There’s a neighborhood in Los Angeles, commonly known as Tehrangeles, that is home to up to a half-million Persian Americans, most of whom fled Iran after the 1979 Islamic republic or who are their second-generation children and third-generation grandchildren, all of them American citizens. ![]()

The neighborhood runs along Westwood Boulevard, and it is home to some of the wealthiest Angelinos. But under the executive action that US president Donald Trump signed Friday afternoon, their relatives in Iran will have a much more difficult time visiting them in Los Angeles (or elsewhere in the United States). The impact of the order, over the weekend, proved far deeper than originally imagined last week when drafts of the order circulated widely in the media.

The ban attempts to accomplish at least five different actions, all of which began to take effect immediately on Friday:

- First, the order institutes a ban for 90 days on immigrants from seven countries — Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Somalia and Libya.

- Secondly, the ban initially seemed to include even US permanent residents with valid green cards with citizenship from those seven countries (though the Department of Homeland Security was walking that back on Sunday, after reports that presidential adviser and former Breitbart editor Steve Bannon initially overruled DHS objections Friday). But it also includes citizens of third countries with dual citizenship (which presents its own problems and which the White House does not seem to be walking back).

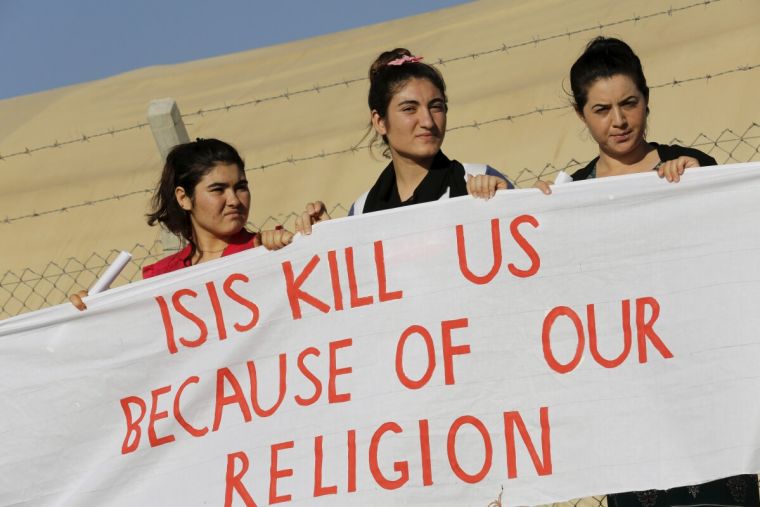

- Third, it institutes a 120-day freeze on all refugees into the United States from anywhere across the globe and an indefinite ban for all refugees from Syria.

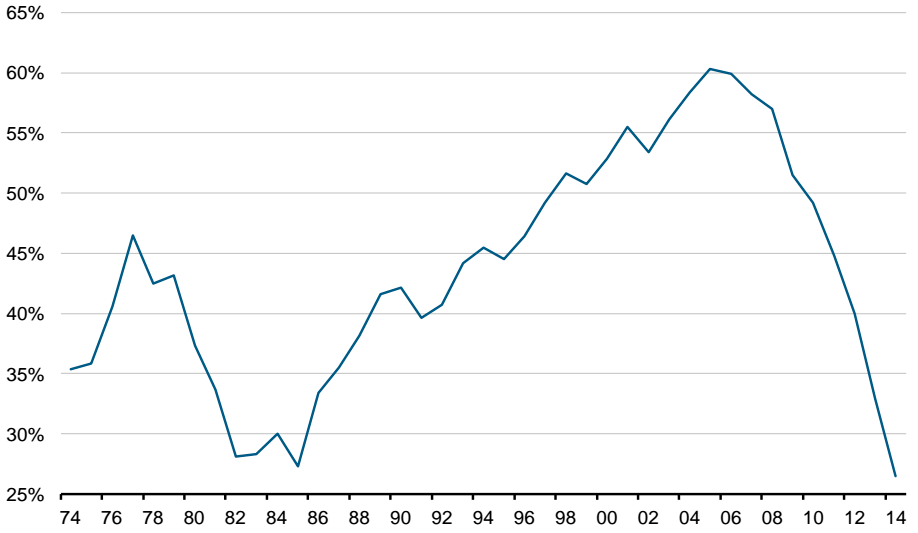

- Fourth, it places a cap of 50,000 on all refugees for 2017 — that’s far less than nearly 85,000 refugees who were admitted to the United States in 2016, though it’s not markedly less than the nearly 55,000 refugees admitted in 2011 (the lowest point of the Obama administration) and it’s more than the roughly 25,000 to 30,000 refugees admitted in 2002 and 2003 during the Bush administration.

