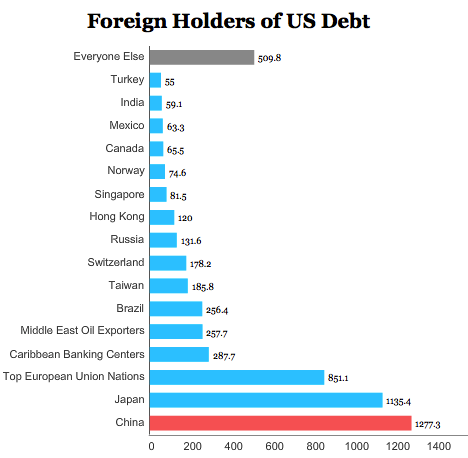

But the debt ceiling fight highlighted the attention of world markets on the precariousness of US debt generally. So while a run on Puerto Rico’s debt could end with Puerto Rico, it could also make mutual funds and global investors think twice about holding US municipal and state debt, especially in the wake of the debt ceiling fight and Detroit’s municipal bankruptcy. There’s wide variance among the credit ratings of the 50 US states:

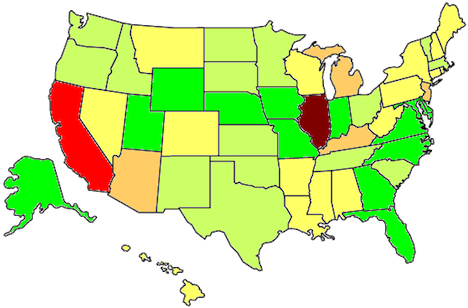

According to S&P state-level credit ratings (as of January 31), while many US states have stellar credit ratings of ‘AAA’ (bright green in the map above) or ‘AA+’ (spring green), there are plenty of states with ‘AA’ (yellow) or ‘AA-‘ (orange).

Two of the largest states with a combined population of nearly 51 million have even more precarious ratings — California (rated ‘A’), despite the best efforts of California governor Jerry Brown to transform his state’s finances, and Illinois (rated ‘A-‘). State debt loads vary considerably on a per-capita basis as well — this chart from the Tax Foundation shows that per-capita state-level debt ranges from $925 in Tennessee to over $11,000 in Massachusetts.

But it’s all worse in Puerto Rico, which has issued about $87 billion in outstanding debt, which comes out to over $23,000 on a per-capita basis.

Puerto Rico’s economy has been struggling for a decade

Meanwhile, no US state has an economy that’s in such poor shape as Puerto Rico does.

Puerto Rico’s unemployment rate is 13.9% (as of August), which is higher than the national average (7.3%) and higher than any other US state or territory.

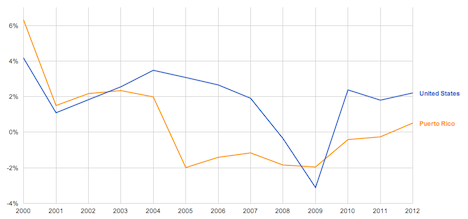

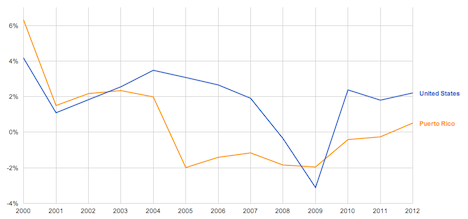

Like Portugal and Italy, Puerto Rico’s economy was stagnant long before the 2008-09 global financial crisis — since the year 2000 (when it achieved 6.3% GDP growth), the Puerto Rican economy has been in contraction more often than it’s been in expansion. Here’s a chart of the GDP growth of Puerto Rico against that of the United States between 1999 and 2012 — you can see that Puerto Rico entered a recession in 2005 that ended only last year, when it posted 0.5% growth:

Puerto Rico’s economy outperformed the US economy only once in the past decade — it didn’t take the sharp hit that the United States suffered in 2008 and 2009. But even that’s bad news for Puerto Rico, because it shows just how disconnected the island’s economy is from the mainstream US and global economy.

Moreover, Puerto Rico is already starting off far behind the US mainland in just about every economic indicator. Its median income of around $18,000 is far lower than the average income in the United States, and it’s about one-half of the poorest state median income (Mississippi’s median is around $36,000). Nearly 41% of Puerto Ricans live below the poverty line, compared to just 16% within the United States. Its regional GDP per capita is around $27,000, about half that of the United States generally.

Also like Portugal and the peripheral economies of Europe, Puerto Rico’s population (around 3.67 million) is in decline. Its population peaked at just over 3.8 million people in 2004, and it’s dropped more than 4% in the past eight years, partly due to migration to the US mainland and partly due to a declining birthrate. Just as in the peripheral economies of Europe, population decline means that there are fewer workers to support an increasingly unproductive and aging population.

Continue reading The next debt crisis in the United States may require a Puerto Rico bailout →

![]()