It’s entirely possible that September 2016 marks the worst month of German chancellor Angela Merkel’s career.![]()

![]()

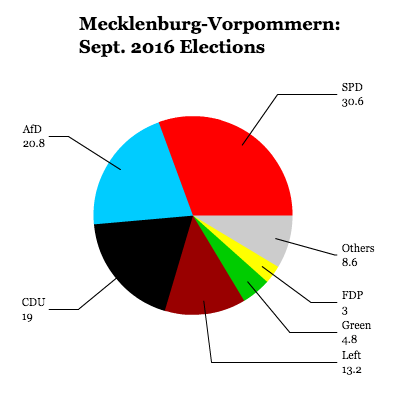

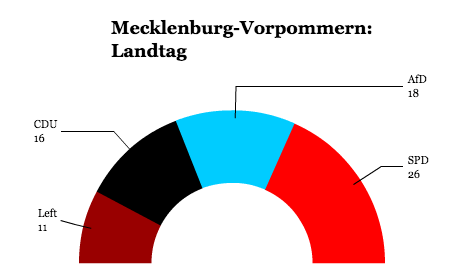

Merkel’s center-right party, the Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU, Christian Democratic Union) fell to third place in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, a relatively low-population state of just 1.6 million that sprawls along the northern edge of what used to be East Germany. While the center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) has been traditionally stronger there in elections since reunification, two factors made the CDU’s loss particularly embarrassing. The first is that it’s the state that Merkel has represented since her first election in 1990 shorly after German reunification. The second, and more ominous, is that the CDU fell behind the eurosceptic, anti-refugee Alternative für Deutschland (Afd, Alternative for Germany), a relatively new party founded in 2013 that today holds seats in 10 of Germany’s 16 state assemblies and that, according to recent polls, will easily win seats in the Bundestag in next September’s federal elections.

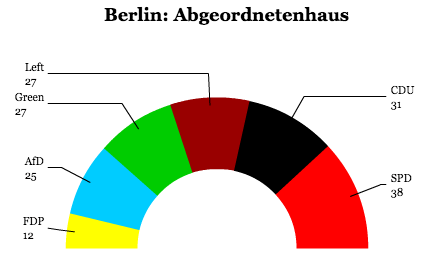

Two weeks later, on September 18, Merkel’s CDU also suffered losses in Berlin’s state election. As left-wing parties have long dominated Berlin’s politics, and the SPD placed first and Germany’s Die Linke (the Left) and Die Grünen (the Greens) placed third and fourth behind the CDU. But even in Berlin, the AfD still won 14.2% of the vote.

Taken together, the state election results forced a mea culpa from Merkel on Monday. The chancellor, who is expected (though by no means certain) to seek a fourth consecutive term next year, departed from the calm, steely confidence that since last summer has characterized her commitment to accept and integrate over a million Syrian refugees within Germany’s borders. Merkel admitted, however, that she would, if possible, rewind the clock to better prepare her country and her government for the challenge of admitting so many new migrants, and she admitted lapses in her administration’s communications. With the AfD showing no signs of abating, it’s clear that its attacks on Merkel’s open-door policy are working. Merkel’s statement earlier this week admitted that her policies have not unfolded as smoothly as she’d hoped.

* * * * *

RELATED: Can Hillary Clinton become America’s Mutti?

* * * * *

Indeed, German polls are starting to show that voters are souring on Merkel and her approach to migration, so much that in one poll in August for Bild, a majority of voters no longer support a fourth term for Merkel. All of which has led to hand-wringing both in Germany and abroad that Merkel’s days are numbered.

Don’t believe it.

Merkel well understands the risks of staying in power too long. She had a front-row seat to the hubristic and disastrous decision of her mentor, Helmut Kohl, to seek a fifth consecutive term in 1998. She may decide that, after three terms and 12 years in power, 2017 is indeed the best time for her to step aside and hand over the CDU’s leadership to a fresher face.

But certainly, if Merkel wants a fourth term, it’s hard to see how her party or her country will deny it. The CDU, together with its Bavarian sister party, the Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern (CSU, Christian Social Union), continues to hold a wide lead, typically in double digits, against the SPD, which has served as Merkel’s junior partner twice in Germany’s Große Koalition, a grand coalition that unites the center-left and the center-right. In particular, the typically cautious Merkel has used Große Koalition politics to project herself as Germany’s great moderate, a prudent fiscal steward who’s also willing to compromise by introducing the country’s first minimum wage and phasing out nuclear energy.

While there’s routine grumbling within Merkel’s party and especially within the CSU about her refugee policy, it’s unthinkable that she’ll be pushed out internally. Her two most likely successors, defence minister Ursula Von der Leyen and interior minister Thomas de Maizière, are fierce Merkel loyalists. Julia Klöckner is a rising star, but she failed to win her own state election in Rhineland-Palatinate in March, so she remains too inexperienced, for now, to become chancellor. Another rising star is 36-year-old Jens Spahn, a pugnacious nationalist who has been willing to take a harder line on migration. Still, it’s hard to imagine Germany’s Christian Democrats embracing an openly gay leader when they’ve refused, virtually alone among western European countries, to adopt LGBT marriage equality. Bavaria’s state premier Horst Seehofer is perhaps the most vocal of Merkel’s critics, but he lacks the national profile or charisma to succeed her. Finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble is beloved by the grassroots, and he always believed he (and not Merkel) deserved to follow in Kohl’s footsteps. But at age 74, he may have an eye more for Germany’s ceremonial presidency.

