It’s a slow election year in Germany, so there will be few tests at the state level for chancellor Angela Merkel, her center-left ‘grand coalition’ partners or any of the various challengers to Merkel’s hold on German centrism.![]()

![]()

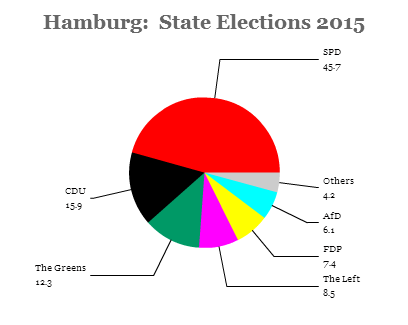

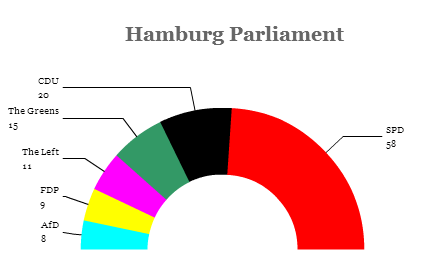

That makes the results from Sunday’s election in Hamburg, a city-state in the German north, perhaps more important than they otherwise would be, and it’s not great news for Merkel’s center-right Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Union), which won just one-third as much support as its center-left rival (and partner in federal government), the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party).

* * * * *

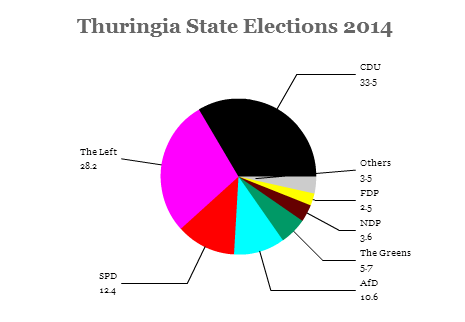

RELATED: Thuringia and Brandenburg election results —

Left, AfD on the rise

* * * * *

The CDU and the SPD continue to be the largest of Germany’s political parties and, notwithstanding the fact that they have joined together in the second ‘grand coalition’ in 10 years, the two parties fight fiercely at the state level and will contest Germany’s next national elections later this decade. Nevertheless, it wasn’t unexpected that the SPD, under the leadership of Hamburg first mayor Olaf Scholz (pictured above), would easily win the election. Though the SPD lost four seats, enough to deprive it of its absolute majority, Scholz will almost certainly form the next government, likely with Die Grünen (the Greens).

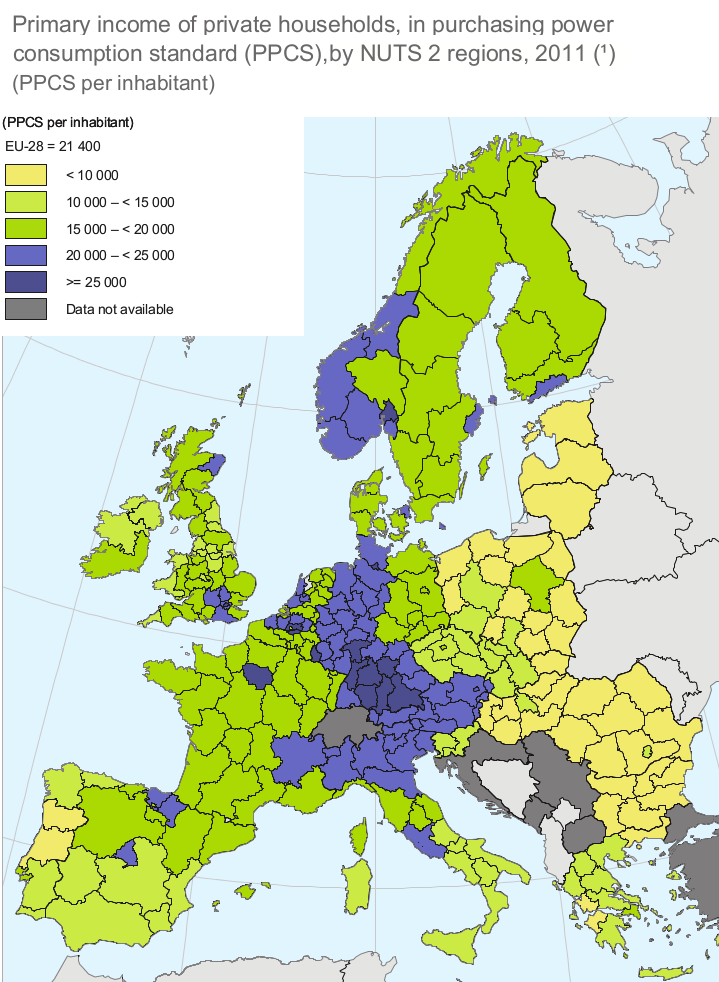

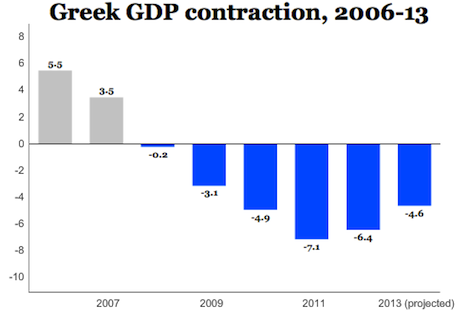

The troubling aspect for the CDU isn’t that it did so poorly in Hamburg, which has traditionally leaned toward the SPD, but that it seems to be losing voters to more right-wing alternatives, including the mildly eurosceptic Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany), which actively advocates that Greece and other countries leave the eurozone. It’s the four state where the AfD has now surpassed the minimal threshold to win seats in the state parliament/assembly. Continue reading AfD, FDP thrive in Hamburg state elections