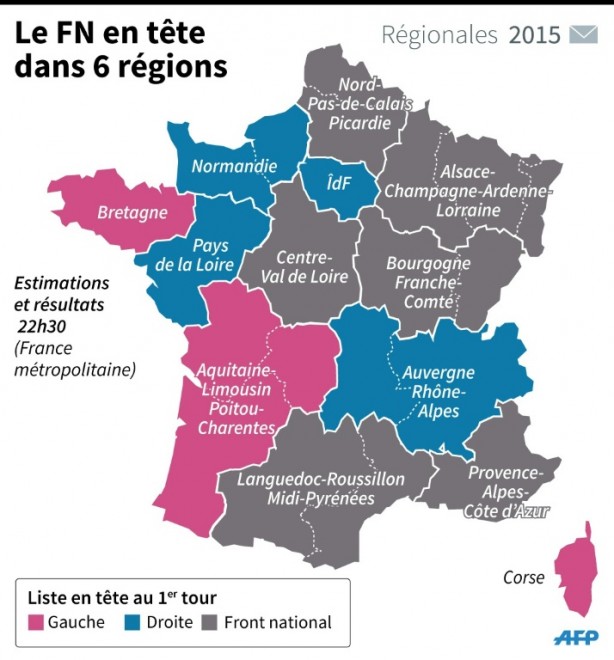

With both the mainstream left and right teaming up to defeat the far-right Front national‘s two most outspoken leaders in Sunday’s second (and final) round of regional elections, party president Marine Le Pen, in France’s far northern region, and her niece, Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, in France’s southeast, it was never likely that anyone from the Le Pen family tree would have won control of any of France’s regional councils. ![]()

Indeed, after the Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) universally withdrew from the two (of six) regions where the Front national (FN, National Front) led after the December 6 first-round results, it made a second-round victory of either Le Pen very unlikely.

Socialist unity fell short in three northeastern regions, where the Front national came far closer to winning:

- In Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, the Socialists maintained their hold on the region, but only narrowly — with 34.7% to 32.9% for the center-right Républicains (Republicans) to 32.4% for the Front national.

- In Centre-Val de Loire, again, the Socialists won 35.4% to 34.6% for the Republicans and 30.0% for the Front national.

But it was Alsace-Champagne-Ardenne-Lorraine where the Front national‘s chances of picking up a region were deemed strongest. The new region cobbles together three very different smaller regions, much to the disdain of the wealthier Alsatians, lumped into a ‘super region’ with the poorer, industrial Lorraine. (And indeed, the Front national did most poorly within the districts of the former region of Alsace, picking up larger margins in Lorraine).

Florian Philippot, one of the FN’s brightest rising stars, won the first round with 36.1% to the center-right’s 25.8%. In the second round, however, Philippot still won just 36.1% while the center-right consolidated its support (and a wide swath of the center-left and those in the electorate who didn’t bother to vote in the first round) to a whopping 48.4%, easily taking the region.

The surge in turnout among moderate voters in opposition to the Front national‘s first-round success stopped Philippot — as it did the party’s other candidates on Sunday. Still, without that shift, and a generous shift of left-wing voters to the Républicains, Philippot today might be the only Front national figure leading one of France’s 13 councils.

In contrast to the party’s self-cultivated status as an outside force with disdain for the French political elite, the 34-year-old Philippot is a graduate of the École nationale d’administration, as elite an institution as exists in France today. Since July 2012, he has been the Front national’s vice president, in charge of strategy and communication. But he’s really been the chief strategist to Marine Le Pen as she’s worked for the detoxification — or dédiabolisation — of her party, so much so that one of Le Pen’s former foreign policy advisers, Aymeric Chauprade, an MEP, left the party arguing that Philippot had created a ‘Stalinist’ environment among the party’s top guard.

There’s just one problem. For a party with a historical ambivalence to France’s gays and lesbians, Philippot is a not-quite-openly gay man. Continue reading The French far-right’s star is a not-quite-openly gay man