Bodo Ramelow (pictured above) isn’t a Stasi throwback intent on socializing Thuringia into a communist hellhole.![]()

Instead, he’s a rather boring Lutheran born in West Germany, but he could also become the minister-president of the former East German state after state elections on September 14, which could give Die Linke (Left Party) control of its only state in Germany. Thuringia is just one of three eastern states voting throughout the next month, joining Brandenburg on September 14 and Saxony two weeks earlier on August 31.

The Left Party, in particular, has a strong following in the former East Germany, given its roots as the former Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus (Party of Democratic Socialism), the successor to the Socialist Unity Party that ruled the eastern German Democratic Republic during the Cold War. As such, the traditional Western parties have been wary of partnering with the Left Party.

That’s beginning to change as the German left increasingly considers a more unified approach, and eastern Germany has been a laboratory for so-called ‘red-red coalitions’ between the Left and the center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party). As such, the Left Party served as the junior partner in Berlin’s government for a decade between 2001 and 2011 and in the state government of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern between 1998 and 2006. Furthermore, a red-red coalition currently governs Brandenburg, and its leaders hope to renew a second term for the government in September’s election.

Though the outcomes aren’t roughly in doubt, the elections take place under the backdrop of news that the eurozone could be sinking back into economic contraction. Initial numbers from the second quarter of the year showed the economy contracting by 0.2% — the first contraction since 2012 — after first-quarter growth was revised down from 0.8% to 0.7%.

* * * * *

RELATED: Has the first Ossi chancellor been

good or bad for the former East Germany?

* * * * *

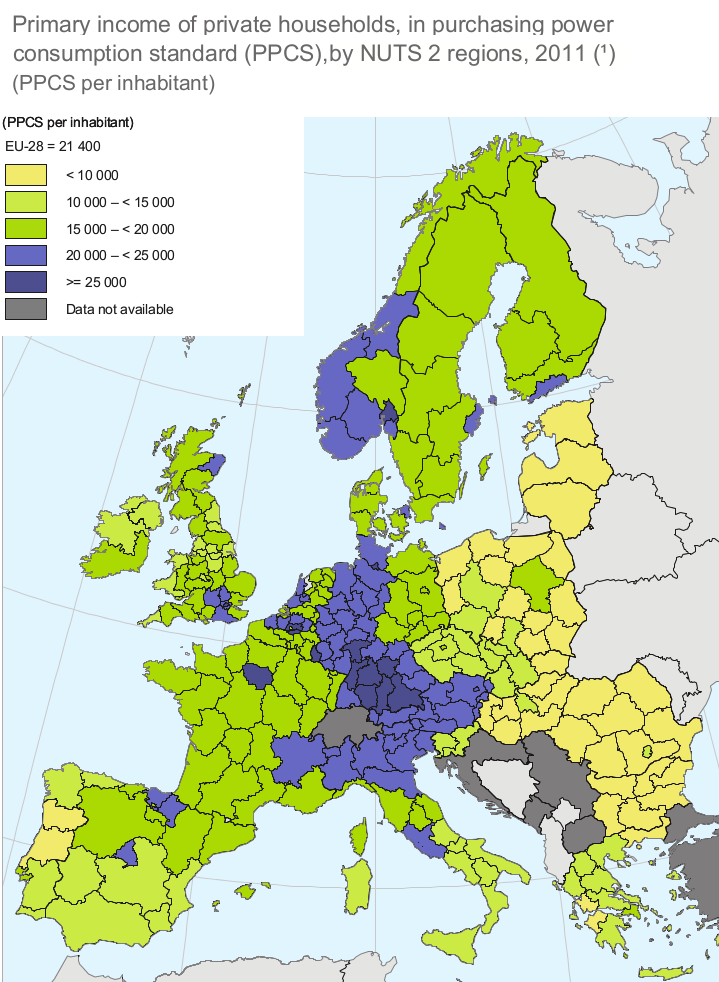

That’s in addition to the income gap that still plagues eastern Germany, where economic growth lags significantly behind the states of former West Germany, nearly a quarter-century after reunification:

The east’s lagging economic growth, the strength of Die Linke, and growing unity between the SPD and Die Linke are common themes in all three state elections over the next month.