- Fifth, and finally, when the United States once again permits refugees, it purports to prioritize admitting those refugees ‘when the person is a religious minority in his country of nationality facing religious persecution.’ It’s widely assumed that this is a back-door approach to prioritizing Christian refugees. More on that below.

In practice, it’s already incredibly difficult to get a visa of any variety if you are coming from one of those countries, with a few exceptions. But formalizing the list is both overbroad (it captures mostly innocent travelers and refugees) and underbroad (it doesn’t include potential terrorists from other countries), and experts believe it will hurt US citizens, US businesses and bona fide refugees who otherwise might have expected asylum in the United States. On Sunday, many Republican leaders, including Arizona senator John McCain admitted as such:

Ultimately, we fear this executive order will become a self-inflicted wound in the fight against terrorism. At this very moment, American troops are fighting side-by-side with our Iraqi partners to defeat ISIL. But this executive order bans Iraqi pilots from coming to military bases in Arizona to fight our common enemies. Our most important allies in the fight against ISIL are the vast majority of Muslims who reject its apocalyptic ideology of hatred. This executive order sends a signal, intended or not, that America does not want Muslims coming into our country. That is why we fear this executive order may do more to help terrorist recruitment than improve our security.

On the campaign trail, Trump initially called for a ban on all Muslims from entering the country; when experts responded that such a broad-based religious test would be unconstitutional, Trump said he would instead extend the ban on the basis of nationality.

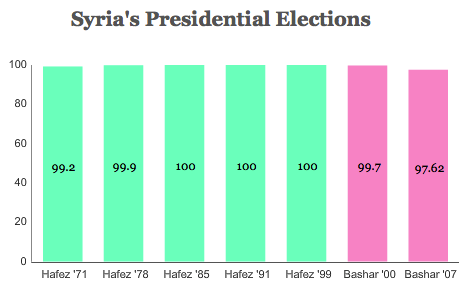

Friday’s executive action looks like the first step of institutionalizing the de facto Muslim ban that Trump originally promised (thought it would on its face be blatantly unconstitutional).

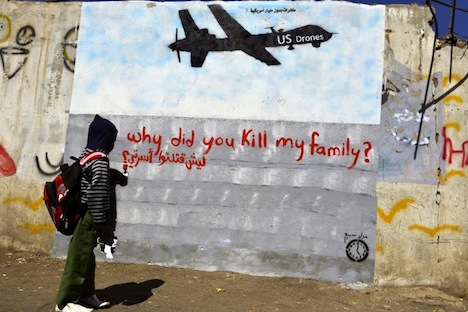

Of course, as many commentators have noted, the list doesn’t contain the countries that match the nationalities of the September 2001 hijackers — mostly Saudi Arabia. But it doesn’t contain Lebanon, though Hezbollah fighters have aligned with Syrian president Bashar al-Assad in that country’s civil war. It doesn’t include Egypt, which is the most populous Muslim country in north Africa and home to one of the Sept. 2001 terrorists. Nor does it include Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country. Nor Pakistan nor Afghanistan, where US troops fought to eradicate forms of hardline Taliban government and where US troops ultimately tracked and killed Osama bin Laden.

This isn’t a call to add more countries to the list, of course, which would be even more self-defeating as US policy. But it wouldn’t surprise me if Bannon and Trump, anticipating this criticism, will use it to justify a second round of countries.

In the meanwhile, the diplomatic fallout is only just beginning (and certainly will intensify — Monday is the first full business day after we’ve read the actual text of Friday’s executive order). Already, Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel, citing the obligations of international law under the Geneva Conventions, disavowed the ban. Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau used it as an opportunity to showcase his country’s openness to immigration and welcomed the refugees to Canada. Even Theresa May, the British prime minister who shared a stage with Trump in Washington on Friday afternoon, distanced herself from the ban, and British foreign minister Boris Johnson called it ‘divisive.’

But the most direct impact will be felt in relations with the seven countries directly affected by the ban, and there are already indications that the United States will suffer a strategic, diplomatic and possible economic price for Trump’s hasty unilateral executive order. Continue reading A country-by-country look at Trump’s immigration executive order