Felipe González was just 41 years old when he became, in the view of many Spaniards, the most consequential prime minister to date in post-Franco Spain.![]()

![]()

![]()

Across a span of 14 years in power, González, the leader of the center-left Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), won four consecutive elections, normalized the rule of law and the traditions of democratic participation in Spain, brought the country into what was then the European Economic Community, the forerunner of today’s European Union, and shepherded Spain into NATO as a firm member of the transatlantic military and security alliance.

Today, while Spaniards take for granted many of those accomplishments as pillars of the Spanish state, González is also now remembered for the levels of corruption that sank his final government and a botched attempt to combat armed Basque nationalists.

But he’s still the first among Spain’s elder statesmen, in many ways as influential as the former king, Juan Carlos I, who abdicated in 2014 in favor of his son Felipe VI. In truth, the two are more responsible than anyone for Spain’s vibrant democracy today.

Third election a Christmas miracle?

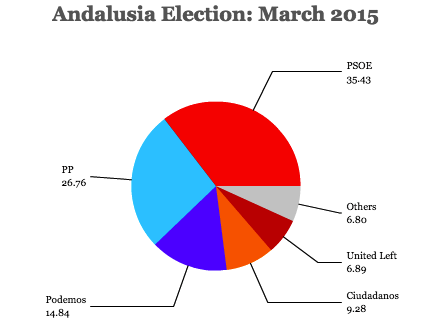

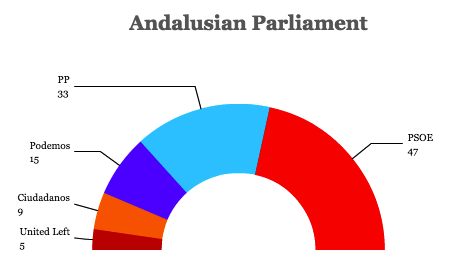

As his country enters its 10th month without a government, voters may worry that Spanish democracy has become a bit too vibrant in recent years, as a strong two-party political system has crumbled into a four-party state with myriad regionalist parties from all corners of Spain, its two-party system dissolved under the penumbra of depression-level GDP contraction and unemployment.

That’s why, after two elections, the first in December 2015 and the second in June 2016, no party can quite cobble together the necessary majority to form a government. If Spain’s party leaders cannot unlock a breakthrough by the end of October, the country will head to the polls for the third time in 13 months, possibly even on Christmas Day 2016.

González, who has doled out criticism for all of Spain’s political leaders, is one of the few PSOE figures publicly urging his party and its young leader, Pedro Sánchez, to concede its fight to deny another government under conservative prime minister Mariano Rajoy. In his view, Spain would suffer greater damage from a third general election in 13 months — as polls show that yet another snap election would result in essentially the same deadlock as the last two. In a country where turnout of 75% or more isn’t uncommon, turnout dropped from 69.7% in December to just 65.7% in June, and it could fall even lower, to 63% or worse, with another snap vote. Generally speaking, Spanish observers believe that will boost the PP, at the expense of the PSOE and Podemos, the leftist, anti-austerity movement that formed in 2014 out of the indignados movement of Spain’s masses of unemployed workers.

* * * * *

RELATED: PSOE’s incentives point to PP-Ciudadanos minority government in Spain

* * * * *

Another election in Spain would come as both Germany and France face national elections in 2017 with rising eurosceptic sentiment. It would come weeks after a make-or-break referendum on constitutional reform that’s seen as a plebiscite on Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi, and as the United Kingdom, under its new prime minister Theresa May, maneuvers to leave the European Union after its blockbuster June 2016 ‘Brexit’ vote. It could fall just days after the United States might elect businessman and reality television star Donald Trump as its next president.

So the last thing Spain’s leaders (and European and American leaders) want is another inconclusive vote and prolonged uncertainty that could threaten the slight economic growth that Spain’s generated in 2015 and 2016 and that has left the country without a government to implement a budget for the next year or provide leadership in ongoing post-Brexit debates over the European Union’s future.

Rajoy fails to win investiture vote

The latest despair comes after another failed attempt by Rajoy to retain power. Although his conservative Partido Popular (PP, the People’s Party) won the greatest number of seats in the most recent June election (indeed, a 14-seat increase from the December election), he has twice failed to win two confidence votes since the end of August, with a majority of the Chamber of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados), the lower house of the Spanish parliament, blocking Rajoy’s investiture. Continue reading Pressure builds on Sánchez as third Spanish election looms