Ballot-worn and crisis-weary Greeks will go to the polls for the third time in nine months in what amounts to a fresh referendum on the country’s third European bailout.![]()

Facing a growing insurgency in his own government as he implements the terms of a new European Union-backed bailout of up to €96 billion, prime minister Alexis Tsipras will dissolve the Hellenic Parliament and call early elections for September 20 — in an autumn where Turkey, just across the Aegean Sea, is also likely to hold snap elections after the apparent failure of coalition talks.

There’s already been a disproportionately large amount of ink spilled on poor Greece in 2015. With the first disbursement of the country’s third bailout accomplished, though, there’s probably no better time for Tsipras to go to the electorate. The early expectation is that Tsipras will survive the elections and govern with a more stable and likely centrist majority. But if you’ve learned anything about Greek politics this year, it’s that you should expect the unexpected twists and turns of a country that’s struggling culturally, economically and politically to exit crisis mode.

* * * * *

RELATED: Both Greece and Turkey could be headed

for autumn snap elections

* * * * *

From anti-austerity crusade in January to a third bailout in July

Tsipras (pictured above), the leader of SYRIZA (Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς, the Coalition of the Radical Left), won election in January on a pledge to reduce the terms of Greece’s memorandum and provide relief from the effects of a half-decade of austerity imposed on Greece’s fiscal policy — all without endangering Greek membership in the eurozone. After months of talks, headed by his outspoken one-time finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, it became clear that Greece did not have the political leverage that Tsipras hoped would force a more lenient deal for his country. By the end of June, it was clear that the eurozone’s finance ministers had no appetite for extending Greece’s second bailout program without additional concessions to cut Greece’s still-bloated public sector and to reform its economy.

Tsipras then hastily called a referendum for July 5, campaigning against the latest deal on offer by the Europeans, and the ‘no’ campaign (‘oxi‘) won a stronger-than-expected victory, despite closing Greece’s banks and imposing capital controls that restricted daily ATM withdrawals, at their nadir, to just €60.

Despite the referendum, Tsipras returned to the negotiating table and ultimately accepted a proposal for the third bailout — with terms even tougher than those rejected in the July 5 referendum. Tsipras, who dismissed Varoufakis as his finance minister hours after the referendum, argued that Greece had to choose between two tough choices — austerity tied to yet another bailout program or the insolvency and financial chaos that would result from a disorderly exit from the eurozone. Tsipras essentially admitted at the time that he had no ‘plan B,’ and that his country lacked the foreign reserves to establish a new currency in the event of ‘Grexit.’

Leftist rebels increasingly split from SYRIZA over bailout

SYRIZA, until recently a loose coalition of leftists ranging from mildly anti-austerity centrists to former communists, almost immediately split over whether to accept the third bailout, in spite of the chaotic alternative. In particular, Varoufakis and then-energy minister Panagiotis Lafazanis, the leader of Left Platform (Αριστερή Πλάτφορμα), have been vocal critics of the deal, and parliamentary speaker Zoe Konstantopoulou attacked it vociferously in several key votes.

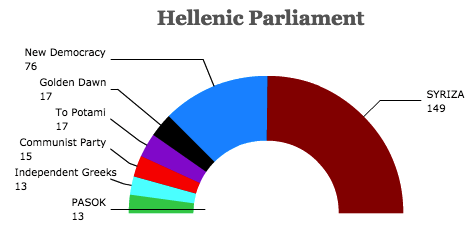

For the past month, however, Tsipras has pushed through the terms of the third bailout with dwindling support from his own party, and opposition MPs have kept his government and the bailout afloat. SYRIZA controls 149 of 300 seats in the parliament, and its junior governing partner, the nationalist right-wing and anti-austerity Independent Greeks (ANEL, Ανεξάρτητοι Έλληνες), control just 13 more seats. But by last week, support from within Tsipras’s coalition dropped to below 120.

Ultimately, Tsipras wants to call snap elections because he can’t function indefinitely with a government that refuses to deliver him a majority. By calling a fresh vote, Tsipras hopes to win a mandate for his new approach and for the new bailout program, though even Tsipras himself has grumbled that its terms will continue to retard Greek GDP growth and employment, keeping Greece stuck in its six-year economic depression.

