It’s far from scientific, but less than 24 hours after Republicans appeared to defeat US president Barack Obama in midterm congressional and gubernatorial elections, Russian president Vladimir Putin defeated him to the top spot on Forbes‘s 72 Most Powerful People in the World.![]()

![]()

The rankings don’t really mean that much in the grand scheme of things, of course.

The Forbes rationale?

We took some heat last year when we named the Russian President as the most powerful man in the world, but after a year when Putin annexed Crimea, staged a proxy war in the Ukraine and inked a deal to build a more than $70 billion gas pipeline with China (the planet’s largest construction project) our choice simply seems prescient. Russia looks more and more like an energy-rich, nuclear-tipped rogue state with an undisputed, unpredictable and unaccountable head unconstrained by world opinion in pursuit of its goals.

Hard to argue with that, I guess.

But the rankings represent a nice snapshot of what the US (and even international) media mainstream believe to be the hierarchy of global power. Though I’m not sure why Mitch McConnell, soon to become the U.S. senate majority leader, isn’t on the list.

So who else placed in the sphere of world politics this year?

- Obama ranked at No. 2 (From the Forbes mystics: ‘One word sums up his second place finish: caution. He has the power but has been too cautious to fully exercise it.’).

- Chinese president Xi Jinping, who took office in late 2012 and early 2013, ranked at No. 3. (Tough break for the leader of the world’s most populous country!)

- Pope Francis, ranked at No. 4, even though Argentina lost this year’s World Cup finals to Germany.

- Angela Merkel, ranked at No. 5, third-term chancellor of Germany and the queen of the European Union.

- Janet Yellen, ranked at No. 6, the chair of the US Federal Reserve.

- Mario Draghi, ranked at No. 8, the president of the European Central Bank.

- David Cameron, ranked (appropriately enough) at No. 10, the Conservative prime minister of the United Kingdom, who faces a tough reelection battle in May 2015.

- Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz Al Saud, No. 11, the king of Saudi Arabia.

- Li Keqiang, No. 13, China’s premier.

- Narendra Modi, No. 15, India’s wildly popular new prime minister.

- François Hollande, No. 17, France’s wildly unpopular president.

- Ali Khamenei, No. 19, Iran’s supreme leader, especially as Iranian nuclear talks come to a crucial deadline this month.

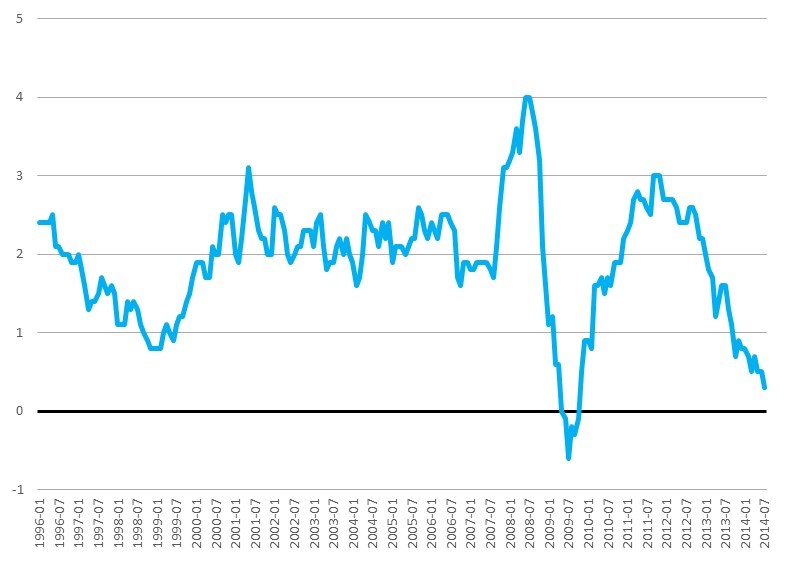

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much