Though Sunday’s unofficial referendum on Catalan sovereignty may have been legally murky, it is nonetheless clear that Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy’s strategy of ignoring the groundswell of support for regional self-determination and autonomy has been a failure.

So what actually happened on Sunday — and where do the Catalan nationalist movement and the Spanish government go from here?

What happened in Sunday’s ‘consultation’ vote

Photo credit to AFP.

Photo credit to AFP.

Catalans voted in a non-binding, unofficial ‘consultation’ that its Generalitat (or regional government) once hoped would be a legal referendum not unlike the recent September vote on independence in Scotland. But Rajoy has refused to countenance even the idea of negotiating the terms of such a referendum, and he has consistently ruled out any vote as unconstitutional.

Nevertheless, Catalunya’s regional president Artur Mas (pictured above) has championed a referendum since at least 2012, and his party and other more radical groups in the Catalan regional parliament overwhelmingly voted to hold the referendum, setting the central and Catalan regional governments on what has been a divisive battle over the past year.

* * * * *

RELATED: Mas cancels official Catalan independence vote

* * * * *

Mas backed down on the ‘official’ nature of the referendum, which in any event was always designed to be non-binding, when Spain’s constitutional court ruled that the vote was illegal last month. Much to the chagrin of other, more leftist nationalists, however, Mas instead moved forward with an unofficial referendum, taking care not to use official Spanish government resources to conduct the vote.

The Spanish constitutional court ruled last week, in a second decision, that even this unofficial, non-binding ‘consultation’ should be delayed until it could have time to rule on its further legality. Mas went ahead with the vote, anyway, however, prompting a sharp rebuke from Rajoy’s government on Sunday:

Justice Minister Rafael Catalá described the November 9 vote as an “act of political propaganda with no democratic validity; a sterile and useless act.”

The minister went on to announce that the public prosecutor would evaluate the facts of Sunday’s vote and decide whether or not to begin legal action in the courts.

Though the law is squarely on the side of the Spanish government, the Catalans seem to have valid political and moral reasons for demanding at least a voice over their own future. In any event, at least 2.3 million Catalans turned out for the vote, representing around 35% of the total Catalan electorate, nearly all of them were pro-independence voters.

The vote asked two questions: first, ‘do you want Catalunya to be a state?’ and second, ‘if so, do you want Catalunya to be an independent state?’

The so-called ‘yes-yes’ vote won with around 80.8% of the vote. The so-called ‘yes-no’ vote (i.e., those supporters of a Catalan state, but not necessarily an independent state) won another 10.1%. ‘No’ won just 4.5% of the vote.

While that’s skewed in favor of the independence movement, it’s also not insignificant — and it indicates that a large portion of the Catalan people want a legal and valid vote on their status. The longer that Madrid assumes an ostrich position over what’s become a very real sense of grievance among everyday Catalans, the worse the standoff over independence will end. By refusing to discuss the possibility, Rajoy and the central government risk pushing moderate unionists into the arms of the Catalan nationalists.

Nevertheless, Sunday’s turnout fell far short of the 3.7 million voters who participated in the most recent November 2012 regional elections, indicating that a substantial number of voters (who presumably aren’t as enthusiastic about independence) didn’t bother to turn out. The two-pronged ballot question demonstrates the kind of too-cute-by-half ambiguity that British prime minister David Cameron refused to entertain when negotiating the Scottish referendum — what, after all, does it mean for Catalunya to be a state if not independent?

A frustrated electorate trapped between Rajoy and Mas

The most obvious solution to the standoff is a calm, rational conversation between the Mas and Rajoy governments that would result in greater autonomy for Catalunya’s Generalitat with respect to its own finances and spending. Incredibly, however, the two leaders went months earlier this year without even talking.

