The problem with South Africa’s opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), has always been that it is viewed as a party for wealthy whites — even when its former leader, Helen Zille, was a longtime anti-apartheid journalist. ![]()

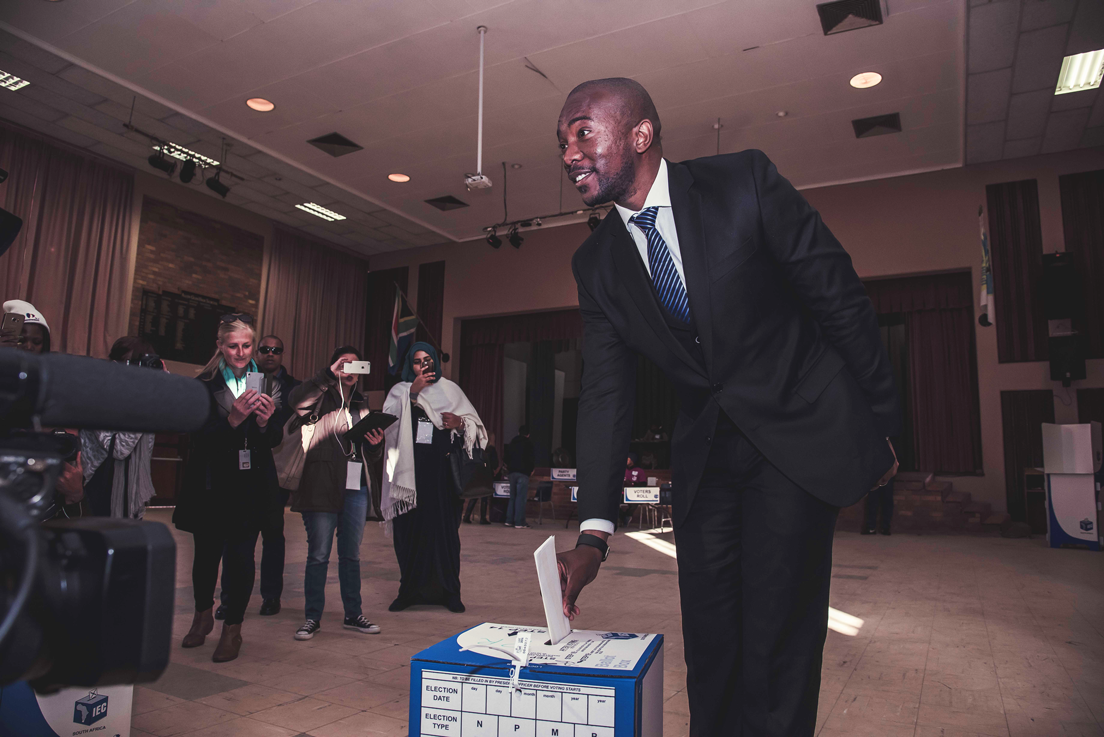

The rap on the DA’s new leader, Mmusi Maimane, is that the 36-year-old was far too inexperienced to navigate the South Africa’s complicated racial politics, long dominated in the post-apartheid era by the African National Congress (ANC). Even under Maimane’s leadership, ANC leaders and others routinely slam the Democratic Alliance, somewhat unfairly, for a ‘legacy of racism.’

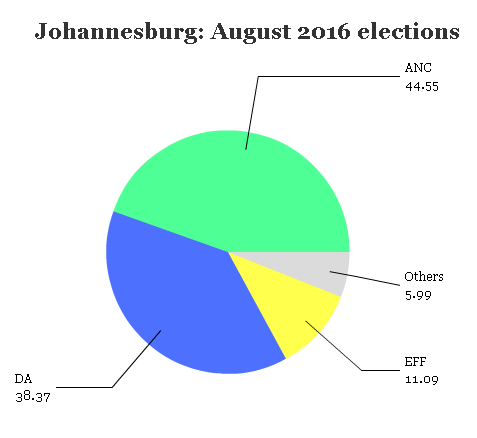

But the DA’s success in last week’s municipal elections may force South Africans to reconsider their views both about the party and its young leader. Voters across the country recoiled at the economic malaise, corruption and other shenanigans that have accumulated under Jacob Zuma, the country’s president since 2009, handing several victories to the DA, which fell just shy of winning in Johannesburg, South Africa’s most populous city.

