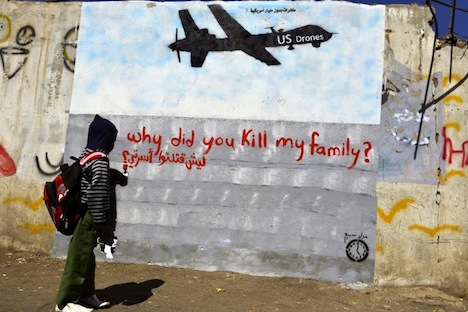

In a speech just four years ago, US admiral Mike Mullen, then chair of the joint chiefs of staff, outlined the US government’s approach to Yemen in an address to the US Naval War College. By 2010, Yemen, which lies on the southwestern edge of the Arabian peninsula, had become an increasingly worrying front in US global efforts to confront Islamic terrorism:

Mullen said people ask him often if the United States is going to send troops to the nation. “The answer is we have no plans to do that, and we shouldn’t forget this is a sovereign country,” he said. “Sovereign countries get to vote on who comes in their country and who doesn’t.”

In what is the first vote of its kind, Yemen’s parliament voted on Sunday for a halt to US-initiated drone strikes that locals say killed more than a dozen civilians in a wedding party on December 11 — the attack, which took place in the central Yemeni province of al-Baydaa, is just one of many strikes in 2013, and it’s not the first one to have resulted in civilians deaths. But the attack attracted widespread condemnation from both inside Yemen and internationally, leading to Sunday’s unanimous parliamentary vote.

In light of the ‘Mullen doctrine,’ you might expect the United States to pause its drone strikes on the country, right?

Wrong. The parliamentary vote wasn’t binding on the Yemeni government, and Yemen’s parliamentary powers pale in comparison to those of the president, Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, vice president between 1994 and 2012 and the hand-picked successor to Yemen’s longtime ruler Ali Abdullah Saleh and the Yemeni ruling party, the General People’s Congress (المؤتمر الشعبي العام, Al-Mo’tamar Ash-Sha’abiy Al-‘Aam), which itself controls 238 of the 301 seats in Yemen’s Majlis al-Nuwaab (House of Representatives).

Yemen, alongside Tunisia and Egypt, was among the vanguard of countries where the so-called Arab Spring peaked — though Saleh held on through mass protests in January and February 2011 against corruption and economic mismanagement, an assassination attempt in July 2011 left him severely injured and burned. But the stage-managed transition from Saleh to Hadi has barely addressed the long-standing complaints of the Arab Spring protestors, let alone the more fundamental regional divides that have long plagued Yemen, which emerged as two quasi-independent states in 1918 out of the collapse of the Ottoman empire.

Meanwhile, the US government denies that the December 11 drone strike killed anyone but ‘militants,’ despite evidence to the contrary and a deluge of protest across the Arab world. Even the United Nations is now calling on the United States to provide answers about the error.

As Adam Baron, a reporter based in the Yemeni capital of Sana’a wrote last week in Foreign Policy,

The exact nature of the error is still a matter of speculation. It was hard not to wonder if the wedding convoy was mistaken for something more sinister — that someone in the bowels of the U.S. intelligence community concluded that vehicles carrying heavily armed wedding guests were actually an al Qaeda convoy. Some tribal contacts said that there were high-ranking militants near the site of the strike, and a Yemeni official briefed on security matters told me a vehicle hit in the attack had been linked to a prominent local al Qaeda leader. Either way, any “suspected militants” present were surrounded by civilian bystanders.

Nonetheless, the United States seems unlikely to swerve from its low-grade war against Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). The drones will continue — and they will, in all likelihood, continue to kill innocent civilians, each of which has the potential to drive everyday Yemenis closer to AQAP and away from the United States. Just last week, when AQAP attacked Yemen’s defense ministry, it also accidentally struck people in a hospital inside the ministry — and its leaders were fast to apologize for the error in targeting the hospital and agreed to pay ‘blood money’ to the relatives of those killed in the attack.

How did we get to the point where al-Qaeda seems more accountable than the Obama administration for civilian deaths in Yemen?

Jeremy Scahill’s tour de force about the covert and clandestine operations of both the Obama administration and the administration of George W. Bush, Dirty Wars: The World is a Battlefield, calls into question the legality of much of the basis for the notion that the executive branch can claim the entire world is essentially the ‘battlefield’ for the global war on terror. In particular, the Obama administration’s record in Yemen alone remains troubling.

Abdulrazaq Al-Jamal, an expert specializing in Al-Qaeda affairs, summarized the Yemeni argument against the US strikes in an interview earlier this week with the Yemen Times, arguing that the US drone strikes are illegal, that they encourage AQAP and they expose Yemen’s own government as a failure:

I think there is no difference between the raid that targeted the wedding convoy in Ra’ada and the previous raids that targeted Al-Qaeda and any Yemeni [citizens]. American [spying] and shelling, in principle, is wrong because it kills illegally and without trial. I cannot differentiate between strikes that target Al-Qaeda members and strikes that [might] target citizens because these strikes are [made outside of the legal system]. I disagree with those who differentiate between them because it is a violation of Yemeni sovereignty to kill [any Yemeni citizens, be they Al-Qaeda members or not]….

I don’t think that American drones are [stopping tribes from] protecting Al-Qaeda members as [drones] may cause several tribes to [actually] join Al-Qaeda. I think that if American drones continue to violate Yemen’s sovereignty and kill civilians, the tribes will not only protect Al-Qaeda affiliates but will join Al-Qaeda themselves. Seeking help from American drones [instead of handling Al-Qaeda itself] proves that the Yemeni government is a failed one.

Saleh, and now Hadi, have played a wily game of rope-a-dope with the United States in the post-9/11 era, seeking ever more funding and training for forces to fight ‘terrorism,’ while routinely deploying those forces in furtherance of pushing back against internal regionalists. Most recently, that means the Shiite Houthi rebellion that began in the mid-2000s in northeastern Yemen, but it also includes forces to maintain tentative control over south Yemen, a wide swatch of country that includes not only the southern shore and the key port of Aden, but also the eastern half of Yemen that borders Oman. Saleh, who came to power in north Yemen in 1978, only managed to unify the two parts of Yemen in 1990, and even then, fought a civil war in 1994 and continual unrest thereafter. As AQAP grew in Yemen, south Yemen has become a territorial stronghold in a country where local power still runs on largely tribal lines, and the line between tribal leader and militant leader is often dazzlingly blurred. While Yemen is also split on religious lines (around 45% to 50% of the country belongs to the Zaydi Shi’a sect and around 50% to 55% of the country is Sunni) Yemen’s Shiites are clustered in the northwestern corner of the country.

US meddling comes at a delicate time for Yemen, whose leaders are working on a new agreement to grant self-rule powers to the autonomous south in a move toward a more federal Yemen. The powerful Yemeni Socialist Party (الحزب الاشتراكي اليمني, Al-Hizb Al-Ishtiraki Al-Yamani), which controlled south Yemen during its period of independence through 1990, opposes the latest effort, and it continues to support a two-region state, not the six-region state that Hadi and the current Yemen government supports. If an agreement can be reached, Yemenis will vote in a constitutional referendum in February 2014. Continue reading Will the US respect Yemeni parliament’s vote on drone attacks? →

![]()