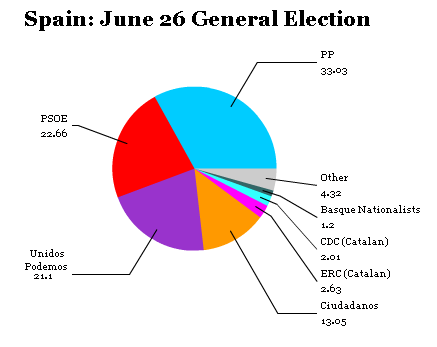

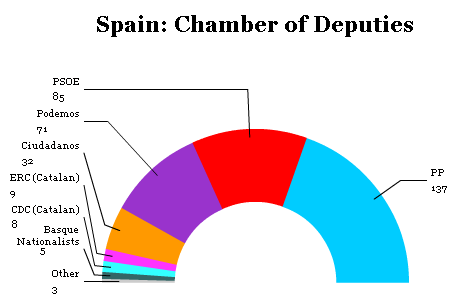

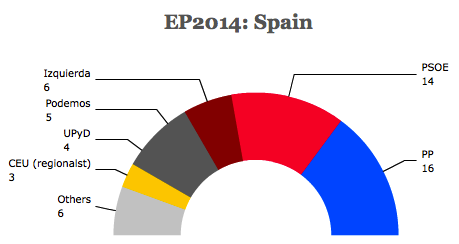

Rajoy, whose center-right Partido Popular (PP, People’s Party) won the November 2011 Spanish general elections, has consistently refused to discuss greater autonomy for Catalunya. In part, this is because Rajoy’s party has fairly little support within Catalunya — the Partit Popular de Catalunya (PPC, People’s Party of Catalonia) is just the fourth-largest bloc in the regional parliament. So Rajoy feels little immediate political pain from snubbing the region.

When he took office, Rajoy faced the likelihood that Spain would be essentially forced into a European bailout. As it turned out, Rajoy was forced into implementing budget cuts and tax increases to stave off a bailout — in addition to similar austerity measures introduced by his predecessor, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the center-left prime minister whose Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) came to power in 2004 at the dawn of the Spanish construction and finance boom.

Accordingly, Rajoy has a decent argument for avoiding a full-fledged independence referendum: with a 23.7% unemployment rate as of September, Spain is still in the midst of the worst financial and economic crisis in decades. An independence referendum in Catalunya might credibly be followed by a referendum in the Basque Country/Euskadi, another economic powerhouse with an even more painful history of separatism. Copycat movements could thrive in Galicia and elsewhere. So Rajoy has a reasonably sympathetic argument that a Catalan referendum in the midst of the current crisis could eventually pose an existential threat to the Spanish nation.

But that’s not an excuse for ignoring the problem. What’s worse is that the Spanish economic crisis is itself also fueling greater discontent among Catalans, who believe they send far more in revenue to the Spanish central government than they receive back in services and infrastructure. Though the data isn’t entirely clear, the Catalans are essentially correct. It rankles that all high-speed trains in Spain run through Madrid, for example, and that almost all of the country’s international flights arrive at the Madrid airport. Catalunya, with just 7.5 million of Spain’s 47 million citizens, is responsible for 19% of the economy.

* * * * *

RELATED: In refusing Catalan vote,

Rajoy risks isolating himself and Spain’s future

* * * * *

The Scottish referendum was also about economics (nationalists believe they can thrive as a smaller, oil-rich country within the European Union) and about politics (like the PP in Catalunya, the Conservatives have relatively little support in Scotland). But the Catalan movement is also colored by additional layers of complexity that Rajoy shows virtually no sign of appreciating — notably decades of suppression of its language and culture by the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. When Rajoy’s education minister, a few years ago, suggested a stronger national program in the Castilian language, it particularly rankled Catalans, many of whom remember the days when the Catalan language was legally banned.

But Mas, the leader of the Convergència i Unió (CiU, Convergence and Union), a two-party, center-right nationalist coalition that’s traditionally been the most powerful force in Catalan politics since the return of democracy, is hardly an honest broker. CiU has always been more comfortable with greater autonomy than full independence, and Mas only recently converted to the cause in 2012 following widespread protests. Since taking power in 2010, Mas has made many of the same painful, unpopular budget decisions at the regional level that Rajoy has made at the national level. What’s more, Jordi Pujol, the former CiU leader and Catalan president between 1980 and 2003, has been subject of increasing scrutiny over his personal wealth and corruption accusations.