No other figure in Germany today can play the kind of hand that Merkel holds. Indeed, looking across the European Union, who wouldn’t envy her position? British prime minister Theresa May faces the prospect of a stillborn premiership if she cannot successfully navigate Brexit. French president François Hollande’s likely reelection bid may fail so spectacularly that he may not even make it into next May’s runoff. Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi’s career could be felled this autumn by a high-stakes referendum on constitutional reform. None of Spain’s political leaders can even form a government. All things considered, Merkel remains the EU’s lynchpin of stability (and the world may well look to her as the de facto leader of the NATO alliance if Donald Trump wins the American presidency in November).

So what if the AfD wins 10% of the vote next September? So what if it wins 15%?

Just as Nigel Farage’s United Kingdom Independence Party stole more votes from Labour than from the Conservatives in northern England, the AfD doesn’t pull votes solely from the CDU, but from the SPD and Die Linke too, especially in the former East. In Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, where the AfD won 20.8% of the vote on September 4, the CDU saw its support drop by 4.1% from the prior state election in 2011. But the SPD suffered a swing of 5.1%, and Die Linke suffered a swing of 5.2%. The AfD’s rise isn’t solely the CDU’s loss.

More fundamentally, however, given Germany’s unique history and its consensus-driven politics, it’s still outlandish to believe that anyone resembling France’s Marine Le Pen or even Donald Trump could win enough broad-based support to take power. Moreover, by the standards of Europe’s current right-wing nationalism, the AfD is still fairly tame. After a year of internal strife that sidelined the party’s founders, 41-year-old Frauke Petry, a chemist by training who, like Merkel, was born and raised in the East, emerged as the party’s leader. Petry is arguably one of Germany’s sunniest politicians and, moreover, the AfD is still far more like the CSU than, say, the neo-Nazi Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD, National Democratic Party) that emerges from time to time.

If an election were held today, the likeliest result is still a CDU-dominated government with Merkel at the helm. With her previous allies, the Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party) once again polling above 5%, it’s not impossible that Merkel could head a ‘Jamaica’ coalition, so named for the colors of Jamaica’s flag – black (CDU), yellow (FDP) and green (Die Grünen), the latter now far more in alignment with Merkel since her turn away from nuclear power and the rise of business-friendly Greens like Winfried Kretschmann, the minister-president of Germany’s prosperous southwestern Baden-Württemberg.

Far more worrying to the CDU should be the possibility that a more charismatic SPD leader realizes there’s electoral gold to be mined in co-opting the AfD’s views on migration and presenting a more ‘respectable’ populism.

For more than a decade, the SPD has been hampered technocratic dinosaurs like Peer Steinbrück, Frank-Walter Steinmeier and its current leader, Sigmar Gabriel, who also serves as Merkel’s vice chancellor and minister for economic affairs. Gabriel will likely run in 2017 as the SPD’s chancellor candidate and, as colorless as Steinmeier and Steinbrück before him, undermined by years of cooperation with Merkel, it’s no surprise that his party is running behind the CDU by double digits.

Perhaps the party’s most charismatic leader, Hannelore Kraft, the abashedly anti-austerity and socially inclusive minister-president of Germany’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia. Unfortunately for her party, Kraft has consistently ruled out a jump to national politics and, anyway, she faces her own state elections next spring.

A radical transformation within the SPD before or, much more likely, after the next election could upend the CDU’s decade-long lock on power.

In that regard, a post-2017 revolution within the German left might resemble the Corbynite takeover of the British Labour Party or the success of Vermont senator Bernie Sanders’s full-throated democratic socialism within the Democratic Party in the United States. After all, the chief 21st century accomplishment of the German Social Democrats were the four-stage Hartz reforms of former chancellor Gerhard Schröder that made Germany’s labour markets much more competitive. Just as Labour has now abandoned the ‘third way’ politics of Tony Blair and the Democrats have abandoned the ‘triangulations’ of Bill Clinton, the SPD is long overdue.

It wouldn’t be surprising if the next successful SPD leader is willing to forge (at long last) an alliance with Die Linke after the two parties have now cooperated in several ‘red-red’ coalitions at the state level. That may include Berlin, where the CDU-SPD grand coalition no longer holds a majority in the city-state’s assembly, the Abgeordnetenhaus. Instead, the SPD leader and mayor Michael Müller may look to a ‘red-red-green’ coalition.

But also, don’t be surprised if the next successful SPD leader looks and talks a lot of like Robert Fico, Slovakia’s prime minister, an economic leftist who is also an outspoken critic of EU migration policy. At the very least, it’s easy to imagine that the SPD might be far more willing to adopt the kind of rhetoric about refugees that even Helle Thorning-Schmidt and Denmark’s leftist Social Democrats embraced (almost successfully) in last summer’s Danish elections.

For now, however, there’s still not a credible challenger to Merkel’s hegemony.

Editor’s note: The piece originally stated that Merkel grew up in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; instead, she was born in Hamberg, and she grew up primarily in Brandenburg before attending university at the University of Leipzig, which is in Saxony.