Polls are now open across Australia, where voters will elect all 150 members of the House of Representatives, the lower house of the Australian parliament, and a little over half of the 75 members of the Senate, the upper house.![]()

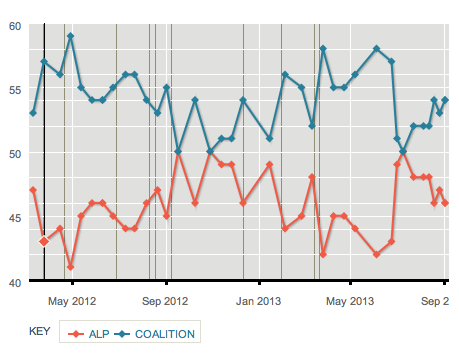

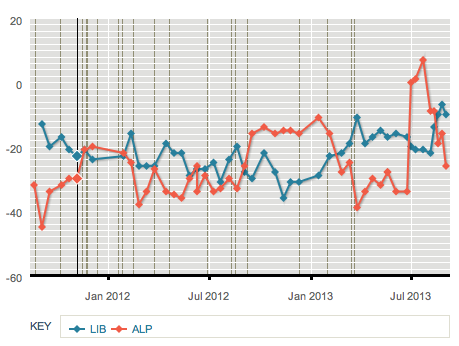

If polling surveys prove correct, prime minister Kevin Rudd (pictured above, left) and the Australian Labor Party is facing certain defeat at the hands of Tony Abbott (pictured above, right), the leader of the Liberal Party and the center-right Coalition between the Liberals and Australia’s agrarian conservative National Party.

As we wait for results to come in later today, it’s worth taking a closer look at the voting to determine just what could happen.

Polls opened at 8 am and will close at 6 pm (for those of us on the east coast, polls close on Australia’s east coast at 7 am ET and on Australia’s west coast at 9 am ET). Voting is mandatory in Australia, with a fine of around A$20 for citizens who don’t participate.

Australia elects House members in single-member constituencies, but with a preferential voting system that ranks candidates (much like Ireland’s preferential vote). Each voter casts a ballot in one of 150 electoral districts throughout Australia. But instead of just voting for one candidate, voters rank their candidate to indicate preferences from first to last.

The so-called ‘primary vote’ is the tally of the first preferences of all voters. If, after the primary vote is counted, no candidate wins an absolute majority, the candidate with the lowest amount of support is eliminated, and the second preferences of the voters who preferred the eliminated candidate are distributed to the remaining candidates. Candidates are eliminated, and preference are allocated, until one candidate wins more than 50% of the vote. In reality, this typically means that all third-party candidates are eliminated, and the final count comes down to a contest between the Coalition and Labor — this is referred to as the ‘two-party preferred vote.’

So imagine a race with three candidate — Kevin, Tony and Christine. Suppose that in the primary vote, Kevin wins 35%, Tony wins 45% and Christine wins 20%. Christine would be eliminated, and we would look at the second preference of all of Christine’s voters. Suppose that Christine’s voters preferred Kevin and Tony equally — when the second-preference votes are added to the existing tallies, we would see that Tony wins the election with 55% to just 45% for Kevin.

The system for determining senators is even more complex because voters elect 12 senators for each state (in a typical election, voters select just six senators for each state, but in a ‘double dissolution’ election, voters sometimes choose all 12 at once). Senate elections are conducted with the same principles of preferred voting, but within statewide multi-member districts. I’ll spare you the details, but if you’re interested in how the vote count becomes exponentially more complex, feel free to watch this primer.

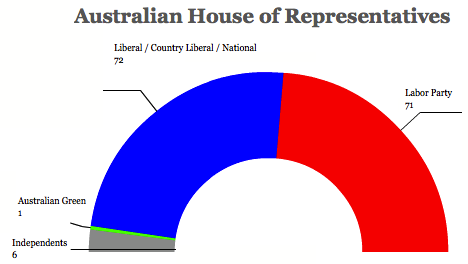

In the previous August 2010 election, neither Labor nor the Coalition won enough seats to form an absolute majority in the House — Abbott’s Coalition actually has one more MP in the House today than Rudd’s Labor (a 72-71), which means that Abbott needs to pick up just four seats to become prime minister:

Realistically, if polling data is correct, it’s not a question of whether Abbott and the Coalition will win — it’s a matter of how large Abbott’s majority will be. So without further ado, here’s a look at each of Australia’s six states and two territories and where Labor and the Coalition stands in each (for even further reading, here’s a look at the policies that Abbott’s government is likely to pursue and here’s an look at whether Labor MPs should have sacked former prime minister Julia Gillard three months ago in the hopes that Rudd could deliver an improbable victory.

Continue reading Rudd-erdämmerung 2013: An election-day guide to Australia’s national elections