In case you missed it over the weekend, China’s state-run newspaper Xinhua printed an extraordinary editorial calling for a turn to a ‘de-Americanized’ world that appears to have had the support of the top leadership within the world’s most populous country:

As U.S. politicians of both political parties are still shuffling back and forth between the White House and the Capitol Hill without striking a viable deal to bring normality to the body politic they brag about, it is perhaps a good time for the befuddled world to start considering building a de-Americanized world….

The tone only sharpens as the editoral blames the United States for torturing prisoners and killing civilians in drone attacks before fully condemning the era of ‘pax Americana‘:

Moreover, instead of honoring its duties as a responsible leading power, a self-serving Washington has abused its superpower status and introduced even more chaos into the world by shifting financial risks overseas…

Most recently, the cyclical stagnation in Washington for a viable bipartisan solution over a federal budget and an approval for raising debt ceiling has again left many nations’ tremendous dollar assets in jeopardy and the international community highly agonized.

Elements of the editorial are somewhat biased — a self-serving ding against Washington for ‘instigating regional tensions amid territorial disputes’ is more reminiscent of Chinese bluster and blunder on relations with Taiwan, Hong Kong and Tibet, as well as the recent territorial dispute with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. But if, as is almost certainly the case, the editorial has the backing of top Chinese leadership, it will be the strongest call to date for a move to a ‘de-Americanized’ world.

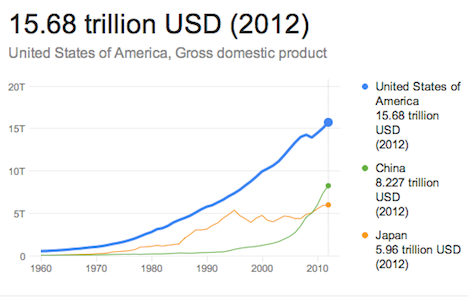

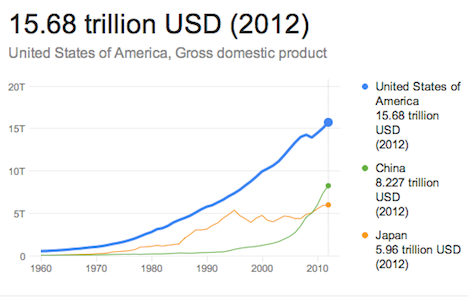

It’s important to keep in mind that, for all the defeatist talk that China has eclipsed the United States, the US economy remains roughly twice the size of the Chinese economy:

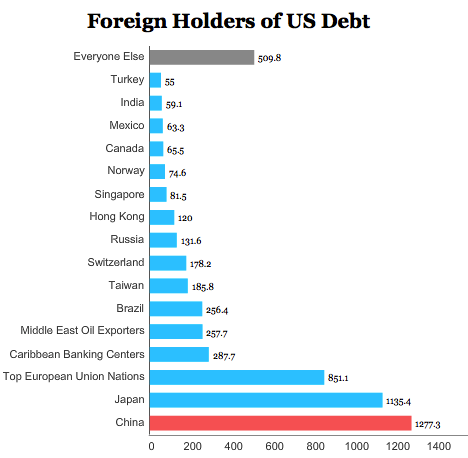

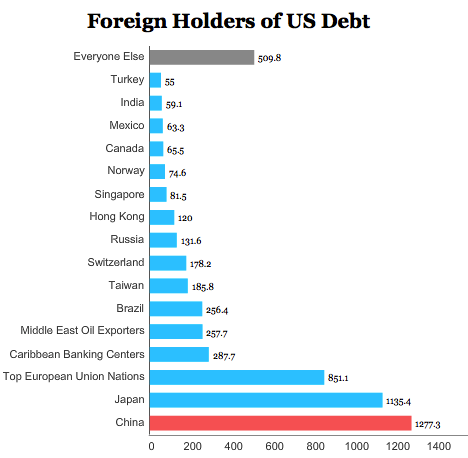

Furthermore, for all of the talk that the United States is becoming ever-more indebted to the Chinese, it’s also important to keep in mind that of the $16.7 trillion or so in outstanding US debt issuance, around $4.7 trillion amounts to intergovernmental holdings (e.g., amounts held by the US Federal Reserve). Another significant chunk of that debt is held by state and local pension funds, the Social Security Trust Fund. In fact, as of July 2013, foreign governments held just $5.59 trillion of the debt, and China held just $1.277 trillion of it, while Japan held nearly as much with $1.135 trillion. Here’s a closer look at the breakdown of the foreign holders of US debt:

In all the loose talk about China’s rise, it’s easy to lose track of those two items — China holds just over 7.6% of all US debt and its economy is just 52.5% the size of the US economy.

