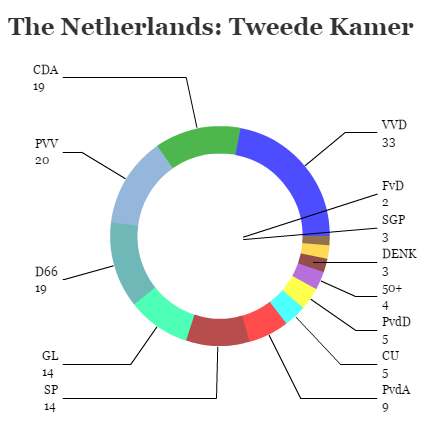

One of the growing myths of yesterday’s poor showing for Geert Wilders and the is that, somehow, the Dutch electoral system is somehow responsible for Wilders’s poor showing. ![]()

Consider this paragraph from The Economist that cautions not to extrapolate too much from Wilders’s humbling collapse to just 13% support (good enough, in the current fragmented political context, for second place):

Mr Trump’s win could not have happened without the peculiarities of America’s electoral college. By the same token, the fact that Mr Wilders did not win does not translate on to Ms Le Pen. The Dutch political system is open and diffuse, with over a dozen parties in parliament and low barriers for new ones to make it in. The French system is more rigid.

I’ve seen this theme increasingly on Twitter today (especially on #MAGA Twitter) — somehow as if it’s okay to disregard the Dutch election result because seats in the Tweede Kamer are awarded on the basis of proportional representation or because of the Dutch parliamentary system, as if another system would have delivered a resounding victory for Wilders and the Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV, Party for Freedom

Poppycock.

Imagine that Dutch elections were instead organized like American elections. You would see a primary on the right (much like we’ve seen recently in Italy, even though it’s more of a parliamentary system). In this hypothetical primary, Wilders would have campaigned against not only prime minister Mark Rutte, but against Christian Democratic leader Sybrand Buma and Christian Union leader Gert-Jan Segers and even Thierry Baudet, the head of a little-known group, the Forum voor Democratie (FvD, Forum for Democracy), a small right-wing populist and eurosceptic group that managed to win 1.8% of the national vote yesterday. If you extrapolate the results — that’s a little tricky because the Dutch voted for parties, not for personalities — it’s clear that right-leaning voters far preferred Rutte to Wilders.

That would have been true in 2012, by the way, and it would have been true in 2010 (the high-water mark for Wilders and the PVV). An American-style ‘primary’ in 2006? Former Christian Democratic prime minister Jan Peter Balkenende would have easily defeated both Rutte and Wilders. In a presidential-style ‘general election,’ Rutte would have faced off, perhaps, against Alexander Pechtold, the leader of the left-liberal Democraten 66 (D66, Democrats 66), with Wilders standing on the sidelines stewing over Islam or running a doomed third-party challenge. (Though of course sore-loser laws in the United States would have effectively prevented Wilders from running both for the Republican nomination and a third-party candidacy).

Imagine, too, a world where Dutch elections used the French system. Rutte and Wilders, as the leaders of the two parties with the largest number of votes in the 2017 election (again, it’s tricky to conflate votes for parties and votes for individuals) would presumably face one another in a runoff.

But it’s hard to see where Wilders would have picked up votes, much beyond the populist 50PLUS party or the FvD. That’s clear enough from the 65% (or so) of the Dutch electorate that supported moderate parties of both the left and the right that are generally pro-Europe and tolerant (if not always enthusiastic) of immigrants. Rutte, I’d be willing to wager, would win a French-style runoff by the same margin that centrist Emmanuel Macron currently enjoys against populist Marine Le Pen in polls forecasting the May presidential runoff in France.

Finally, consider the United Kingdom, where each member of parliament is elected in a single-member constituency by first-past-the-post voting.

There’s a reason that third parties fare so poorly in FPTP systems — they are unfairly disadvantaged.

See the map above from the 388 municipalities of The Netherlands. That sea of dark blue? It’s the wave of municipalities where Rutte’s governing Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) would have won on a FPTP basis. In a world where the Tweede Kamer was a 388-member parliament, the VVD would easily dominate it, followed (not particularly closely) in second place by the Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA, Christian Democratic Appeal), represented above in dark green.

By my count, the PVV won first place across just 23 municipalities. That compares with 13 municipalities where the Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij (SGP, Reformed Political Party) won the highest number of votes (see in orange above) — a party that wants to run the country on ‘biblical principles’ and Calvinist orthodoxy!

The system — in this case at least — had no bearing.

Wilders has no one to blame but himself and his party’s vague and divisive message. It simply didn’t break through to many Dutch voters, and that lack of enthusiasm would have manifested itself in any number of electoral systems.