The United States isn’t the only country in the world hurtling toward a governance crisis this week.![]()

On Saturday, former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi pulled the five center-right members out of the governing coalition that’s been headed for five months by center-left prime minister Enrico Letta (pictured above, right) and called for snap elections. The Italian stock market plunged this morning, Italian debt yields are already slightly rising and, once again, Italy, despite the best efforts of president Giorgio Napolitano, may well be headed to its second set of elections within 12 months — a move that would introduce new uncertainty within the eurozone at a time when most European leaders and global investors hoped the worst of the European economic crisis was over.

The big question is whether this truly marks the onset of another government collapse in Italy’s long-running political drama. There’s reason to believe it’s more the last gasp of a disgraced former leader than a principled stand over competing visions for Italy’s budget and finances. Berlusconi will shortly begin a year-long prison sentence (though due to his age, it’s likely to be house arrest or community service) after exhausting his appeals of a tax fraud conviction stemming from his leadership of Mediaset. Berlusconi also faces appeals for conviction on charges of paying for sex with a minor and abuse of power in trying to cover it up that carries a seven-year prison sentence. Most immediately, however, Berlusconi is angry that Italy’s parliament hasn’t lined up to lift a public service ban that now applies to Berlusconi in the wake of his tax fraud conviction. At age 77 and 19 years after he first become Italy’s prime minister, Berlusconi faces the indignity of being stripped of his senatorial seat in October and being banned from the next election.

It’s never smart to bet against Berlusconi, whose wealth, media power and longevity in power makes him easily the most influential political leader in Italy — even today. In the February parliamentary elections, he boosted the Italian center-right (centrodestra) coalition to within a razor-thin margin of defeating the center-left (centrosinistra) coalition. But it’s not hard to see the latest political moment as Berlusconi lashing out in order to pull one last rabbit out of his magical political hat. Earlier today, Berlusconi accused Napolitano of colluding with Italian judges against him.

If Berlusconi can bluster his way to early elections, he could potentially bring about a new parliament, especially with the center-left fractured ahead of a leadership election on December 8. But that’s a big ‘if,’ and as Monday closed in Rome, there were signs that members within Berlusconi’s ranks were none too pleased with his strategy.

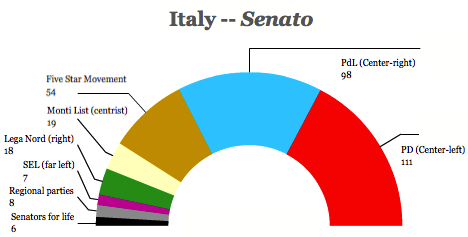

The center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), which narrowly won February’s parliamentary elections, holds a strong majority in the Camera dei Deputati (House of Deputies) due to election laws that provide a ‘winner’s bonus’ to the party with the most support. It’s more chaotic in the Senato (the Senate), where seats are allocated on a state-by-state basis and where no party holds an absolute majority:

Realistically, that means no government can form without the Democrats, but that the Democrats alone cannot govern without allies in the Senate. When the protest, anti-austerity Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) refused to enter a governing coalition with the Democrats, the only potential coalition was a ‘grand coalition’ between the Democrats and Berlusconi’s Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom). Berlusconi has since rechristened the PdL as Forza Italia, the name of his original center-right political party in the 1990s.

So Berlusconi assented and Letta formed the government in May after a gridlocked spring when Italy had merely a caretaker government and its parliament failed numerous times to elect a new president — it ultimately reelected Napolitano to another seven-year term. For good measure, five regional senators and 19 centrist senators from the coalition headed by Mario Monti (the former pro-reform, technocratic prime minister between 2011 and 2013) joined the coalition. That gave Letta a coalition in the upper house that includes 233 out of the 315 elected senators.

But the coalition has never been incredibly stable, as you might expect. On the surface, the current crisis revolves around the budget (just like in the United States) — Letta and the Democrats want to allow Italy’s VAT to rise from 21% to 22%, and Berlusconi prefers to find savings within the budget to keep the VAT from rising. The failure to find those savings last Friday precipitated Berlusconi to pull the PdL’s ministers out of the government. The risk is that the budget deficit will rise above 3% of Italian GDP, violating the European Union’s fiscal compact and potentially causing a rise in Italian debt yields. Continue reading Does this week’s political crisis in Italy represent Berlusconi’s last stand?