The United States isn’t the only country in the world hurtling toward a governance crisis this week.![]()

On Saturday, former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi pulled the five center-right members out of the governing coalition that’s been headed for five months by center-left prime minister Enrico Letta (pictured above, right) and called for snap elections. The Italian stock market plunged this morning, Italian debt yields are already slightly rising and, once again, Italy, despite the best efforts of president Giorgio Napolitano, may well be headed to its second set of elections within 12 months — a move that would introduce new uncertainty within the eurozone at a time when most European leaders and global investors hoped the worst of the European economic crisis was over.

The big question is whether this truly marks the onset of another government collapse in Italy’s long-running political drama. There’s reason to believe it’s more the last gasp of a disgraced former leader than a principled stand over competing visions for Italy’s budget and finances. Berlusconi will shortly begin a year-long prison sentence (though due to his age, it’s likely to be house arrest or community service) after exhausting his appeals of a tax fraud conviction stemming from his leadership of Mediaset. Berlusconi also faces appeals for conviction on charges of paying for sex with a minor and abuse of power in trying to cover it up that carries a seven-year prison sentence. Most immediately, however, Berlusconi is angry that Italy’s parliament hasn’t lined up to lift a public service ban that now applies to Berlusconi in the wake of his tax fraud conviction. At age 77 and 19 years after he first become Italy’s prime minister, Berlusconi faces the indignity of being stripped of his senatorial seat in October and being banned from the next election.

It’s never smart to bet against Berlusconi, whose wealth, media power and longevity in power makes him easily the most influential political leader in Italy — even today. In the February parliamentary elections, he boosted the Italian center-right (centrodestra) coalition to within a razor-thin margin of defeating the center-left (centrosinistra) coalition. But it’s not hard to see the latest political moment as Berlusconi lashing out in order to pull one last rabbit out of his magical political hat. Earlier today, Berlusconi accused Napolitano of colluding with Italian judges against him.

If Berlusconi can bluster his way to early elections, he could potentially bring about a new parliament, especially with the center-left fractured ahead of a leadership election on December 8. But that’s a big ‘if,’ and as Monday closed in Rome, there were signs that members within Berlusconi’s ranks were none too pleased with his strategy.

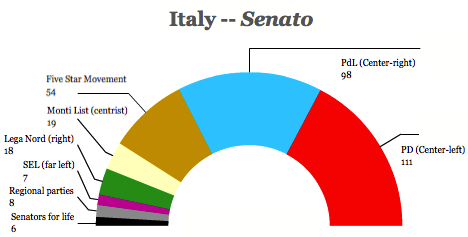

The center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), which narrowly won February’s parliamentary elections, holds a strong majority in the Camera dei Deputati (House of Deputies) due to election laws that provide a ‘winner’s bonus’ to the party with the most support. It’s more chaotic in the Senato (the Senate), where seats are allocated on a state-by-state basis and where no party holds an absolute majority:

Realistically, that means no government can form without the Democrats, but that the Democrats alone cannot govern without allies in the Senate. When the protest, anti-austerity Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) refused to enter a governing coalition with the Democrats, the only potential coalition was a ‘grand coalition’ between the Democrats and Berlusconi’s Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom). Berlusconi has since rechristened the PdL as Forza Italia, the name of his original center-right political party in the 1990s.

So Berlusconi assented and Letta formed the government in May after a gridlocked spring when Italy had merely a caretaker government and its parliament failed numerous times to elect a new president — it ultimately reelected Napolitano to another seven-year term. For good measure, five regional senators and 19 centrist senators from the coalition headed by Mario Monti (the former pro-reform, technocratic prime minister between 2011 and 2013) joined the coalition. That gave Letta a coalition in the upper house that includes 233 out of the 315 elected senators.

But the coalition has never been incredibly stable, as you might expect. On the surface, the current crisis revolves around the budget (just like in the United States) — Letta and the Democrats want to allow Italy’s VAT to rise from 21% to 22%, and Berlusconi prefers to find savings within the budget to keep the VAT from rising. The failure to find those savings last Friday precipitated Berlusconi to pull the PdL’s ministers out of the government. The risk is that the budget deficit will rise above 3% of Italian GDP, violating the European Union’s fiscal compact and potentially causing a rise in Italian debt yields.

The Letta government hasn’t particularly found the political will to implement widespread reforms and it hasn’t made much progress on its other priority — a new election law for Italy. Despite the fact that no one likes Italy’s election law, there’s no consensus about how to change it, either, so a new election would largely be a three-way split among the center-right, the center-left and the Five Star Movement. A recent IPSOS poll shows that the PdL would win 27.7% and the broader centrodestra coalition 34.4%, while the PD would win 29.4% and the centrosinistra 34.2% (virtually tied), with the Five Star Movement in strong third place with 21% and Monti’s centrists holding onto 7%.

After discussions with Napolitano over the weekend, Letta will hold a vote of no confidence on Wednesday. If he loses, his government will resign and Italy will go back to the drawing board. Though Napolitano would prefer to bring together a new coalition under Letta or another figure, the fall of Letta’s government could ultimately lead to fresh elections.

But another path now looks increasingly likely — Letta will win the vote of confidence with the support of renegade PdL members who don’t agree with Berlusconi’s brinksmanship, and even most of the five ministers who resigned on Saturday have now expressed doubts about his strategy:

“I thoroughly understand his (Berlusconi’s) state of mind, but I cannot justify or share the strategy” that the ministers quit, said Health Minister Beatrice Lorenzin. Another close aide to Berlusconi, Reforms Minister Gaetano Quagliariello, said he would follow his conscience in the confidence vote.

Most notably, Angelino Alfano (pictured above, left) has begun to murmur doubts about Berlusconi’s strategy, gently cautioning that the extremist positions of the new Forza Italia are alien to Italy’s values. Historically a loyal Berlusconi lieutenant, Alfano has served as deputy prime minister and minister of the interior under the Letta coalition government — and if Italy goes to early elections and the center-right wins, Alfano (and not Berlusconi) will almost certainly become prime minister. Given that there’s a chance the Italian electorate will blame the center-right for the political crisis, Alfano would prefer to wait until conditions are better to return to campaign mode.

Beppe Grillo, the leader of the Five Star Movement, has been adamant that both the Italian left and the Italian right are so compromised and rotten that a coalition to prop up either would be a violation of the voters who flocked to the Five Star Movement as a protest against politics as usual in Italy. Grillo’s opinion of both mainstream parties hasn’t changed in the past five months — one of the top headlines on Grillos’ popular blog today is ‘Letta lies to the Italians’ with its own has tag — #LettaMente. So Letta won’t be able to look to the Five Star Movement for much assistance.

But the Democrats and their current allies hold 135 seats in the Senate without Berlusconi’s party. That means they need just 23 more senators to form a majority among the elected senators (and possibly just 20 senators if six additional ‘senators for life’ vote to support the Letta government).

What are the chances that Letta can convince up to two dozen moderates on the Italian right in the next 24 hours to support him? Especially given that Berlusconi is now a convicted tax fraudster who faces a ban from political office, a year’s imprisonment and the promise of more turbulence over his prostitution conviction, why should the Italian right continue to follow his leadership without criticism?

Fairly likely — but again, never count Il Cavaliere out in Italian politics.

4 thoughts on “Does this week’s political crisis in Italy represent Berlusconi’s last stand?”