It’s a bridge too far to say that the Turkish opposition is responsible for a decade and a half of losses to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.![]()

But there’s no doubt that his opponents certainly haven’t posed an effective brake on Erdoğan’s accelerating chokehold on Turkish democracy.

Turkish voters, according to official tallies, narrowly approved sweeping changes to the Turkish constitution on April 16 that bring far more powers to the Turkish presidency with far fewer checks and balances against the newly empowered executive.

This was always Erdoğan’s plan.

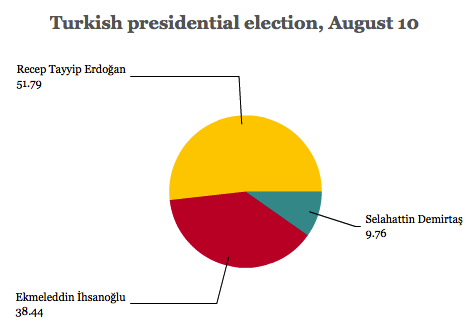

It was his plan in August 2014, when the longtime prime minister stood for (and won) the presidency, introducing a de facto presidential system in Turkey. Prime minister Binali Yıldırım essentially serves at the pleasure of the Turkish president today.

It was his plan last weekend, when he won (or possibly stole) a victory for a de jure presidential system through 18 separate constitutional amendments, many of which take effect in 2019 with a likely joint parliamentary and presidential election. Most immediately, however, Erdoğan will be able to drop the façade of presidential independence and return to lead the party that he already controls indirectly. (It’s a step that apparently won praise, almost alone among Atlantic leaders, from US president Donald Trump and Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán.)

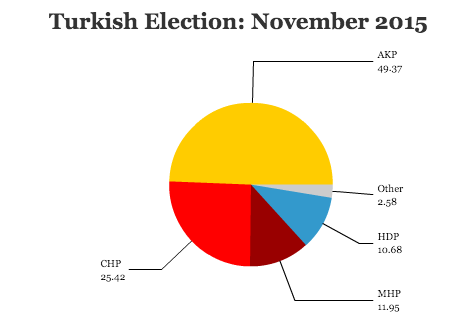

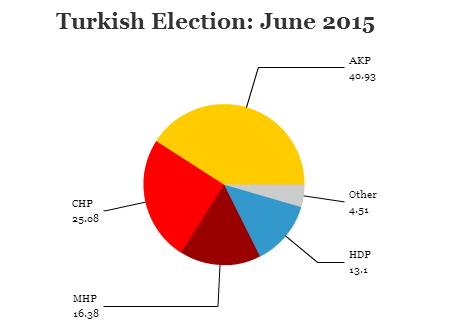

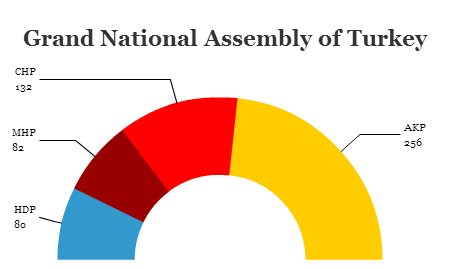

It was his plan when, after the longtime ruling Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party) failed to win an outright majority in June 2015, he plotted a crackdown on the Kurdish minority — after years of progress in integrating Kurds by relaxing restrictive and counterproductive restrictions on Kurdish language and culture — to engineer a majority win in a new round of elections five months later. Continue reading The only way to save Turkish democracy is a competent opposition