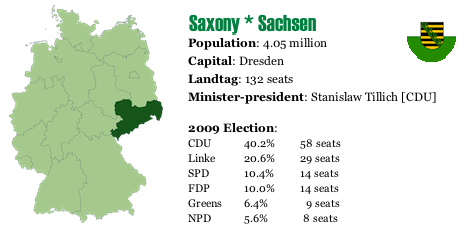

Saxony: August 31

Saxony is the most populous of the three eastern states voting over the next month, making it the biggest prize. But it’s also where the governing Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Union) of chancellor Angela Merkel are most assured of winning reelection.

Since 1990, when Saxony became a state in the newly reunited Germany, the CDU has governed the state, either in coalition with the center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) or, currently, with the liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party).

That is largely due to the forceful personality of Saxony’s first ministerpräsident, Kurt Biedenkopf, who governed from 1990 to 2002 with something of an iron fist. His long-time finance minister, Georg Milbradt, succeeded him as minister-president, much to Biedenkopf’s anger, who sacked Milbradt in 2001 over succession issues.

Bottom line: Though the largely Catholic CDU isn’t the best fit for historically Protestant Saxony, an eastern state with some of the lowest

Milbradt, who lacked Biedenkopf’s popular touch, lost the CDU’s majority in 2004, forcing the CDU to govern in a ‘grand coalition’ with the SPD. When Milbradt stepped down in 2008, the current minister-president, Stanislaw Tillich (pictured above), took office, and he led the CDU to a slightly improved result in the most recent elections in September 2009, after which the Tillich formed a government with the more economically conservative FDP.

That’s unlikely to happen again, though, as most polls show that the FDP won’t meet the 5% threshold it needs to win seats in the unicameral Landtag (state assembly). The FDP failed similarly in national elections last September, forcing it out of the German federal Bundestag for the first time since 1945. Incredibly, if the FDP doesn’t make it back into government in Saxony, it will no longer be a junior partner in any German state governments — that’s quite a collapse for a party that, until last September, controlled Germany’s foreign ministry and other key federal posts.

A recent FGW poll from late August shows the CDU with 39% support, the opposition Left with 20%, and the SPD with 15%.

In fourth place is the newly formed eurosceptic party, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany) with 7%, which narrowly missed the threshold for winning seats in last September’s federal elections. Die Grünen (the Greens) would win 6%, narrowly returning to the Landtag.

The neo-Nazi Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD, National Democratic Party) is winning around 5% support, far lower than the 9.2% it won a decade ago, and it now faces losing all of its representation in the Landtag. The FDP wins just 3%, with many of its voters decamping to the rising AfD.

Though most Saxons believe that Tillich will return to a grand coalition with the SPD, just as Merkel governs with the SPD at the federal level, he hasn’t ruled out negotiations with the Greens or, controversially, the AfD, which would mark a turning point by bringing an explicitly eurosceptic party into government for the first time in Germany. It’s not necessarily as radical as it sounds, given the heavily eurosceptic tone that many Bavarian conservatives have adopted throughout the most recent eurozone crisis. But it’s an issue that’s increasingly dominated the election and CDU strategy in the closing days of the campaign.

Bottom line: Tillich is an overwhelming favorite for reelection as Saxony’s minster-president, affirming the CDU’s anchor in the east. The FDP will likely lose representation in the Landtag, and Tillich will be forced to consider various coalitions with the center-left SPD, the Greens or the eurosceptic AfD.

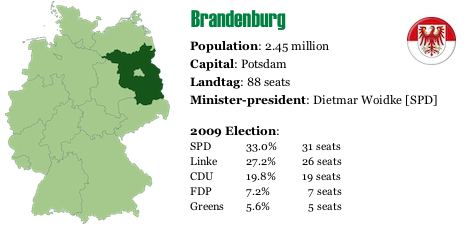

Brandenburg: September 14

As noted above, Brandenburg, which rings Berlin in northeastern Germany, is the only state currently governed by a red-red coalition between the SPD and the Left.