Accordingly, neither Mas nor Rajoy come out of the current showdown from a incredible position of strength. That might not necessarily matter if they could at least find a middle ground to discuss the most sensible solution to the political crisis — constitutional reform, greater regional autonomy and the possible creation of a federalist system in Spain.

As elections loom, what comes next?

So far, however, the chances of any productive talks between Madrid and Barcelona seem small.

Mas has given Rajoy a two-week deadline to begin negotiations for a formal referendum. Rajoy, however, is almost certainly unlikely to take Mas up on that offer.

What happens thereafter is murky, though.

Mas’s party, the larger, more moderate and more aggressive Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC, Democratic Covergence) within the CiU, would like to hold early regional elections, rolling the dice that they would become a de facto referendum on Catalan independence — or at least the right of the Catalan government to call a vote. The smaller, Christian democratic Unió Democràtica de Catalunya (UDC, Democratic Union) has always been less enthusiastic about Mas’s push for independence and would prefer to wait on snap elections.

Part of the political calculus for Mas, Rajoy and the CiU are polls that show that the most popular party in Catalunya is now the leftist Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC, Republican Left of Catalonia), an even more radical pro-independence party led by historian Oriol Junqueras.

On paper, at least, the PP and the CiU have much more in common than the PP and Esquerra, so both Rajoy and Mas have an incentive to reach some kind of face-saving deal in the next few days.

But at the rate Rajoy is going, he may not have the opportunity to negotiate anything in the long run.

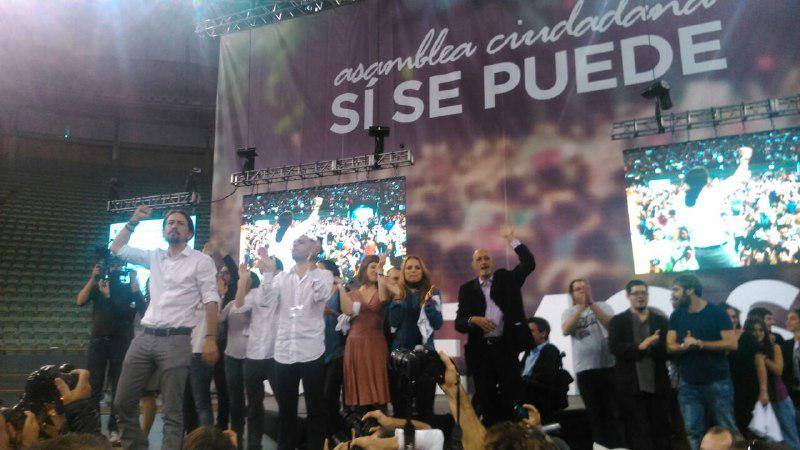

The rise of the anti-establishment Podemos (‘We can!’), the movement founded earlier this year by professor Pablo Iglesias (pictured above), has scrambled all pretenses of Spain’s two-party system. Winning five of the country’s seats to the European Parliament in May, Podemos wants to reevaluate Spain’s public debt, lower the retirement age to 60 to free up more jobs for younger workers and reverse the austerity of the past two PSOE and PP governments, using government spending to create jobs for a country that still has the highest unemployment within the European Union, despite signs of new growth. A Podemos win would be a significant setback to the orthodox policies that German chancellor Angela Merkel has attempted to establish throughout the eurozone, including the 2011 ‘fiscal compact’ that firmly limits national budget deficits to less than 3% of GDP.

