The People’s Republic of China doesn’t do government shutdowns.

Neither does India, the world’s largest democracy. Neither does Russia nor Japan nor the European Union.

The crisis that the United States faces over the next month — the nearly certain federal government shutdown set to begin on Tuesday and the US government’s potential sovereign default if the US Congress fails to raise the debt ceiling — is almost completely foreign to the rest of the world.

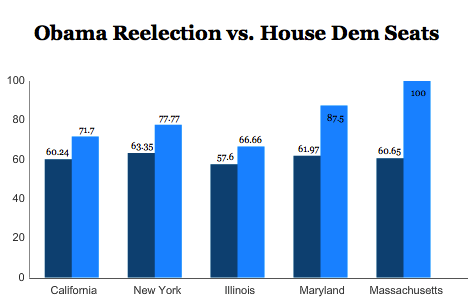

The vocabulary of the government budget crises that have sprung from divided government during the presidential administration of Barack Obama — from ‘sequester’ to ‘fiscal cliff’ to ‘supercommittee’ — is not only new to American politics, it’s a vocabulary that exists solely to describe phenomena exclusive to American politics. As the Republican Party seems ready to force a budgetary crisis over the landmark health care reform law that was passed by Congress in 2010 and arguably endorsed by the American electorate when they reelected Obama last November over Republican candidate Mitt Romney, the rest of world has been left scrambling to understand the crisis, mostly because the concept of a government shutdown (or a debt ceiling — more on that below) is such an alien affair.

If, for example, British prime minister David Cameron loses a vote on the United Kingdom’s budget, it’s considered the defeat of a ‘supply bill’ (i.e., one that involves government spending), and a loss of supply would precipitate his government’s resignation. If Italian prime minister Enrico Letta loses a vote of no confidence in the Italian parliament later this week, his government would also most likely resign. In some cases, if cooler heads prevail, their governments might form anew (such as the Portuguese government’s reformation earlier this summer following its own crisis over budget austerity). Otherwise, the country would hold new elections, as will happen later this month in Luxembourg after the government of longtime prime minister Jean-Claude Juncker fell over a secret service scandal.

So to the extent that a government falls, in most parliamentary systems, the voters then elect a government, or a group of parties that then must form a government, and that government must pass a budget and, well, govern. Often, in European and other parliamentary systems, the typically ceremonial head of state plays a real role in pushing parties together to stable government. Think of the role that Italian president Giorgio Napolitano played in bringing together both Letta’s government and the prior technocratic government headed by Mario Monti. Or perhaps the role that the Dutch monarch played in appointing an informateur and a formateur in the Dutch cabinet formation process until the Dutch parliament stripped the monarchy of that role a few years ago.�

But wait! Belgium went 535 days without a government a few years ago, you say!

That’s right — but even in the middle of that standoff, when leaders of the relatively more leftist, poorer Walloon north and the relatively conservative, richer Flemish south couldn’t pull together a governing coalition, Flemish Christian Democrat Yves Leterme stayed on as prime minister to lead a caretaker government. The Leterme government had ministers and policies and budgets, though Leterme ultimately pushed through budgets that reduced Belgium’s budget deficit. No government workers were furloughed, as will happen starting Tuesday if congressional members don’t pass a continuing resolution to fund the US government.

To the north of the United States, Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper caused a bit of a constitutional brouhaha when he prorogued the Canadian parliament in both 2008 and 2009 on the basis of potentially political considerations. In Canadian parliamentary procedure, prorogation is something between a temporary recess and the dissolution of parliament — it’s the end of a parliamentary session, and the prime minister can prorogue parliament with the consent of Canada’s governor-general. Harper raised eyebrows among constitutional scholars when he hastily prorogued the parliament in December 2008 after the center-left Liberal Party and the progressive New Democratic Party formed a coalition with the separatist Bloc Québécois in what turned out to be a failed attempt to enact a vote of no confidence against Harper’s then-minority government.

The governor-general at the time, Michaëlle Jean, took two hours to grant the prorogation — in part to send a message that the governor-general need not rubber-stamp any prime ministerial requests for proroguing parliament in the future.

Harper again advised to prorogue the parliament from the end of December 2009 through February 2010, ostensibly to keep parliament in recess through the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, though critics argued he did so to avoid investigation into his government’s knowledge of abusive treatment of detainees in Afghanistan. Again, however, proroguing parliament didn’t shutter Canadian government offices like the US government shutdown threatens to do.

Moreover, in parliamentary systems, it’s not uncommon for a government to survive a difficult vote with the support of the loyal opposition. But in the United States, House speaker John Boehner has typically (though not always) applied the ‘majority of the majority’ rule — or the ‘Hastert’ rule, named after the Bush-era House speaker Denny Hastert. In essence, the rule provides that Boehner will bring for a vote only legislation that’s supported by a majority of the 233 Republicans in the 435-member House of Representatives, the lower congressional house (Democrats hold just 200 seats). So while there may be a majority within the House willing to avoid a shutdown, it can’t materialize without the support of a majority of the Republican caucus. That means that 117 Republicans may be able to hold the House hostage, even if 116 Republicans and all 200 Democrats want to avoid a shutdown.

Realistically, that means that anything that Boehner can pass in the House is dead on arrival in the US Senate, the upper congressional house, where Democrats hold a 54-46 advantage.

There’s simply no real analog in the world of comparative politics. Even the concept of a debt ceiling is a bit head-scratching to foreign observers — US treasury officials say that the government will face difficulties borrowing enough money to achieve the government’s obligations if it fails to lift the debt ceiling of $16.7 trillion on or before October 17.

Denmark stands virtually alone alongside the United States in having a statutory debt ceiling that requires parliamentary assent to raise the total cumulative amount of borrowing, but it hasn’t played a significant role in Danish budget politics since its enactment in 1993:

The Danish fixed nominal debt limit—legislatively outside the annual budget process—was created solely in response to an administrative reorganization among the institutions of government in Denmark and the requirements of the Danish Constitution. It was never intended to play any role in day-to-day politics.

So far, at least, raising Denmark’s debt ceiling has always been a parliamentary formality, and it was lifted from 950 billion Danish kroner to 2 trillion Danish kroner in 2010 with support from all of Denmark’s major political parties.

Contrast that to the United States, where a fight over raising the debt ceiling in summer 2011 caused a major political crisis and major economic turmoil, leading Standard & Poor’s to downgrade the US credit rating from ‘AAA’ to ‘AA+.’ The Budget Control Act, passed in early August 2011, provided that the United States would raise its debt ceiling, but institute a congressional ‘supercommittee’ to search out budget cuts. When the supercommittee failed to identify budget savings before January 2013, it triggered $1.2 trillion in ‘sequestration’ — harsh across-the-board budget cuts to both Democratic and Republican priorities that took effect earlier this year, though they were originally designed to be so severe so that they would serve as an incentive for more targeted budget adjustments.

Despite the fact of the dual crises facing the US government in October, the yield on the 10-year Treasury note has actually declined in recent weeks, indicating that while US political turmoil may spook global investors, they still (ironically) invest in Treasury notes as a safe haven:

Continue reading How the US government shutdown looks to the rest of the world →

![]()

![]()

![]()