The SPD has governed Brandenburg exclusively since reunification, first under Manfred Stolpe from 1990 to 2002, when he left to serve as minister of transport, building and housing in Gerhard Schröder’s second term. His successor, Matthias Platzeck, a widely popular former environmental activist and environmental minister, served from 2002 to 2013, when he announced he would retire due to ill health after suffering a stroke last year.

His interior minister, Dietmar Woidke, succeeded him as minister-president last August, and Woidke (pictured above) is leading the SPD into the September 14 state elections, and he’s made it clear that he sees no reason to abandon his junior coalition partners.

An early August INSA poll gives the SPD 34%, the CDU 25%, the Left 22%, the Greens and AfD 5% each and the FDP 3%. While the FDP will almost certainly lose its seats in the Landtag, it’s possible that the AfD won’t be able to overcome the hurdle, either, and it’s even possible that the Greens could be shut out, though other polls have shown the Greens winning 6% support.

Though the AfD will struggle most to win seats in Brandenburg, the race has become the focus of a divide between the AfD’s top national leaders, who have supported greater sanctions against Russia in retribution for its aggression in Ukraine, and the top AfD candidate in Brandenburg, Alexander Gauland, whose views are more sympathetic to Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Bottom line: Like Tillich in Saxony, Dietmar Woidke is an overwhelming favorite to win reelection as minister-president in Brandenburg, which is equally an eastern anchor for the SPD. But even if the CDU narrowly overtakes the Left as the second-largest party in the Landtag, the Left seems likely to win enough support to win a second term in coalition with the SPD.

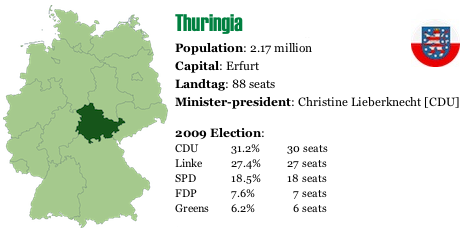

Thuringia: September 14

As in Saxony, the CDU has traditionally been the strongest force, by default, in post-reunification Germany. The CDU’s Bernhard Vogel, formerly the minister-president of Rhineland-Palatinate, served the same role for Thuringia between 1992 and 2003. His successor, Dieter Althaus, served between 2003 and 2009, when he led the CDU to a loss of 15 seats, forcing it into coalition with the SPD. It’s not been the most harmonious government in the last five years, however.

As in both Saxony and Brandenburg, there’s a 5% threshold for winning seats to the Landtag, and the FDP is also in danger of losing its seats. The latest INSA survey from early August gives the CDU 34%, the Left 26%, the SPD 19%, the Greens 6%, the AfD 5% and the FDP just 4%.

With no party is set to win an absolute majority, the SPD will be left to determine the next government — either another middle-road government as the CDU’s junior partner or a turn to the Left (and possibly, the Greens as well). That would make Ramelow the country’s first Left ministerpräsident, and even more importantly, provide another precedent for a potential ‘red-red-green’ coalition in national politics. It’s worth noting that, even today, in the era of Merkel’s political dominance, the SPD, Left and Greens still form a slight majority in the Bundestag.

Ramelow has been a member of the Thuringian assembly since 1999, and he’s led the Left’s caucus in the assembly since 2001, so he’s a known quality, and he’s generally powered the Left into the second-strongest party in the state — to nearly 27% of the vote in the last election, a total that Ramelow hopes to top this time around. If he narrowly missed out on winning the premiership in 2009, the current election represents his last — and the Left’s best chance — at winning power. Ramelow won a court case last year in which he successfully fought German state surveillance into his political activities, and the Left has generally become less controversial over time as it’s moderated to include disaffected SPD officials in addition to its eastern core.

But it’s still a far different fate than merely continuing the current government under the CDU’s Christine Lieberknecht.

Bottom line: As the SPD tiptoes toward considering a national alliance with the Left, local and state coalitions have become more popular. But in Thuringia, it would require that the SPD takes the junior role. If the SPD does turn to the Left, it would make Ramelow the Left’s first and only minister-president, marking a sharp left turn for Thuringia’s government.