Dylan Matthews at The Washington Post wrote impressively yesterday about the perils of presidentialism and blames the current federal government shutdown not on the individual actors in the US Congress, but on the US constitution itself. Citing the late Juan Linz, who died Tuesday (coincidentally), Matthews points to a body of comparative politics research that shows presidential systems are more likely to fall into dictatorship and chaos than parliamentary systems:

But it’s not just that [James] Madison’s system is unnecessary. It’s potentially dangerous. Scholars of comparative politics have shown that presidential systems with a separation of executive and legislative functions, like America’s, are considerably more likely to collapse into dictatorship than are parliamentary systems where the executive and legislative branches are merged. That’s because there are competing branches of government able to claim democratic legitimacy and steer the ship of state at the same time — and when they disagree profoundly, there’s no real mechanism for resolving the dispute.

But parliamentary systems come with their own challenges. Italian prime minister Enrico Letta, who won a no-confidence vote yesterday after a four-day political crisis spurred by the whimsy of a single, highly volatile opposition leader, may disagree that parliamentary systems are necessarily more stable.

Matthews is right to poke holes in the sanctity with which the US political system holds 18th century governance documents, including the US constitution and the writings of Madison and others (after all, it’s important to remember that the original constitution plunged the United States into civil war — it’s the post-1865 version that includes the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments that we use today).

We live in a 21st century world that doesn’t always fall into sync with 18th century political economy. The US constitution, whether Americans like it or not, is no longer state-of-the-art technology for constitutions and hasn’t been for decades, and the US presidential system isn’t one that many countries choose to follow these days. When the United States helped craft new political systems in Germany and Japan after World War II, they built parliamentary governments with mechanisms alien to the American system.

But in a world where a minority of one house of the legislative branch of government can shut down the US government, it’s a tall order to ask that American political elites contemplate a major constitutional adjustment — a constitutional amendment to transform the United States into a parliamentary system would require the support of two-thirds of the US House of Representatives and the US Senate and the support of three-fourths of the 50 US states.

While we’re working through thought experiments, can we can lay some of the blame on the nature of the American electoral system? Maybe the United States should elect members of Congress through some form of proportional representation (or ‘PR’) instead of a ‘first-past-the-post’ system — more technically, single-member district plurality.

Although it’s typical to think about PR as a voting system used more often in parliamentary systems, both Canada and the United Kingdom (which have parliamentary systems) use a pure ‘first-past-the-post’ system to elect members to each of their respective House of Commons, while México (which has a presidential system) uses a mixed system that relies heavily on PR to determine members of both houses of its Congress.

How first-past-the-post skews US congressional elections: the 2012 conundrum

In the United States, House members are elected in single-member districts on the basis of ‘first-past-the-post’ voting. That means that the candidate who wins the most votes in the district wins the House seat. Typically in the United States, at least, that means the winning candidate will win over 50% of the vote (or close to it) because of the cultural dominance of the two-party system. That kind of two-party dominance, by the way, is much more likely to develop under the American electoral system (first-past-the-post in single-member districts) than under PR systems. That phenomenon even has a name — Duverger’s Law — and we could spend a whole post pondering the mechanisms and effects of it.

So in the most recent November 2012 US congressional election, Democrats won 48.3% of the national vote and Republicans won 46.9% for the national vote. But Democrats won just 201 seats to 234 for Republicans — the party that won 1.7 million fewer votes nonetheless holds a fairly strong majority of seats in the House (by historical standards).

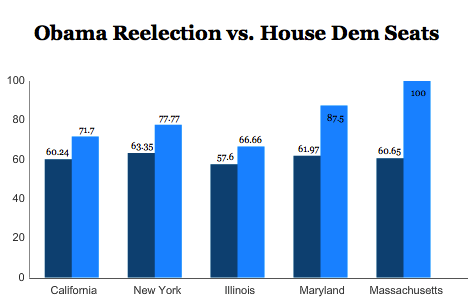

The skew is even more intense on a state-by-state basis. Here’s a chart that shows five swing states that US president Barack Obama won in his November 2012 reelection bid where Republicans simultaneously won a majority of the state’s congressional delegation — the first column is Obama’s reelection percentage and the second column is the percentage of that state’s House seats held by Republicans:

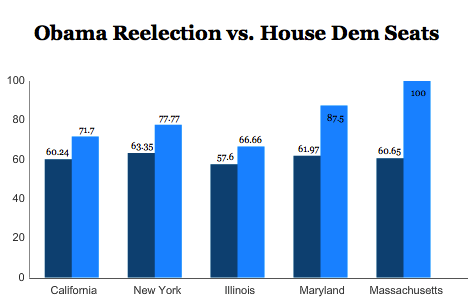

It works both ways — here’s another chart that shows five solidly Democratic states where Democrats hold an outsized advantage in the House. Again, the first column is Obama’s reelection percentage and the second column in the percentage of House seats held by Democrats:

What would proportional representation mean for the US House?

Contrast this to a PR system where seats are awarded on the basis of the party’s overall level of support. There are nearly as many varieties of PR electoral systems as there are countries on the map, but the general idea is that if a party wins 25% of the vote, it should hold 25% of the seats in the legislative body. Often, there’s an electoral hurdle — so a party would have to win 4% of the total vote in order to win any seats in the legislative body. Continue reading Don’t blame the constitution for the shutdown — blame single-member plurality districts! →

![]()