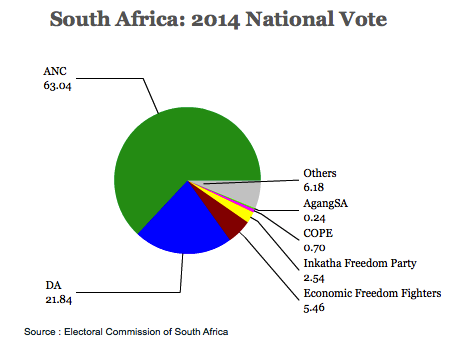

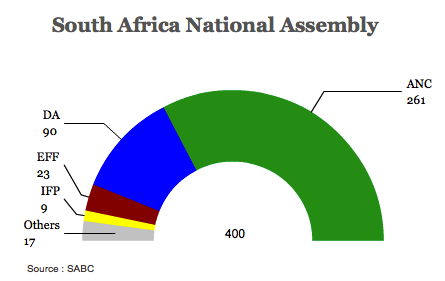

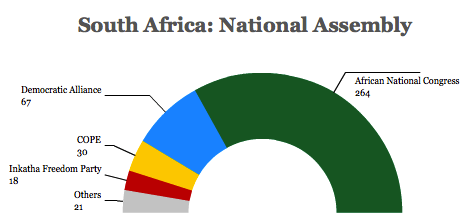

In the May 2014 general election, the Democratic Alliance had its best showing to date, even though it meant winning just 22.23% of the vote nationwide, compared to 62.15% for the ruling ANC. Historically, the DA has managed to attract a wide majority in Western Cape province and in the city of Cape Town, but it has struggled elsewhere in an uphill battle to convince voters to abandon the ANC, the party of Nelson Mandela that’s still synonymous with the end of apartheid.

More than two decades after the ANC came to power, however, unemployment is on the rise, GDP growth has slowed, and Zuma faced a rebuke earlier this spring from South Africa’s top constitutional court, which ordered him to repay some of the $23 million in public funds that Zuma spent to renovate his Nkandla home. One of the much-hyped BRICS economies, South Africa hasn’t achieved GDP growth over 4% since 2007, and growth slowed increasingly in the past three years — the economy is expected to grow by just 0.1% this year.

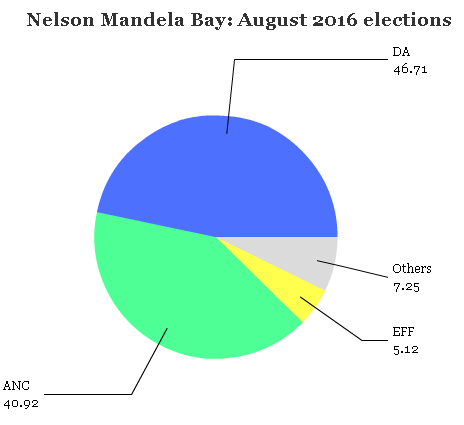

Election officials confirmed late last week that the Democratic Alliance won in Nelson Mandela Bay, a municipality that includes Port Elizabeth, the largest city of Eastern Cape province.

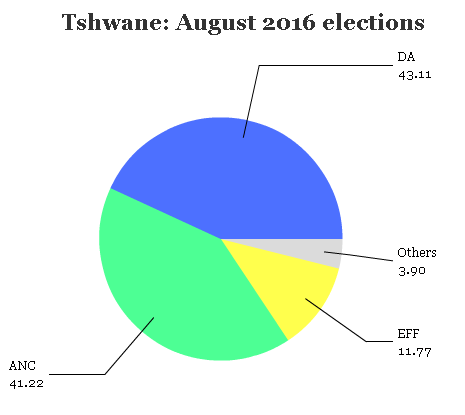

Over the weekend came even more stunning news that the Democratic Alliance narrowly edged out the ANC in Tshwane municipality (which includes Pretoria, South Africa’s administrative and executive capital) and only narrowly lost Johannesburg. Both cities are in Gauteng province, which has been a Maimane target for a while, dating back to his own mayoral run in Johannesburg in 2011.

Voters across the country voted on August 3 for municipal councils at several levels of government. The largest prizes include the councils of eight metropolitan municipalities, which include South Africa’s most populous cities.

Voters across the country voted on August 3 for municipal councils at several levels of government. The largest prizes include the councils of eight metropolitan municipalities, which include South Africa’s most populous cities.

In addition to Nelson Mandela Bay, Tshwane and Johannesburg, those eight municipalities also include the DA-controlled Cape Town and four additional councils that the ANC easily retained (including, for example, the eThekwini municipality that includes Durban).

The results mean that the DA (in Pretoria and Port Elizabeth) and the ANC (in Johannesburg) will both scramble either to align with the leftist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) or to try to govern with a minority.

The results mean that the DA (in Pretoria and Port Elizabeth) and the ANC (in Johannesburg) will both scramble either to align with the leftist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) or to try to govern with a minority.

Continue reading DA impresses with wins in South African municipal elections