The way the US and international media portrayed Monday evening’s meeting between US president Barack Obama and Russian president Vladimir Putin, you might think that the diplomatic maneuvering at the United Nations General Assembly over Syria’s civil war amounted to a fight-to-the-finish struggle for the two countries, both of which are permanent members on the UN Security Council.

![]()

![]()

![]()

But that’s just not true because the stakes in Syria for the United States are far, far lower. It is tempting to view every disagreement between the United States and Russia as a zero-sum game, with a clear winner and a clear loser, but that’s false.

Here’s why.

Why Syria matters so much to Putin

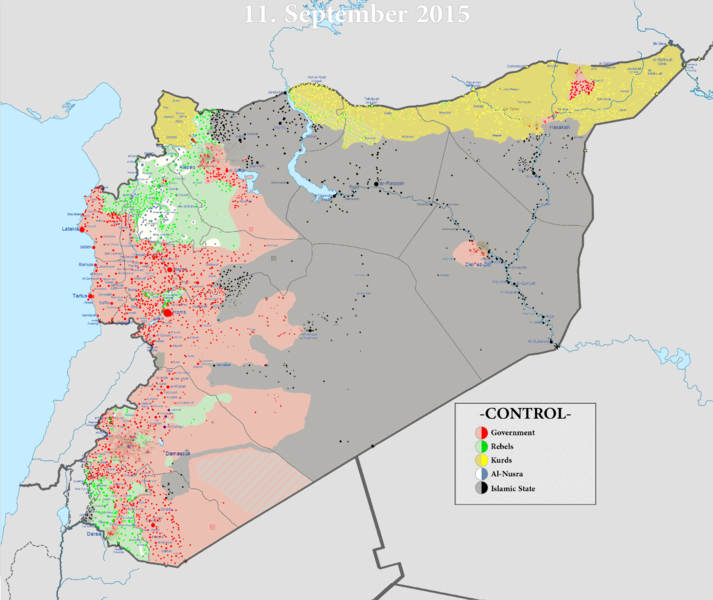

Consider how important Syria and, in particular, Bashar al-Assad, is to Russia. Assad, these days, doesn’t control much of Syria’s territory, but he does retain power throughout many of the coastal cities where most of Syria’s weary population still resides. That’s important to Moscow because the Syrian coast hosts the only warm-water port for the Russian navy at Tartus.

But it’s so much more.

While the United States continues to project influence on a global basis and while China has expanded its regional reach into south Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and even parts of Latin America, Russia’s post-Soviet influence is more limited. The battle lines between Russia and the ‘West’ are no longer Vietnam or Afghanistan or even Poland or Hungary, it’s skirmishes within former Soviet republics like Ukraine and Georgia or fights over influence in central Asia.

* * * * *

RELATED: One chart that explains Obama-era Middle East policy

RELATED: The idea of a nuclear war with Russia is absolutely crazy

* * * * *

Syria, however, retained the strong ties with Moscow that it developed under Assad’s father Hafez in the 1970s. Outside the former Soviet republics, there is virtually no other country that you could consider anything like a Russian ‘client state,’ with the exception of Syria. That’s a big deal for a country resentful that it has gone from a truly global player — culturally, technologically, politically and economically — to regional chump with fading commodity exports, crumbling physical and social infrastructure and an economy one-tenth that of the US economy. Continue reading Why the ‘brosé summit of 2015’ was more about Russia than the United States