There’s a segment of the US foreign policy community that simply doesn’t care much for the likely winner of this weekend’s Salvadoran presidential election, Salvador Sánchez Cerén — and it’s making its displeasure loud in the days leading up to Sunday’s runoff vote.

First, Elliott Abrams, former deputy national security adviser under US president George W. Bush, argued back in early January in The Washington Post that Sánchez Cerén (pictured above) represents a backslide for El Salvador, arguing further that ‘democracy and peace in Central America are again at risk’:

The likely impact of a Sánchez Cerén victory on U.S.-Salvadoran security and counter-narcotics cooperation is dangerous. The United States has a key forward operating location in El Salvador to monitor and deter drug trafficking, and the FBI cooperates with local police against trafficking by Salvadoran gangs. Could such activities continue in light of the FMLN’s ties to the FARC and to the Venezuelan government?

Yesterday, José R. Cárdenas, also a former official in the Bush administration, added his alarm in Foreign Policy, where he echoes the same kind of panic over a Sánchez Cerén victory:

What an FMLN victory means for El Salvador and the region under a Sánchez Cerén presidency is particularly worrisome. Unlike current President Mauricio Funes of the FMLN, with Sánchez Cerén there is no pretense to moderation. Beneath the democratic mask, he still adheres to the hard-line agenda of the FMLN, honed during the dirty war against the Salvadoran state in the 1980s.

Funes, as the candidate of the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN, Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front), the guerrilla group from the 1980s that transformed more than two decades ago into El Salvador’s primary center-left political party, won the presidency for the Salvadoran left for the first time in the country’s postwar history. Sánchez Cerén is more ideologically motivated than Funes, who came to politics from journalism, unlike Sánchez Cerén, who came to politics directly from the front lines of El Salvador’s 1979-92 civil war.

Sánchez Cerén’s running mate, Óscar Ortiz, is the widely popular mayor of Santa Tecla and a moderate figure within the FMLN, and many Salvadorans believe it always should have been Ortiz leading the FMLN’s 2014 ticket. His appeal is one of the reasons Sánchez Cerén seems like such a lock to win Sunday’s election (at least as much as the ‘masterful political ads that managed to convert a battle-hardened ideologue into a kindly, old grandfather’ that Cardenás attributes to the FMLN’s success). Sánchez Cerén, who has served Funes loyally as vice president for five years, and Ortiz, who will want to succeed Sánchez Cerén in 2019, both have an incentive to pursue continuity with the relatively moderate Funes government. Sánchez Cerén would not be the first Latin American firebrand to govern with a pragmatic approach in office — e.g., Peruvian president Ollanta Humala.

Following the end of the civil war, El Salvador developed a relatively stable trajectory and, until 2009, the center-right Alianza Republicana Nacionalista (ARENA, Nationalist Republican Alliance) won every consecutive presidential election. It’s true that the Funes administration has nudged Salvadoran public policy leftward, especially with respect to social welfare, and that Funes has availed his country of some of the economic benefits of closer ties with Venezuela and other US opponents in Latin America. But ultimately, his administration hasn’t abandoned the broad Salvadoran consensus toward neoliberal economic policy or the country’s decision a decade ago to abandon its national currency in favor of dollarization. Funes’s leftism has been more of the pragmatic, business-friendly lulista variety than the populist, dogmatic chavista alternative:

But as president, Funes has expanded social welfare benefits — abolishing public health care fees, combatting illiteracy, providing food and clothing to schoolchildren, granting title to disputed land claims, introducing monthly stipends and job training for the poorest Salvadorans, and signing legislation to protect women, sexual minorities and indigenous communities. He’s also oriented El Salvador closer to the Venezuela-led Alianza Bolivariana (ALBA, Bolivarian Alliance) while retaining strong ties with the United States.

By the way, the Salvadoran business community has welcomed Funes’s outreach to Venezuela and ALBA because, as Frederick Mills wrote late last year in a great primer on the Salvadoran race, the private sector is enjoying access to new markets in addition to its long-standing access to US markets.

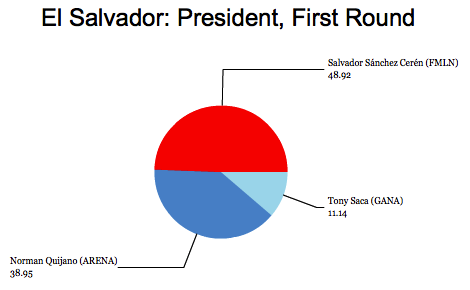

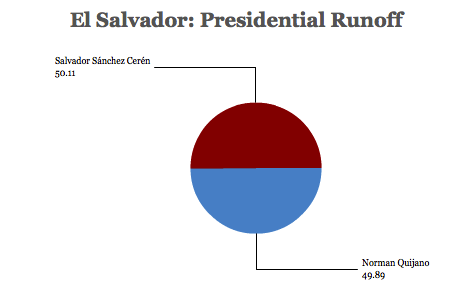

In the first round of the election on February 2, Sánchez Cerén won 48.92% of the vote, while center-right San Salvador mayor Norman Quijano won 38.95%. The third-place candidate, former president Elías Antonio ‘Tony’ Saca won just 11.44%. Saca, notwithstanding his former ties to ARENA, has so far refused to endorse either Quijano or Sánchez Cerén in the runoff — that’s a blow to Quijano, who hopes to consolidate the right-leaning vote to pull off an upset in the March 9 runoff.

But there’s some troubling revisionism in both hit pieces by Cardenás and Abrams that should leave us all skeptical about their narratives of the current election campaign. Continue reading The US whispering campaign against Sánchez Cerén →

![]()