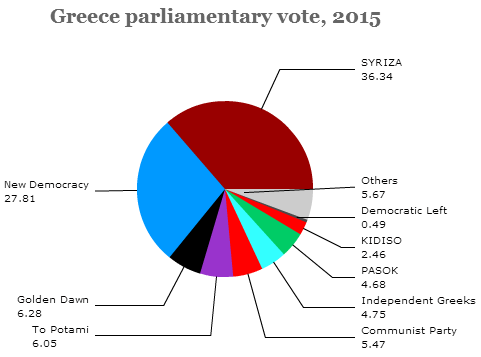

There are no reliable August polls, but surveys from the summer show that SYRIZA, under Tsipras’s leadership, still commands a massive majority of around 40% compared to just 20% for the center-right opposition, New Democracy (ND, Νέα Δημοκρατία).

But we have no polls that show what might happen if, as seems likely, Left Platform splits formally from SYRIZA. This is a crucial question because the party that wins the most votes in an election also wins a ‘bonus’ of 50 MPs. So if Left Platform steals a significant share of SYRIZA’s voters, another third party — most likely New Democracy — could win the election with a much smaller share of the vote.

Tsipras is a wily campaigner, though, and he should benefit from the fact that for the first six months of his premiership, he engaged in substantial brinksmanship in pursuit of a better deal for Greece.

He failed.

So the challenge for Varoufakis and Left Platform will be to describe how they would otherwise succeed — and how a eurozone exit would make life easier for Greece’s poor and its shrinking middle class. After all, Varoufakis and Lafazanis were key players in Tspiras’s government until July. At some point, voters will realize that the SYRIZA rebels have little more to offer than Greece’s Communist Party (KKE, Κομμουνιστικό Κόμμα Ελλάδας), which won only 5.5% in the January election. Tspiras, having followed Varoufakis’s advice, brought his country to the edge of Grexit. Tsipras will argue that Left Platform and the Greek Communists offer no solution that will keep Greece in the eurozone, and he’ll have the political scars of the last six months to prove it.

The state of Greece’s center-right and center-left opposition

Ultimately, however, Tsipras’s greatest threat may come from the right, which encompasses not just the traditional Greek right, but the center and the center-left as well. They will argue that Tsipras’s hardball negotiation tactics not only failed, but needlessly disrupted a nascent economic recovery and led to the flight of billions of deposits from Greek banks. And that’s not incorrect. But Tsipras will argue that, unlike his predecessors, conservative Antonis Samaras and leftist George Papandreou, he fought for Greek sovereignty in the face of the eurozone’s unelected officials and tried to reintroduce the democratic voice of the Greek people into the debate over Greece’s economic future.

Moreover, by calling snap elections so soon, Tsipras also hopes he can win a mandate before even more economic pain befalls voters from the additional pension cuts and an increase in Greece’s VAT required under the new bailout.

With former prime minister Antonis Samaras’s resignation after the July referendum, New Democracy has removed one of the most toxic figures in Greek politics from its leadership. But its acting leader, Vangelis Meimarakis, in office for six weeks, hardly seems prepared for the sudden challenge of unseating Tsipras. Nor does Fofi Gennimata, the leader of Greece’s once-dominant center-left party, PASOK (

Tsipras’s most credible opponent will be centrist Stavros Theodorakis, a former television reporter and commentator who founded To Potami (Το Ποτάμι, which means ‘The River’), a centrist, pro-European party, in February 2014. Theodorakis (pictured above) harshly condemned Tsipras’s decision to call a referendum over extending Greece’s bailout, but he has nevertheless supported Tsipras’s efforts to enact Greece’s new bailout since mid-July. As a more pragmatic and centrist ‘Tsipras 2.0’ is emerging, the distance between him and Theodorakis is shrinking.

If Tsipras wins, that means he will look towards To Potami as a coalition partner in his next government; until then, however, he will be fighting with Theodorakis over the same pool of centrist and center-left voters.

Though the Independent Greeks have backed Tsipras throughout the ups and downs of the last seven months, it’s not clear how such an anti-austerity party will hold onto its support after having embraced a new bailout memorandum. Its leader, defense minister Panos Kammenos, could face an uphill battle in selling the bailout deal. If ANEL collapses, however, it could be to the gain of Golden Dawn (Χρυσή Αυγή), a eurosceptic, anti-bailout, anti-immigrant and neo-fascist group that vies with To Potami for third place in the polls, typically with between 5% and 8% support.

Despite a 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’ for SYRIZA, which significantly outpolled New Democracy, the party fell just short of an outright majority in Greece’s unicameral Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων). Earlier, today, however, Tsipras

Despite a 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’ for SYRIZA, which significantly outpolled New Democracy, the party fell just short of an outright majority in Greece’s unicameral Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων). Earlier, today, however, Tsipras