So while China isn’t today in a position to issue edicts about the de-Americanization of the world economy, its views are becoming increasingly influential, especially as it takes a greater investment role within the world from Latin America to Africa. Its call for developing and emerging market economies to play a greater role in international financial institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund mean that the days of an always-American World Bank president and an always-European IMF managing director are numbered.

Even in the worst-case scenario in which the US Congress’s failure to lift the debt ceiling leads to another Lehman-style panic, China can’t do much immediately to bring about a de-Americanized world. But, like Humphrey Bogart’s warning to Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca, the threat will come ‘maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon — and for the rest of your life.’

So when China makes noise about a de-Americanized world, it essentially means two things: a world where US debt is no longer perceived as the world’s safest investment and the US dollar is no longer the world’s reserve currency. I’ll take a look at each in turn, but first, it’s worth making sure we’re all on the same page as to the basics of the debt ceiling standoff itself.

The debt ceiling crisis

US treasury secretary Jack Lew has pinpointed October 17 as the day that the United States will be truly jeopardized by its failure to raise the debt ceiling (currently at $16.7 trillion).

With about 24 hours to go until the world hits that deadline, the Republican Party, which controls a majority of the votes in the US House of Representatives, are nowhere near approving a bill that, with or without conditions, would raise the debt ceiling for even a short period of time, and the US Senate, which is controlled by the Democratic Party, will spend Wednesday taking the lead on a last-ditch effort at negotiations between Senate majority leader Harry Reid and Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell.

It’s reassuring to know that Moody’s isn’t quite as pessimistic about the October 17 deadline — in a memo from earlier this month, Moody’s experts argued that the US government could quite possibly hobble along, quite possibly until November 1, when a slew of entitlement spending means that the US government will be unlikely to meet its obligations on time. The US government will certainly prioritize interest payments on US debt and meet its other obligations on the basis of incoming revenues. But the clock’s ticking, and while Wall Street and global markets seem nonplussed about the shutdown and even about the October 17 debt ceiling deadline, there’s no way to know when that could change.

Market sentiment is a tricky thing to forecast — recall the speed in 2008 with which former US treasury secretary Hank Paulson went from worrying about the moral hazard of bailing out Lehman Brothers on September 14 to, less than 24 hours later, worrying about rescuing the entire financial system from a global panic. While it seems unlikely that markets will immediately tank at midnight tonight if the US Congress fails to act on the debt ceiling, there are signs that other actors in the global economy are running out of patience. One of the other top three credit ratings agencies, Fitch, put the United States on warning Tuesday by lowering the outlook on its ‘AAA’ credit rating from ‘stable’ to ‘negative,’ citing the brinksmanship in the US political system that’s so far failed to secure a debt ceiling hike.

For those of you who might have been living on a deserted island for the past three years, the US Congress is generally obligated to raise the total aggregate amount of US debt issued, irrespective of whether the US Congress has approved the spending levels associated with issuing such additional debt. No other country (except Denmark) has a similar concept, which is why the debt ceiling crisis is such a foreign concept for non-Americans.

Between 1798 and 1917, the US Congress had to approve every single issuance of new debt; the onset of the ‘debt ceiling’ concept was initially a way to streamline debt issuance during World War I. Since 1917, the US Congress raised the debt ceiling over 100 times, and 14 between 2001 and 2013. Traditionally, in times of divided US government, though those votes have sometimes been subject to one party’s political posturing. US president Barack Obama himself cast a vote against raising the debt ceiling in 2006 when he was just a US senator, and he issued some pious, if garden-variety, blather about ‘shifting the burden of bad choices today onto the backs of our children and grandchildren.’ Matt Yglesias at Slate called out Obama for ‘bullshitting’ back in 2006.

But only in 2011 did one party seek to wield the debt ceiling as a weapon of economic destruction — give us what we want on our policy priorities or the world economy gets it! In 2011, just months after Obama’s party suffered devastating losses in the November 2010 midterm elections, Obama agreed to make budget cuts in exchange for a hike in the debt ceiling. But now, fresh off reelection, Obama is arguing that he won’t negotiate over the debt ceiling — partly to discourage anyone from trying to use the debt ceiling as an instrument of political blackmail in the future.

In any event, for the best reporting in the United States on the debt ceiling crisis in terms of both politics and policy, go read Ezra Klein (and friends) at Wonkblog at The Washington Post and every word that Robert Costa at National Review reports from within the House and Senate Republican caucuses.

But it’s vitally important to the global economy because US debt — Treasury debt securities (called ‘Treasurys’) and, specifically 10-year Treasurys (called ‘T-notes’) — is generally viewed as the safest investment in the world.

Why US Treasurys are so special

As Felix Salmon at Reuters memorably explained Tuesday, US-issued debt is the ‘risk-free vaseline which greases the entire financial system’: Continue reading Amid debt ceiling showdown, China sharply calls for a ‘de-Americanized’ world →

![]()