Twenty-two days later, Portugal is set to return to its center-right government, capping a month of twists and turns in a political crisis that began with the resignation of Portugal’s finance minister Vítor Gaspar and, then, the resignation of foreign minister Paulo Portas over the austerity program that Gaspar had been in charge of implementing as a condition of Portugal’s €78 billion bailout. ![]()

Portugal’s prime minister Pedro Passos Coelho (pictured above) reached a deal over a week ago to continue the center-right government led by prime minister and his Partido Social Democrata (PSD, Social Democratic Party) in coalition with the more socially conservative party Portas leads, the Centro Democrático e Social – Partido Popular (CDS-PP, Democratic and Social Center — People’s Party), soothing the mercurial Portas by appointing him deputy prime minister and giving him additional input over future bailout discussions and the course of Portuguese economic policy.

But Portugal’s president Aníbal Cavaco Silva, formerly a PSD prime minister from 1985 to 1995, and himself often the subject of Portas’s barbed criticism, refused to approve the deal, instead asking the two parties to bring the opposition center-left Partido Socialista (PS, Socialist Party) into government for a ‘grand coalition’ that would govern through June 2014, the end of the current bailout program.

Read more background here.

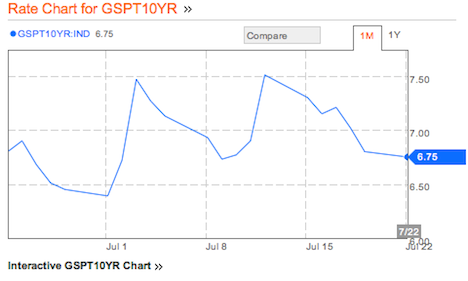

Despite talks over the past week, the three parties have failed to come to an agreement, and Cavaco Silva will now approve the government, a move that’s already pushing down Portugal’s 10-year bond yield:

Obviously, the Socialists would never join a government when they lead polls by nearly 10 points, despite the fact that it was the decision by Socialist prime minister José Sócrates to seek a bailout that led to snap elections in June 2011 that brought Passos Coehlo and Gaspar to power.

The challenge for Passos Coehlo is now three-fold:

- Though the government’s new finance minister Maria Luís Albuquerque has indicated she will follow the same path as Gaspar — that continuity is what initially caused Portas to resign in a huff earlier this month — she will face a challenging 12 months in bringing Portugal’s budget deficit toward a target of 5.5% of GDP while the economy continues to contract. She will attempt to do so without the international goodwill that Gaspar had developed over the past two years and with Portas now fully empowered to make mischief in discussions with the European and IMF officials, who had already loosened last year’s budget deficit target and are expected to agree to further adjustments to Portugal’s targets this year. Passos Coehlo has already taken pains earlier today to emphasize that Portas’s role will not compromise any of Albuquerque’s powers as finance minister.

- Cavaco Silva’s ill-advised intervention was calculated to give Portugal as stable a government as possible between now and June 2014. If Passos Coehlo’s less ambitious center-right government falls in the meanwhile — because the economy gets worse or if Portas has a bad day or whatever — it will plunge the country into uncertain snap elections at an even more sensitive time. Polls show that though the Socialists would win an election held today, Portugal’s two far-left parties would also make gains. That could possibly result in a hung parliament, which would bring about the kind of political instability that’s plagued Italy and Greece over the past year. That kind of political crisis, in turn, could reignite yet another round of eurozone-wide hand-wringing.

- Finally, there’s the matter of Portugal’s still-crumbling economy (estimated to contract another 3% this year) and the fact that Portugal already had underlying low-growth problems in the 1990s and the 2000s. Despite Gaspar’s real progress at cutting the country’s budget and raising taxes, Portugal’s public debt has increased since the bailout began, and there’s no clear indication of how Portugal’s economy will be truly competitive anytime soon. That means that Portugal is increasingly likely to require either another bailout in mid-2014 or, more likely in the long run, some form of debt relief. So even if Cavaco Silva and Passos Coehlo successfully steer the country through the next 12 months without a political crisis, there’s no escaping the fact that Portugal’s economic mess will still be driving the political conversation at the time of the next election, whether it comes in 2014 or 2015, and there’s no guarantee that the conversation won’t shift to more radical terrain at that point.

2 thoughts on “Portugal is set for a center-right government”