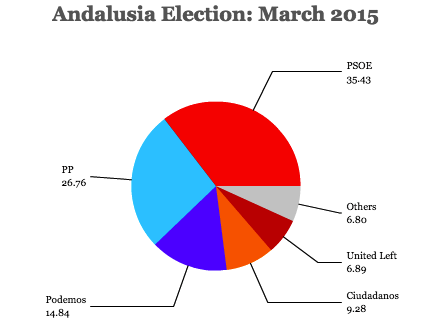

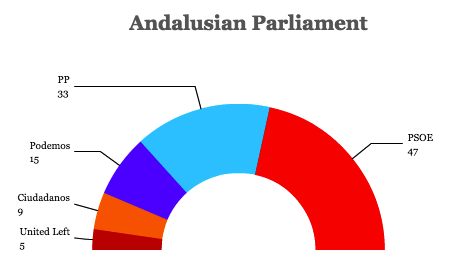

Podemos, in a shock Metroscopia poll a couple weeks ago, gained the lead among potential voters in advance of the next Spanish general election, which must be held before December 2015 — it would win 27.7% to just 26.2% for the PSOE, under the leadership of Pedro Sánchez, who won his party’s July leadership contest, and 20.7 for Rajoy’s PP. Sánchez, for his part, opposes Catalan independence, but has indicated much greater willingness to hold discussions with regional leaders over constitutional reform.

The local Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya (PSC-PSOE, Socialists’ Party of Catalonia) controlled the regional government between 2003 and 2010, and many of its members are sympathetic to the idea that Catalans should have the right to self-determination.

Though Podemos is widely viewed as a leftist alternative, it has attracted widespread support from many Spaniards who have lost faith in both major parties, especially among young voters who face the worst job prospects, and the indignados, the unemployed protestors who have given voice to the harsh effects of what are now a half-decade of austerity policies.

Ironically, Podemos has attracted little support within Catalunya, where voters have a nationalist (and leftist) alternative in Esquerra.

But as Spain nears the one-year mark until its elections, with the November 9 referendum now in the rear-view mirror, the brinksmanship between Rajoy and Mas won’t matter if they can’t find a path toward reconciliation. At this time next year, their respective governments could be headed by much more radical figures.

![]()

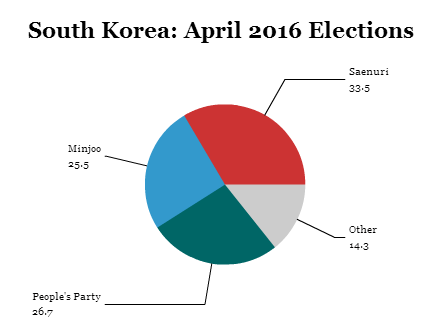

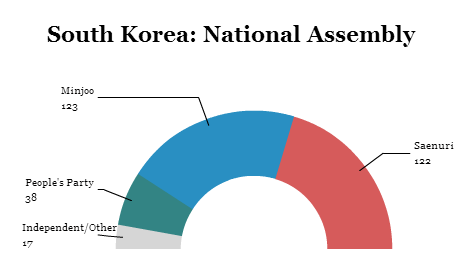

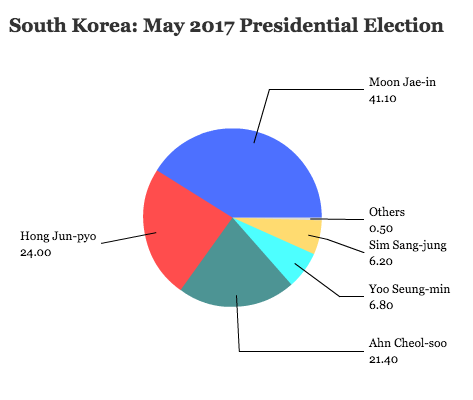

The election marks the end of nearly a decade of conservative rule in the Blue House, South Korea’s presidential office, and Moon has promised to bring a sweep of transparency and reform to domestic policy and a more conciliatory approach to North Korea in foreign policy.

The election marks the end of nearly a decade of conservative rule in the Blue House, South Korea’s presidential office, and Moon has promised to bring a sweep of transparency and reform to domestic policy and a more conciliatory approach to North Korea in foreign policy.